Prognostic and predictive value of plasma testosterone levels in patients receiving first-line chemotherapy for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: Biomarkers for metastatic castration-resistant prostatic cancer (mCRPC) are an unmet medical need. METHODS: The prognostic and predictive value for survival and response

to salvage hormonal therapy (SHT) of baseline testosterone level (TL) was analysed in a cohort of 101 mCRPC patients participating in 9 non-hormonal first-line chemotherapy phase II–III

trials. Inclusion criteria in all trials required a TL of <50 ng dl−1. RESULTS: Median age: 70 years; visceral metastases: 19.8%; median prostate-specific antigen (PSA): 50.7 ng ml−1;

median TL: 11.5 ng dl−1. Median overall survival (OS; 24.5 months) was significantly longer if baseline TL was above (High TL; _n_=52) than under (Low TL; _n_=49) the TL median value (32.7

_vs_ 22.4 months, respectively; _P_=0.0162, hazard ratio (HR)=0.6). The presence of anaemia was an unfavourable prognostic factor (median OS: 20.6 _vs_ 28.4 months; _P_=0.0025, HR=1.88

(CI95%: 1.01–3.48)). Patients presenting both anaemia and low testosterone had a worse outcome compared to those with one or none of them (median OS: 17.9 _vs_ 22.4 _vs_ 38.1 months;

_P_=0.0024). High _vs_ Low TL was associated with PSA response rate (55.6% _vs_ 21.7%) in 41 patients receiving SHT. CONCLUSION: Testosterone level under castration range was a prognostic

factor for survival mCRPC patients. The PSA response to SHT differed depending on TLs. Testosterone levels might help in treatment decision. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PROGNOSTIC

ROLE OF DOCETAXEL-INDUCED SUPPRESSION OF FREE TESTOSTERONE SERUM LEVELS IN METASTATIC PROSTATE CANCER PATIENTS Article Open access 12 August 2021 PROGNOSTIC ROLE OF THE DURATION OF RESPONSE

TO ANDROGEN DEPRIVATION THERAPY IN PATIENTS WITH METASTATIC CASTRATION RESISTANT PROSTATE CANCER TREATED WITH ENZALUTAMIDE OR ABIRATERONE ACETATE Article 18 February 2021 TIME TO CASTRATION

RESISTANCE IS A NOVEL PROGNOSTIC FACTOR OF CANCER-SPECIFIC SURVIVAL IN PATIENTS WITH NONMETASTATIC CASTRATION-RESISTANT PROSTATE CANCER Article Open access 28 September 2022 MAIN Castrate

state has been defined as a testosterone plasma level from 20 to 50 ng dl−1. Today, it is accepted by consensus that target testosterone level (TL) for androgen-deprivation therapy involving

the use of luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) agonists must be <50 ng dl−1 (1.7 nmol l−1). Docetaxel has been considered as the gold standard treatment for patients with

metastatic prostate cancer progressing under castrate levels of testosterone. In the recent years, we have contemplated the arrival of new therapeutic options, either chemotherapy (CT) with

cabazitaxel or hormone therapy with enzalutamide or abiraterone. Enzalutamide (Scher et al, 2012) and abiraterone (de Bono et al, 2011) have proven efficacy for both patients with metastatic

castration-resistant prostatic cancer (mCRPC) progressing after docetaxel and in first-line therapy for asymptomatic patients or for those with low symptoms (Ryan et al, 2013a; Prevail

trial, 2013). Cabazitaxel provided a benefit in survival for those patients progressing after docetaxel-based CT (de Bono et al, 2010). Although survival has improved, necessity of

optimisation of therapy together with some small preliminary reports of cross-resistance between abiraterone and enzalutamide (Loriot et al, 2013; Noonan et al, 2013) or abiraterone and

docetaxel (Mezynski et al, 2012) have raised the necessity of biomarkers to help the right choice of therapy for each individual patient. In patients receiving LH-RH agonist or surgical

castration, testosterone can still be detected in plasma. Baseline TL, although under the definition of castration, has been suggested to be both prognostic for survival (Morote et al, 2007)

and predictive of response to subsequent hormonal manoeuvres (Hashimoto et al, 2011). Looking to new prognostic and predictive values for survival in mCRPC, we analysed the role of baseline

TL and other potential factors (such as haemoglobin) in a cohort of patients with mCRPC. In addition, we analysed the probability of response to salvage hormone therapy (SHT) upon

progression to first-line treatment. PATIENTS AND METHODS STUDY POPULATION To have a homogeneous cohort, only patients with histologically confirmed metastatic prostate cancer (mCRPC)

participating from August 2006 until September 2012 in trials in two single institutions in Spain were included in this analysis. Patients were recruited from nine different non-hormonal

first-line CT phase II–III trials. Follow-up was until death or last contact date. All trials uniformly required, as inclusion criteria, a surgical or medical castration and confirmatory

castrate levels of testosterone (TL <50 ng dl−1). Testosterone level was determined at the screening blood analysis, using an automated immunoassay (Testosterone, ARCHITECT system I 2000

[B7K730], Abbott, Longford, Ireland; or Testosterone II, Elecsys; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) within 1 month before starting the first-line CT treatment. The protocol for collection and

measurement of TLs was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Testosterone I Architect 2006 system package insert; Abbott Diagnostics Division Lisnamuck, Longford Co.

Longford, Ireland; B7K730; or Testosterone II Immunoassay Elecsys 2010 System Product Information; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). All patients gave their informed consent in

written for blood testing. Disease progression was defined as documented osseous or soft-tissue metastatic progression (under Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) v1.1

(Eisenhauer et al, 2009), or prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression according to Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials working Group II criteria (PCWGII) (Scher et al, 2008). Overall survival

(OS) was calculated as the time from the date of study inclusion to death. Disease-free progression (DFP) was the time from the date of study inclusion to date of progression. Post-CT

progression was defined either as an objective progression according to the RECIST or as a PSA progression. The PSA progression was defined as three consecutive increases in serum PSA from

the nadir value of either at least 25% for men without PSA response (⩾50% confirmed PSA decline from baseline) or at least a 50% increase from nadir for all others. The PSA response was

defined as partial if ⩾30% reduction. Time from progression to death (TPD) was defined as the time from progression after first-line therapy to death. Patients who received hormonal

treatment after first-line progression were included in a sub-analysis to measure their PSA response to SHT and post-progression survival. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Survival times (OS, DFS, and

TPD) were analysed using a Kaplan–Meier model. For a statistical purpose, patients were stratified into two groups according to their baseline TL. Those patients with baseline TL below

median value were classified as ‘Low TL’ and as ‘High TL’ if baseline TL was above median TL value. Prostate-specific antigen was included in the model as a continuous variable as well as

categorical (median value). Other factors analysed were anaemia (defined as Hb values <12.0 g dl−1), Gleason score (>7 _vs_ ⩽7), serum level of alkaline phosphatase (>131 IU l−1),

LDH (high _vs_ normal), age (⩾65 _vs_ <65), the presence or absence of visceral metastases, hepatic metastases or dyslipidemia, and the use of statins. Univariate and multivariate

analyses were performed. Variables that achieved statistical significance in the univariate analysis were included in a stepwise COX regression model for multivariate analysis. All analyses

were performed using SAS Version 9.3. (SAS Institute Inc., SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC, USA) The guidelines for the reporting of tumour marker studies (REMARK) were followed to analyse and

present data on studied biomarkers (McShane et al, 2005). RESULTS PATIENT POPULATION One hundred and one patients with histologically confirmed mCRPC who were treated with first-line CT, in

any of the non-hormonal first-line CT phase II–III trials were included in the analysis. The great majority of patients received a docetaxel-based regimen (_n_=68) as first-line CT. Table 1

summarises the trials where patients were included in a timely basis. Median age of patients was 70.0 years (range: 41.0–89.0) and 19.8% (_n_=20) patients had visceral metastases. The median

PSA was 50.7 ng ml−1 (range: 0.04–1284.0), the median haemoglobin was 13.1 g dl−1 (range: 9.3–156.0), and the median alkaline phosphatase was 163 U l−1 (range: 39.0–1159.0). Before

development of mCPRC, all subjects received at least two hormonal treatments. These included an LH-RH analogue either alone or in combination with an antiandrogen. When an LH-RH was

administered alone at first instance, then an antiandrogen was added at progression. If the combination was used as the first approach, then the second hormonal manoeuvre was the withdrawal

of the antiandrogen. Three patients received surgical castration instead of an LH-RH analogue. Four patients (4.0%) received more than two hormonal manoeuvres before first-line CT was

introduced. These treatments corresponded to ketoconazol in three cases and diethylstilbestrol in one patient. Of these four, only one received salvage hormonal treatment after CT failure.

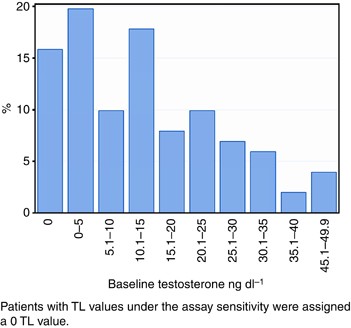

The median TL was 11.5 ng dl−1 (range: from undetectable to 49.0), with 19% of the patients having an undetectable level and 85% of the patients having less than 20 ng dl−1 of testosterone

in plasma. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of serum baseline TLs. Baseline TL was above the TL median value in 52 patients (High TL group) and under the TL median value in 49 patients (Low

TL group). No significant differences were observed in baseline characteristics between groups (Table 2). Median TL was 7.9 ng dl−1 in patients who were using statins at the time of

inclusion (_n_=18), while median TL was 11.5 ng dl−1 in those patients without statins (_n_=78). No significant correlation (_P_=0.3418) was noted between the use of statins in patients and

baseline TLs value. EFFICACY AND SURVIVAL ANALYSES At the moment of analysis (June 2013), 90 out of 101 patients had failed to first-line CT and 57 out of 101 patients had died. Median

follow-up of patients was 20.6 months (range: 8.3–29.8). Median OS was 24.5 months (CI95%: 21.8–31.7). Kaplan–Meier analysis stratified by TLs showed a median DFS higher in those patients

with High TL than with Low TL (5.7 _vs_ 4.9 months, respectively; _P_=0.001). Median OS was also longer in those patients with High TL compared with Low TL (32.7 _vs_ 22.4 months,

respectively, _P_=0.0162) (Figures 2a and b). When stratified by haemoglobin levels, OS was 28.4 _vs_ 20.6 months (No anaemia _vs_ Yes, respectively; _P_=0.0025, Figure 3a), and OS was 35.9

_vs_ 22.8 months when age was analysed (<65 _vs_ ⩾65 years old; _P_=0.0259; Figure 3b). The univariate analysis of OS demonstrated TLs (High TL _vs_ Low TL, hazard ratio (HR): 0.5; CI95%:

0.3–0.9; _P_=0.018), the presence of anaemia (Yes _vs_ No, HR: 2.4; CI95%: 1.3–4.4; _P_=0.0024), baseline PSA before CT (<51 _vs_ ⩾51 ng ml−1, HR: 0.5; CI95%: 0.3–0.8; _P_=0.0074), and

age (<65 _vs_ ⩾65, HR: 0.5; CI95%: 0.3–0.9; _P_=0.0294) to be statistically significant. Other potential prognostic factors for survival analysed did not show statistically significant

differences: Gleason (>7 _vs_ ⩽7: median OS: 22.8 _vs_ 30.3 months; HR: 1.2; CI95%: 0.7–2.2; _P_=0.4661), the presence of visceral metastasis (Yes _vs_ No: median OS: 16.5 _vs_ 26.2

months; HR: 1.3; CI95%: 0.7–2.4; _P_=0.4634), liver metastases (Yes _vs_ No: median OS: 16.5 _vs_ 26.2 months; HR: 2.0; CI95%: 0.8-4.7; _P_=0.1206), LDH (high _vs_ normal: median OS: 19.9

_vs_ 26.8 months; HR 1.5; CI95%: 0.8–2.8; _P_=0.2387), serum alkaline phosphatase levels (⩾131 _vs_ <131 IU l−1: median OS: 24.1 _vs_ 26.8 months; HR: 1.3; CI95%: 0.7–2.2; _P_=0.4249),

dyslipidemia (Yes _vs_ No: median OS: 22.4 _vs_ 26.8 months; HR: 1.1; CI95%: 0.7–1.9; _P_=0.6564), or the use of statins (Yes _vs_ No: 22.4 _vs_ 28.4 months; HR: 1.3; CI95%: 0.7–2.4;

_P_=0.4975). The multivariate analysis of OS showed TLs (High _vs_ Low testosterone) to be in the limit of significance (HR: 0.6; CI95%: 0.4–1.0; _P_=0.0689) and anaemia (Yes _vs_ No) to be

a significant factor (HR: 1.9; CI95%: 1.0–3.5; _P_=0.046). A significant interaction between both variables was demonstrated, showing that High TL was a protective factor when there was not

anaemia (HR: 0.5; CI95%: 0.3–0.8). Age (<65 _vs_ ⩾65) was not a statistically significant factor in the multivariate analysis (HR: 0.6; CI95%: 0.3–1.1; _P_=0.1075). Baseline PSA showed a

strong correlation with anaemia (_P_=0.0046) and was not included in the multivariate analysis. Since levels of haemoglobin and testosterone were significant or marginal factors for OS, we

classified patients into three groups: (patients presenting two risk factors (anaemia and Low TL), one risk factor, or without risk factors), and a Kaplan–Meier model was used to analyse the

OS. Patients presenting two factors (anaemia and Low TL) had a worse outcome compared to those with one or none of them (median OS: 17.9 _vs_ 22.4 _vs_ 38.1 months, respectively;

_P_=0.0024) (Figure 4). Post-progression survival or TPD was 16.4 months (CI95%: 12.5–25.4) in the Low LT group of patients _vs_ 23.7 months (CI95%: 16.5–35.8) in the High LT group

(_P_=0.0456) (Figure 5). In 95 out of the 101 patients, PSA response was evaluated. The percentage of responders by PSA to first-line CT was similar in both groups (High LT 57.7% (_n_=30)

_vs_ Low LT 61.2% (_n_=30)). There was not a statistically significant association between PSA response and baseline TL (_P_=0.1381). The application of a logistic model provided similar

results (Wald Chi-square _P_=0.3468). Also, PSA response rate was not associated with baseline TL in 68 of the 72 patients that received a docetaxel regimen as first-line CT (High TL 70.6%

(_n_=24) _vs_ Low TL 67.7% (_n_=23); _P_=0.5827). The PSA response was not assessed in four patients receiving a docetaxel-based CT regimen. Thus, baseline TLs were not predictive of PSA

response to first-line docetaxel. RESPONSE TO SHT AND POST-PROGRESSION SURVIVAL After first-line CT failure, 41 out of 101 (40.6%) patients received salvage hormonal treatment. As described

before, all of these patients had received at least two hormonal manoeuvres before first-line CT. Treatments received consisted of diethylstilbestrol (_n_=12, 29%), ketoconazol (_n_=11,

27%), abiraterone (_n_=9, 22%), bicalutamide or high-dose bicalutamide (_n_=7, 17%), cyproterone acetate (_n_=1, 2%), and enzalutamide (_n_=1, 2%). The PSA response to SHT was observed in

36.6% (_n_=15) of the patients, while 56.1% (_n_=23) of the patients were non-responders (SD and PD). Response data were not available in three patients. Response was observed in 21.7%

(_n_=5) of the Low TL patients _vs_ 55.6% (_n_=10) in the High TL group. A majority (73.9%; _n_=17) of the Low TL patients were non-responders, compared with 33.3% (_n_=6) in the High TL

patients (_P_=0.0196). DISCUSSION In spite of castrate levels of testosterone, all patients with metastatic prostate cancer receiving treatment with either medical or surgical castration

will finally progress, entering the so-called castrate-resistant state. Although it was thought that these patients were truly progressing independent of the activity of the androgen

receptor (AR), today it is well known that the AR is still activated in most patients. In fact, the activity of docetaxel, the present standard of care in mCRPC, can partly be explained

through its activity over the AR, blocking the process of internalisation (Darshan et al, 2011). The knowledge that the activation of the AR permits prostate cancer to escape from the

castrate levels of testosterone has conducted to the development of new therapies centred in reducing plasma and intratumoral TLs (Attard et al, 2008). Though adrenal and intratumoral _de

novo_ androgen synthesis contributes to disease progression (Locke et al, 2008; Montgomery et al, 2008), the relationship between serum androgens and intratumoral androgens remains poorly

understood. In addition, an escape of testosterone from testis may occur in some patients (Morote et al, 2007), with prognostic implications (Perachino et al, 2010). A potential role of

residual plasma androgens has been studied. Peripheral baseline androstenedione was predictive of response to ketoconazol in patients with mCRPC (Small et al, 2004). Abiraterone acetate, an

inhibitor of CYP17–20 hydroxylase, provides a further reduction in the level of plasma testosterone that correlates with PSA response in patients progressing after ketoconazol-based therapy.

The final proof of concept for abiraterone came through data from a positive phase III trial in mCRPC patients progressing after docetaxel-based CT (de Bono et al, 2011), and from a small

translational study where abiraterone was more effective for tumours with a tumour nuclear AR expression, coupled with cytoplasmic CYP17 expression (Efstathiou et al, 2012). Ryan et al

(2013b) found that baseline serum androgen (testosterone, androstenedione, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels were a validated biomarker that was prognostic for survival in

the patients treated with abiraterone after docetaxel failure in the phase III trial. The relationship of TL with PSA response by first or salvage therapies was not analysed in their study.

Our hypothesis states that plasma TL might reflect the activity of the AR. Against the use of TLs, is the fact that they may be affected by diet and circadian conditions, not well accounted

for in our study; and that there are other androgens in plasma, not only testosterone. Although, to date, no models exist that account for total androgen load, as opposed to the measurement

of the level of an individual hormone (e.g., testosterone), this could be an interesting point of further investigation, and maybe, a more accurate tool than a single hormone level. In our

study, we demonstrated that testosterone baseline levels under castration were a prognostic factor for survival before first-line CT. Several caveats should be considered when interpreting

these data, including the fact that these analyses were exploratory, with no attempt to correct for multiplicity. Testosterone was measured using commercial assays, thus, a definitive cutoff

point could not be established. Novel and more precise ultrasensitive techniques are nowadays available, although not implemented on the daily practice. Since androgen synthesis depends on

cholesterol, TL may be reduced by the use of statins. Although in our analysis the difference observed was not statistically significant, the figures are not comparable due to the small

proportion of patients that were using statins compared with those who were not. Interestingly, patients using statins had a worse OS (22.4 _vs_ 28.4 months), although this result was not

statistically significant (_P_=0.4964) and again, the interpretation is limited by the small size of the population that used these drugs. Although we could hypothesise that reducing

androgen levels with statins may drive to a lower baseline testosterone plasma levels and this could impact on patients outcome, this seems very unlikely, and patients using statins could

have a worse OS due to other reasons such as cardiovascular associated comorbidities, although these was not analysed. Finally, low TL might be a manifestation of a patient who is in poor

general health. We plan to validate our results using an external data set. It is noteworthy, in the multivariate analysis, that the presence of anaemia was a significant prognostic factor

for OS. This finding correlates with Armstrong nomograms (Armstrong et al, 2007). To be aged 65 years or more was a prognostic factor in the univariate analysis, but losses statistical

significance when considered in the multivariate analysis. Prostate-specific antigen was also a significant factor for survival but could not be included in the multivariate analysis since

it showed a strong correlation with anaemia in the Wilcoxon test. Although the Gleason score (>7 _vs_ ⩽7) and the presence of hepatic metastases (Yes _vs_ No.) showed a notable difference

in survival times in our series, this difference was not statistically significant, so we can only conclude that there was a trend towards better prognosis for survival with a lower Gleason

score and an absence of hepatic metastasis. Gleason score obtained by biopsy was allowed in our series, and this may reflect an under staging in some patients. High LDH, visceral

metastases, and hepatic metastases were present in a small number of patients (_n_=3), therefore no conclusion can be drawn up to now. In conclusion, high baseline TLs seem to be a

prognostic factor before first-line CT, and a predictive factor of improved OS among patients receiving hormonal manoeuvres after docetaxel. Moreover, AR activity can be analysed through

biopsies of the tumour, and easier ways to estimate the activity of the AR are presently lacking. The analysis of plasma TLs could, if validated in a confirmatory study, be useful for

decision of therapy. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 29 APRIL 2014 This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication _

REFERENCES * Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer ES, Yang YO, de Witt R, Tannock IF, Eisenberger M (2007) A contemporary prognostic nomogram for men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate

cancer: a TAX327 study analysis. _Clin Cancer Res_ 13: 6396–6403. Article CAS Google Scholar * Attard G, Reid AH, Yap TA, Raynaud F, Dowsett M, Settatree S, Barrett M, Parker C, Martins

V, Folkerd E, Clark J, Cooper CS, Kaye SB, Dearnaley D, Lee G, de Bono JS (2008) Phase I clinical trial of a selective inhibitor of CYP17, abiraterone acetate, confirms that

castration-resistant prostate cancer commonly remains hormone driven. _J Clin Oncol_ 26: 4563–4571. Article CAS Google Scholar * Darshan MS, Loftus MS, Thadani-Mulero M, Levy BP, Escuin

D, Zhou XK, Gjyrezi A, Chanel-Vos C, Shen R, Tagawa ST, Bander NH, Nanus DM, Giannakakou P (2011) Taxane-induced blockade to nuclear accumulation of the androgen receptor predicts clinical

responses in metastatic prostate cancer. _Cancer Res_ 71 (18): 6019–6029. Article CAS Google Scholar * de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, Fizazi K, North S, Chu L, Chi KN, Jones RJ,

Goodman OB Jr, Saad F, Staffurth JN, Mainwaring P, Harland S, Flaig TW, Hutson TE, Cheng T, Patterson H, Hainsworth JD, Ryan CJ, Sternberg CN, Ellard SL, Flechon A, Saleh M, Scholz M,

Efstathiou E, Zivi A, Bianchini D, Loriot Y, Chieffo N, Kheoh T, Haqq CM, Scher HI (2011) Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. _N Engl J Med_ 364: 1995–2005.

Article CAS Google Scholar * de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Machiels JP, Kocak I, Gravis G, Bodrogi I, Mackenzie MJ, Shen L, Roessner M, Gupta S, Sartor AO (2010) Prednisone

plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. _Lancet_ 376: 1147–1154. Article

CAS Google Scholar * Efstathiou E, Titus M, Tsavachidou D, Tzelepi V, Wen S, Hoang A, Molina A, Chieffo N, Smith LA, Karlou M, Troncoso P, Logothetis CJ (2012) Effects of abiraterone

acetate on androgen signaling in castrate-resistant prostate cancer in bone. _J Clin Oncol_ 30: 637–643. Article CAS Google Scholar * Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH,

Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised

RECIST guideline (version 1.1). _Eur J Cancer_ 45: 228–247. Article CAS Google Scholar * Hashimoto K, Masumori N, Hashimoto J, Takayanagi A, Fukuta F, Tsukamoto T (2011) Serum

testosterone level to predict the efficacy of sequential use of antiandrogens as second-line treatment following androgen deprivation monotherapy in patients with castration-resistant

prostate cancer. _Jpn J Clin Oncol_ 41: 405–410. Article Google Scholar * Locke JA, Guns ES, Lubik AA, Adomat HH, Hendy SC, Wood CA, Ettinger SL, Gleave ME, Nelson CC (2008) Androgen

levels increase by intratumoral de novo steroidogenesis during progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer. _Cancer Res_ 68: 6407–6415. Article CAS Google Scholar * Loriot Y,

Bianchini D, Ileana E, Sandhu S, Patrikidou A, Pezaro C, Albiges L, Attard G, Fizazi K, De Bono JS, Massard C (2013) Antitumour activity of abiraterone acetate against metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel and enzalutamide (MDV3100). _Ann Oncol_ 24 (7): 1807–1812. Article CAS Google Scholar * McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei

W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM (2005) Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK). _J Natl Cancer Inst_ 97 (16): 1180–1184. Article CAS Google Scholar * Mezynski

J, Pezaro C, Bianchini D, Zivi A, Sandhu S, Thompson E, Hunt J, Sheridan E, Baikady B, Sarvadikar A, Maier G, Reid AH, Mulick CA, Olmos D, Attard G, de BJ (2012) Antitumour activity of

docetaxel following treatment with the CYP17A1 inhibitor abiraterone: clinical evidence for cross-resistance? _Ann Oncol_ 23: 2943–2947. Article CAS Google Scholar * Montgomery RB,

Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, Hess DL, Kalhorn TF, Higano CS, True LD, Nelson PS (2008) Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant

tumor growth. _Cancer Res_ 68: 4447–4454. Article CAS Google Scholar * Morote J, Orsola A, Planas J, Trilla E, Raventos CX, Cecchini L, Catalan R (2007) Redefining clinically significant

castration levels in patients with prostate cancer receiving continuous androgen deprivation therapy. _J Urol_ 178: 1290–1295. Article CAS Google Scholar * Noonan KL, North S, Bitting RL,

Armstrong AJ, Ellard SL, Chi KN (2013) Clinical activity of abiraterone acetate in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after enzalutamide. _Ann Oncol_

24: 1802–1807. Article CAS Google Scholar * Perachino M, Cavalli V, Bravi F (2010) Testosterone levels in patients with metastatic prostate cancer treated with luteinizing

hormone-releasing hormone therapy: prognostic significance? _BJU Int_ 105: 648–651. Article CAS Google Scholar * Prevail Trial (2013) Medivation Press Release

http://investors.medivation.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=798880 (Last accessed on 13 December 2013). * Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, Molina A, Logothetis CJ, de SP, Fizazi K, Mainwaring

P, Piulats JM, Ng S, Carles J, Mulders PF, Basch E, Small EJ, Saad F, Schrijvers D, Van PH, Mukherjee SD, Suttmann H, Gerritsen WR, Flaig TW, George DJ, Yu EY, Efstathiou E, Pantuck A,

Winquist E, Higano CS, Taplin ME, Park Y, Kheoh T, Griffin T, Scher HI, Rathkopf DE (2013a) Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. _N Engl J Med_ 368:

138–148. Article CAS Google Scholar * Ryan CJ, Molina A, Li J, Kheoh T, Small EJ, Haqq CM, Grant RP, de Bono JS, Scher HI (2013b) Serum androgens as prognostic biomarkers in

castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from an analysis of a randomized phase III trial. _J Clin Oncol_ 31: 2791–2798. Article CAS Google Scholar * Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I,

Morris M, Sternberg CN, Carducci MA, Eisenberger MA, Higano C, Bubley GJ, Dreicer R, Petrylak D, Kantoff P, Basch E, Kelly WK, Figg WD, Small EJ, Beer TM, Wilding G, Martin A, Hussain M

(2008) Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials

Working Group. _J Clin Oncol_ 26: 1148–1159. Article Google Scholar * Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin ME, Sternberg CN, Miller K, de WR, Mulders P, Chi KN, Shore ND, Armstrong AJ, Flaig

TW, Flechon A, Mainwaring P, Fleming M, Hainsworth JD, Hirmand M, Selby B, Seely L, de Bono JS (2012) Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. _N Engl J

Med_ 367: 1187–1197. Article CAS Google Scholar * Small EJ, Halabi S, Dawson NA, Stadler WM, Rini BI, Picus J, Gable P, Torti FM, Kaplan E, Vogelzang NJ (2004) Antiandrogen withdrawal

alone or in combination with ketoconazole in androgen-independent prostate cancer patients: a phase III trial (CALGB 9583). _J Clin Oncol_ 22: 1025–1033. Article CAS Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS _ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers_: NCT00321620; NCT00744497; NCT01057810; NCT00411528; NCT00278993; NCT01308567; NCT00642018; NCT01188187; NCT00519285.

This study was performed within the Medical PhD framework of A Gómez de Liaño at the Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Medical Oncology and

Biochemistry Departments, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Mas Casanovas s/n, 08025 Barcelona, Spain, A G de Liaño, C Martin, E U Rull & J P Maroto * Medical Oncology Department,

Hospital Clinic, Carrer Villarroel 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain, O Reig & B Mellado Authors * A G de Liaño View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * O Reig View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * B Mellado View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * C Martin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * E U Rull View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * J P Maroto View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to J P Maroto. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS

ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE de Liaño, A., Reig, O., Mellado, B. _et al._ Prognostic and predictive value of plasma testosterone levels in patients receiving first-line chemotherapy for

metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. _Br J Cancer_ 110, 2201–2208 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.189 Download citation * Received: 16 December 2013 * Revised: 12 March

2014 * Accepted: 15 March 2014 * Published: 10 April 2014 * Issue Date: 29 April 2014 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.189 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with

will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * castrate-resistant prostate cancer * testosterone levels * biomarkers