Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin h1n1 influenza virus

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Influenza viruses cause annual epidemics and occasional pandemics that have claimed the lives of millions. The emergence of new strains will continue to pose challenges to public

health and the scientific communities. A prime example is the recent emergence of swine-origin H1N1 viruses that have transmitted to and spread among humans, resulting in outbreaks

internationally. Efforts to control these outbreaks and real-time monitoring of the evolution of this virus should provide us with invaluable information to direct infectious disease control

programmes and to improve understanding of the factors that determine viral pathogenicity and/or transmissibility. Access through your institution Buy or subscribe This is a preview of

subscription content, access via your institution ACCESS OPTIONS Access through your institution Subscribe to this journal Receive 51 print issues and online access $199.00 per year only

$3.90 per issue Learn more Buy this article * Purchase on SpringerLink * Instant access to full article PDF Buy now Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

ADDITIONAL ACCESS OPTIONS: * Log in * Learn about institutional subscriptions * Read our FAQs * Contact customer support SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS GENETIC AND ANTIGENIC

EVOLUTION OF H1 SWINE INFLUENZA A VIRUSES ISOLATED IN BELGIUM AND THE NETHERLANDS FROM 2014 THROUGH 2019 Article Open access 28 May 2021 NOVEL REASSORTANT SWINE H3N2 INFLUENZA A VIRUSES IN

GERMANY Article Open access 31 August 2020 POTENTIAL PANDEMIC RISK OF CIRCULATING SWINE H1N2 INFLUENZA VIRUSES Article Open access 13 June 2024 REFERENCES * Kobasa, D. et al. Aberrant innate

immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. _Nature_ 445, 319–323 (2007) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Morens, D. M., Taubenberger, J. K. &

Fauci, A. S. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. _J. Infect. Dis._ 198, 962–970 (2008) PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Taubenberger, J. K., Reid, A. H., Krafft, A. E., Bijwaard, K. E. & Fanning, T. G. Initial genetic characterization of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza

virus. _Science_ 275, 1793–1796 (1997)THIS IS AN IMPORTANT PAPER THAT DESCRIBES THE DECIPHERING OF THE GENOMIC SEQUENCE OF THE 1918 PANDEMIC INFLUENZA VIRUS. CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Reid, A. H., Fanning, T. G., Hultin, J. V. & Taubenberger, J. K. Origin and evolution of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus hemagglutinin gene. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 96, 1651–1656

(1999) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Neumann, G. et al. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNA. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 96, 9345–9350 (1999)THIS PAPER

DESCRIBES THE ARTIFICIAL GENERATION OF INFLUENZA VIRUSES, A BREAKTHROUGH TECHNOLOGY THAT ALLOWS THE MOLECULAR CHARACTERIZATION OF INFLUENZA VIRUSES AND THE GENERATION OF INFLUENZA VIRUS

VACCINES. ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tumpey, T. M. et al. Characterization of the reconstructed 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic virus. _Science_ 310, 77–80 (2005)THIS IS A PIVOTAL

PAPER THAT DESCRIBES THE RE-CREATION OF THE 1918 PANDEMIC INFLUENZA VIRUS. ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kash, J. C. et al. Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death

responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. _Nature_ 443, 578–581 (2006) ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * de Jong, M. D. et al. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is

associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. _Nature Med._ 12, 1203–1207 (2006)THIS IMPORTANT PAPER DESCRIBES HIGH LEVELS OF CYTOKINES IN HUMANS INFECTED WITH HIGHLY PATHOGENIC

AVIAN H5N1 VIRUSES. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kobasa, D. et al. Enhanced virulence of influenza A viruses with the haemagglutinin of the 1918 pandemic virus. _Nature_ 431, 703–707

(2004) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tumpey, T. M. et al. Existing antivirals are effective against influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.

USA_ 99, 13849–13854 (2002) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tumpey, T. M. et al. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus. _Proc.

Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 101, 3166–3171 (2004) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Watanabe, T. et al. Viral RNA polymerase complex promotes optimal growth of 1918 virus in the lower respiratory

tract of ferrets. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 106, 588–592 (2009) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Van Hoeven, N. et al. Human HA and polymerase subunit PB2 proteins confer transmission

of an avian influenza virus through the air. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 106, 3366–3371 (2009) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Geiss, G. K. et al. Cellular transcriptional profiling in

influenza A virus-infected lung epithelial cells: the role of the nonstructural NS1 protein in the evasion of the host innate defense and its potential contribution to pandemic influenza.

_Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 99, 10736–10741 (2002) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McAuley, J. L. et al. Expression of the 1918 influenza A virus PB1–F2 enhances the pathogenesis of

viral and secondary bacterial pneumonia. _Cell Host Microbe_ 2, 240–249 (2007) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nakajima, K., Desselberger, U. & Palese, P. Recent human

influenza A (H1N1) viruses are closely related genetically to strains isolated in 1950. _Nature_ 274, 334–339 (1978).THIS PAPER ESTABLISHED THAT THE RUSSIAN INFLUENZA IN 1977 WAS GENETICALLY

CLOSELY RELATED TO VIRUSES CIRCULATING IN HUMANS IN THE 1950S. ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Subbarao, K. et al. Characterization of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from a

child with a fatal respiratory illness. _Science_ 279, 393–396 (1998) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Claas, E. C. et al. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic

avian influenza virus. _Lancet_ 351, 472–477 (1998) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Smith, G. J. et al. Emergence and predominance of an H5N1 influenza variant in China. _Proc. Natl Acad.

Sci. USA_ 103, 16936–16941 (2006) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, H. et al. Establishment of multiple sublineages of H5N1 influenza virus in Asia: Implications for pandemic

control. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 103, 2845–2850 (2006) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Guan, Y. et al. Emergence of multiple genotypes of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in Hong Kong

SAR. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 99, 8950–8955 (2002) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Li, K. S. et al. Genesis of a highly pathogenic and potentially pandemic H5N1 influenza virus in

eastern Asia. _Nature_ 430, 209–213 (2004)THIS PAPER DESCRIBES THE FREQUENT REASSORTMENT EVENTS OF HIGHLY PATHOGENIC AVIAN H5N1 VIRUSES THAT LED TO THE EMERGENCE OF THE DOMINANT ‘GENOTYPE

Z’. ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ducatez, M. F. et al. Avian flu: multiple introductions of H5N1 in Nigeria. _Nature_ 442, 37 (2006) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tran, T. H. et

al. Avian influenza A (H5N1) in 10 patients in Vietnam. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 350, 1179–1188 (2004) PubMed Google Scholar * The Writing Committee of the World Health Organization (WHO)

Consultation on Human Influenza A/H5 Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 353, 1374–1385 (2005) Google Scholar * Chotpitayasunondh, T. et al. Human disease from

influenza A (H5N1), Thailand, 2004. _Emerg. Infect. Dis._ 11, 201–209 (2005) PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Peiris, J. S. et al. Re-emergence of fatal human influenza A subtype

H5N1 disease. _Lancet_ 363, 617–619 (2004).THIS PAPER DESCRIBES THE RE-EMERGENCE OF HUMAN INFECTIONS WITH HIGHLY PATHOGENIC AVIAN H5N1 VIRUSES IN 2003, AND ALSO EMPHASISES THE HIGH

CONCENTRATIONS OF CYTOKINES FOUND IN INFECTED INDIVIDUALS. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * To, K. F. et al. Pathology of fatal human infection associated with avian influenza

A H5N1 virus. _J. Med. Virol._ 63, 242–246 (2001) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chan, M. C. et al. Proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by influenza A (H5N1) viruses in primary human

alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells. _Respir. Res._ 6, 135 (2005) ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cheung, C. Y. et al. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human

macrophages by influenza A (H5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease? _Lancet_ 360, 1831–1837 (2002) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fraser, C. et al. Pandemic

potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): early findings. _Science_ 10.1126/science.1176062 (in the press) * Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Investigation Team Emergence of a novel

swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. _N. Engl. J Med._ 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810 (in the press)THIS HIGHLY IMPORTANT PAPER PRESENTS THE FIRST SUMMARY OF EPIDEMIOLOGICAL AND

VIROLOGICAL DATA ON THE NEW SWINE-ORIGIN H1N1 VIRUSES. * Rogers, G. N. & Paulson, J. C. Receptor determinants of human and animal influenza virus isolates: differences in receptor

specificity of the H3 hemagglutinin based on species of origin. _Virology_ 127, 361–373 (1983)THIS PAPER ESTABLISHES DIFFERENCES BETWEEN HUMAN AND AVIAN INFLUENZA VIRUSES IN RECEPTOR-BINDING

SPECIFICITY. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ito, T. et al. Molecular basis for the generation in pigs of influenza A viruses with pandemic potential. _J. Virol._ 72, 7367–7373 (1998) CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Matrosovich, M., Zhou, N., Kawaoka, Y. & Webster, R. The surface glycoproteins of H5 influenza viruses isolated from humans, chickens, and wild

aquatic birds have distinguishable properties. _J. Virol._ 73, 1146–1155 (1999) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shinya, K. et al. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the

human airway. _Nature_ 440, 435–436 (2006) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * van Riel, D. et al. H5N1 virus attachment to lower respiratory tract. _Science_ 312, 399 (2006) CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Nicholls, J. M. et al. Tropism of avian influenza A (H5N1) in the upper and lower respiratory tract. _Nature Med._ 13, 147–149 (2007) CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Stevens, J. et al. Structure of the uncleaved human H1 hemagglutinin from the extinct 1918 influenza virus. _Science_ 303, 1866–1870 (2004) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tumpey, T. M.

et al. A two-amino acid change in the hemagglutinin of the 1918 influenza virus abolishes transmission. _Science_ 315, 655–659 (2007) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gambaryan, A. et al.

Evolution of the receptor binding phenotype of influenza A (H5) viruses. _Virology_ 344, 432–438 (2006) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yamada, S. et al. Haemagglutinin mutations responsible

for the binding of H5N1 influenza A viruses to human-type receptors. _Nature_ 444, 378–382 (2006) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Auewarakul, P. et al. An avian influenza H5N1 virus

that binds to a human-type receptor. _J. Virol._ 81, 9950–9955 (2007) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Stevens, J. et al. Structure and receptor specificity of the

hemagglutinin from an H5N1 influenza virus. _Science_ 312, 404–410 (2006) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kawaoka, Y. & Webster, R. G. Sequence requirements for cleavage activation

of influenza virus hemagglutinin expressed in mammalian cells. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 85, 324–328 (1988) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Subbarao, E. K., London, W. & Murphy, B.

R. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. _J. Virol._ 67, 1761–1764 (1993) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hatta, M., Gao,

P., Halfmann, P. & Kawaoka, Y. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. _Science_ 293, 1840–1842 (2001) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mehle, A.

& Doudna, J. A. An inhibitory activity in human cells restricts the function of an avian-like influenza virus polymerase. _Cell Host Microbe_ 4, 111–122 (2008) CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Rameix-Welti, M. A., Tomoiu, A., Dos Santos Afonso, E., van der Werf, S. & Naffakh, N. Avian influenza A virus polymerase association with nucleoprotein, but

not polymerase assembly, is impaired in human cells during the course of infection. _J. Virol._ 83, 1320–1331 (2009) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hatta, M. et al. Growth of H5N1 influenza

A viruses in the upper respiratory tracts of mice. _PLoS Pathog._ 3, e133 (2007) PubMed Central Google Scholar * Massin, P., van der Werf, S. & Naffakh, N. Residue 627 of PB2 is a

determinant of cold sensitivity in RNA replication of avian influenza viruses. _J. Virol._ 75, 5398–5404 (2001) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Steel, J., Lowen, A. C.,

Mubareka, S. & Palese, P. Transmission of influenza virus in a mammalian host is increased by PB2 amino acids 627K or 627E/701N. _PLoS Pathog._ 5, e1000252 (2009) PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Li, Z. et al. Molecular basis of replication of duck H5N1 influenza viruses in a mammalian mouse model. _J. Virol._ 79, 12058–12064 (2005) CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Gabriel, G. et al. Differential polymerase activity in avian and mammalian cells determines host range of influenza virus. _J. Virol._ 81, 9601–9604 (2007) CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gabriel, G., Herwig, A. & Klenk, H. D. Interaction of polymerase subunit PB2 and NP with importin α1 is a determinant of host range of influenza A

virus. _PLoS Pathog._ 4, e11 (2008) PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Salomon, R. et al. The polymerase complex genes contribute to the high virulence of the human H5N1 influenza

virus isolate A/Vietnam/1203/04. _J. Exp. Med._ 203, 689–697 (2006) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tarendeau, F. et al. Host determinant residue lysine 627 lies on the

surface of a discrete, folded domain of influenza virus polymerase PB2 subunit. _PLoS Pathog._ 4, e1000136 (2008) PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kuzuhara, T. et al. Structural

basis of the influenza A virus RNA polymerase PB2 RNA-binding domain containing the pathogenicity-determinant lysine 627 residue. _J. Biol. Chem._ 284, 6855–6860 (2009) CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Garcia-Sastre, A. Inhibition of interferon-mediated antiviral responses by influenza A viruses and other negative-strand RNA viruses. _Virology_ 279, 375–384

(2001) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Garcia-Sastre, A. et al. Influenza A virus lacking the NS1 gene replicates in interferon-deficient systems. _Virology_ 252, 324–330 (1998)THIS PAPER

ESTABLISHES THE NS1 PROTEIN AS AN INTERFERON ANTAGONIST. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pichlmair, A. et al. RIG-I-mediated antiviral responses to single-stranded RNA bearing 5′-phosphates.

_Science_ 314, 997–1001 (2006) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Diebold, S. S., Kaisho, T., Hemmi, H., Akira, S. & Reis e Sousa, C. Innate antiviral responses by means of

TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. _Science_ 303, 1529–1531 (2004) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lund, J. M. et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by

Toll-like receptor 7. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 101, 5598–5603 (2004) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Imai, Y. et al. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4

signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. _Cell_ 133, 235–249 (2008) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Seo, S., Hoffmann, E. & Webster, R. G. Lethal H5N1 influenza

viruses escape host anti-viral cytokine responses. _Nature Med._ 8, 950–954 (2002) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Guan, Y. et al. H5N1 influenza: a protean pandemic threat. _Proc. Natl Acad.

Sci. USA_ 101, 8156–8161 (2004) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jiao, P. et al. A single-amino-acid substitution in the NS1 protein changes the pathogenicity of H5N1 avian influenza

viruses in mice. _J. Virol._ 82, 1146–1154 (2008) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Li, Z. et al. The NS1 gene contributes to the virulence of H5N1 avian influenza viruses. _J. Virol._ 80,

11115–11123 (2006) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Obenauer, J. C. et al. Large-scale sequence analysis of avian influenza isolates. _Science_ 311, 1576–1580 (2006) ADS CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Jackson, D., Hossain, M. J., Hickman, D., Perez, D. R. & Lamb, R. A. A new influenza virus virulence determinant: the NS1 protein four C-terminal residues

modulate pathogenicity. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 105, 4381–4386 (2008) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, W. et al. A novel influenza A virus mitochondrial protein that induces

cell death. _Nature Med._ 7, 1306–1312 (2001) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zamarin, D., Garcia-Sastre, A., Xiao, X., Wang, R. & Palese, P. Influenza virus PB1–F2 protein induces cell

death through mitochondrial ANT3 and VDAC1. _PLoS Pathog._ 1, e4 (2005) PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mazur, I. et al. The proapoptotic influenza A virus protein PB1–F2 regulates

viral polymerase activity by interaction with the PB1 protein. _Cell. Microbiol._ 10, 1140–1152 (2008) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Conenello, G. M., Zamarin, D., Perrone, L. A., Tumpey,

T. & Palese, P. A single mutation in the PB1–F2 of H5N1 (HK/97) and 1918 influenza A viruses contributes to increased virulence. _PLoS Pathog._ 3, e141 (2007) PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Kiso, M. et al. Resistant influenza A viruses in children treated with oseltamivir: descriptive study. _Lancet_ 364, 759–765 (2004) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Poland, G. A.,

Jacobson, R. M. & Ovsyannikova, I. G. Influenza virus resistance to antiviral agents: a plea for rational use. _Clin. Infect. Dis._ 48, 1254–1256 (2009) PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Le, Q. M. et al. Avian flu: isolation of drug-resistant H5N1 virus. _Nature_ 437, 1108 (2005) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * de Jong, M. D. et al. Oseltamivir resistance

during treatment of influenza A (H5N1) infection. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 353, 2667–2672 (2005) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Weinstock, D. M., Gubareva, L. V. & Zuccotti, G. Prolonged

shedding of multidrug-resistant influenza A virus in an immunocompromised patient. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 348, 867–868 (2003) PubMed Google Scholar * Baz, M., Abed, Y., McDonald, J. &

Boivin, G. Characterization of multidrug-resistant influenza A/H3N2 viruses shed during 1 year by an immunocompromised child. _Clin. Infect. Dis._ 43, 1555–1561 (2006) CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Ison, M. G., Gubareva, L. V., Atmar, R. L., Treanor, J. & Hayden, F. G. Recovery of drug-resistant influenza virus from immunocompromised patients: a case series. _J. Infect.

Dis._ 193, 760–764 (2006) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Collins, P. J. et al. Crystal structures of oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus neuraminidase mutants. _Nature_ 453, 1258–1261

(2008) ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gubareva, L. V., Matrosovich, M. N., Brenner, M. K., Bethell, R. C. & Webster, R. G. Evidence for zanamivir resistance in an immunocompromised

child infected with influenza B virus. _J. Infect. Dis._ 178, 1257–1262 (1998) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Babu, Y. S. et al. BCX-1812 (RWJ-270201): discovery of a novel, highly potent,

orally active, and selective influenza neuraminidase inhibitor through structure-based drug design. _J. Med. Chem._ 43, 3482–3486 (2000) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yamashita, M. et al.

CS-8958, a prodrug of the new neuraminidase inhibitor R-125489, shows long-acting anti-influenza virus activity. _Antimicrob. Agents Chemother._ 53, 186–192 (2009) CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Furuta, Y. et al. _In vitro_ and _in vivo_ activities of anti-influenza virus compound T-705. _Antimicrob. Agents Chemother._ 46, 977–981 (2002) CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Sui, J. et al. Structural and functional bases for broad-spectrum neutralization of avian and human influenza A viruses. _Nature Struct. Mol. Biol._ 16, 265–273 (2009)

MathSciNet CAS Google Scholar * Belshe, R. B. et al. Live attenuated versus inactivated influenza vaccine in infants and young children. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 356, 685–696 (2007) CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Treanor, J. J., Campbell, J. D., Zangwill, K. M., Rowe, T. & Wolff, M. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated subvirion influenza A (H5N1) vaccine. _N. Engl. J.

Med._ 354, 1343–1351 (2006) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bresson, J. L. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated split-virion influenza A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (H5N1) vaccine: phase

I randomised trial. _Lancet_ 367, 1657–1664 (2006) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lin, J. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated adjuvanted whole-virion influenza A (H5N1)

vaccine: a phase I randomised controlled trial. _Lancet_ 368, 991–997 (2006) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bernstein, D. I. et al. Effects of adjuvants on the safety and immunogenicity of

an avian influenza H5N1 vaccine in adults. _J. Infect. Dis._ 197, 667–675 (2008) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Stephenson, I. et al. Antigenically distinct MF59-adjuvanted vaccine to boost

immunity to H5N1. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 359, 1631–1633 (2008) CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Levie, K. et al. An adjuvanted, low-dose, pandemic influenza A (H5N1) vaccine candidate is safe,

immunogenic, and induces cross-reactive immune responses in healthy adults. _J. Infect. Dis._ 198, 642–649 (2008) PubMed Google Scholar * Suguitan, A. L. et al. Live, attenuated influenza

A H5N1 candidate vaccines provide broad cross-protection in mice and ferrets. _PLoS Med._ 3, e360 (2006) PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fan, S. et al. Immunogenicity and

protective efficacy of a live attenuated H5N1 vaccine in nonhuman primates. _PLoS Pathog._ 5, e1000409 (2009) PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schotsaert, M., De, F. M., Fiers, W.

& Saelens, X. Universal M2 ectodomain-based influenza A vaccines: preclinical and clinical developments. _Expert Rev. Vaccines_ 8, 499–508 (2009) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Mahmood, K. et al. H5N1 VLP vaccine induced protection in ferrets against lethal challenge with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses. _Vaccine_ 26, 5393–5399 (2008) CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Gao, W. et al. Protection of mice and poultry from lethal H5N1 avian influenza virus through adenovirus-based immunization. _J. Virol._ 80, 1959–1964 (2006) CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hoelscher, M. A. et al. Development of adenoviral-vector-based pandemic influenza vaccine against antigenically distinct human H5N1 strains in mice.

_Lancet_ 367, 475–481 (2006) CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We apologize to our colleagues whose critical contributions to influenza virus

research could not be cited owing to the number of references permitted. We thank K. Wells for editing the manuscript. We also thank M. Ozawa and others in our laboratories who contributed

to the data cited in this review. Our original research was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Public Health Service research grants; by the Center for

Research on Influenza Pathogenesis (CRIP) funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Contract HHSN266200700010C), Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research, by a

contract research fund for the Program of Founding Research Centers for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology,

by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Health and by ERATO (Japan Science and Technology Agency). G.N. is named as co-inventor on several patents about influenza virus reverse genetics

and/or the development of influenza virus vaccines or antivirals. Y.K. is named as inventor/co-inventor on several patents about influenza virus reverse genetics and/or the development of

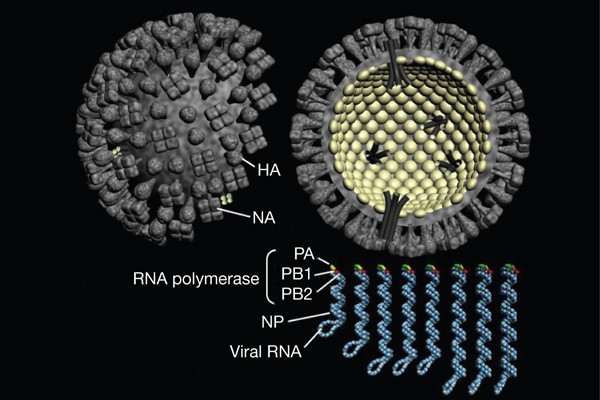

influenza virus vaccines or antivirals. Figures 1 and 2 were modified from Orthomyxoviruses: influenza, in Topley and Wilson's Microbiology and Microbial Infections: Virology (Hodder

Arnold, 2005); Fig. 3 was modified from Orthomyxoviruses, in Fields Virology (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007). AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS G.N. wrote the manuscript. T.N. provided the

electron microscopic picture. Y.K. also wrote the manuscript. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Pathobiological Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison,

Wisconsin 53711, USA, Gabriele Neumann & Yoshihiro Kawaoka * International Research Center for Infectious Diseases,, Takeshi Noda & Yoshihiro Kawaoka * Division of Virology,

Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 108-8639, Japan Yoshihiro Kawaoka * ERATO Infection-Induced Host Responses Project, Japan

Science and Technology Agency, Saitama 332-0012, Japan Yoshihiro Kawaoka Authors * Gabriele Neumann View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Takeshi Noda View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yoshihiro Kawaoka View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Yoshihiro Kawaoka. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS [Competing Interests: Y.K. has received speaker’s honoraria from Chugai

Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Sankyo, Toyama Chemical, Wyeth and GlaxoSmithKline; grant support from Chugai Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo Pharmaceutical and Toyama Chemical; consulting fee

from Theraclone Sciences and Fort Dodge Animal Health; and is a founder of FluGen. G.N. has received consulting fee from Theraclone Sciences and is a founder of FluGen.] ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the full-text HTML version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature. POWERPOINT SLIDES POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG.

1 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 2 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 3 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 4 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 5 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE

THIS ARTICLE Neumann, G., Noda, T. & Kawaoka, Y. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. _Nature_ 459, 931–939 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08157

Download citation * Received: 12 May 2009 * Accepted: 26 May 2009 * Published: 14 June 2009 * Issue Date: 18 June 2009 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08157 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone

you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the

Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative