Temporally distinct myeloid cell responses mediate damage and repair after cerebrovascular injury

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Cerebrovascular injuries can cause severe edema and inflammation that adversely affect human health. Here, we observed that recanalization after successful endovascular thrombectomy

for acute large vessel occlusion was associated with cerebral edema and poor clinical outcomes in patients who experienced hemorrhagic transformation. To understand this process, we

developed a cerebrovascular injury model using transcranial ultrasound that enabled spatiotemporal evaluation of resident and peripheral myeloid cells. We discovered that injurious and

reparative responses diverged based on time and cellular origin. Resident microglia initially stabilized damaged vessels in a purinergic receptor–dependent manner, which was followed by an

influx of myelomonocytic cells that caused severe edema. Prolonged blockade of myeloid cell recruitment with anti-adhesion molecule therapy prevented severe edema but also promoted neuronal

destruction and fibrosis by interfering with vascular repair subsequently orchestrated by proinflammatory monocytes and proangiogenic repair-associated microglia (RAM). These data

demonstrate how temporally distinct myeloid cell responses can contain, exacerbate and ultimately repair a cerebrovascular injury. Access through your institution Buy or subscribe This is a

preview of subscription content, access via your institution ACCESS OPTIONS Access through your institution Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals Get Nature+, our best-value

online-access subscription $32.99 / 30 days cancel any time Learn more Subscribe to this journal Receive 12 print issues and online access $209.00 per year only $17.42 per issue Learn more

Buy this article * Purchase on SpringerLink * Instant access to full article PDF Buy now Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout ADDITIONAL ACCESS OPTIONS:

* Log in * Learn about institutional subscriptions * Read our FAQs * Contact customer support SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS LONG-TERM MICROGLIAL PHASE-SPECIFIC DYNAMICS DURING

SINGLE VESSEL OCCLUSION AND RECANALIZATION Article Open access 19 August 2022 REPAIR-ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGES INCREASE AFTER EARLY-PHASE MICROGLIA ATTENUATION TO PROMOTE ISCHEMIC STROKE

RECOVERY Article Open access 31 March 2025 STROKE INDUCES DISEASE-SPECIFIC MYELOID CELLS IN THE BRAIN PARENCHYMA AND PIA Article Open access 17 February 2022 DATA AVAILABILITY The data that

support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. There are no restrictions on data availability. Bulk RNA-seq data are available in the NCBI Gene

Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE161424. Source data are provided with this paper. REFERENCES * Mastorakos, P. & McGavern, D. The anatomy and immunology of vasculature in the

central nervous system. _Sci. Immunol_. 4, eaav0492 (2019). * Donkor, E. S. Stroke in the 21st century: a snapshot of the burden, epidemiology, and quality of life. _Stroke Res. Treat._

2018, 3238165 (2018). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Maxwell, W. L., Irvine, A., Adams, J. H., Graham, D. I. & Gennarelli, T. A. Response of cerebral microvasculature to brain

injury. _J. Pathol._ 155, 327–335 (1988). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Marcolini, E., Stretz, C. & DeWitt, K. M. Intracranial hemorrhage and intracranial hypertension.

_Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am._ 37, 529–544 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Simard, J. M., Kent, T. A., Chen, M., Tarasov, K. V. & Gerzanich, V. Brain oedema in focal ischaemia:

molecular pathophysiology and theoretical implications. _Lancet Neurol._ 6, 258–268 (2007). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Mestre, H. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid

influx drives acute ischemic tissue swelling. _Science_ 367, eaax7171 (2020). * Kriz, J. Inflammation in ischemic brain injury: timing is important. _Crit. Rev. Neurobiol._ 18, 145–157

(2006). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Yang, Y. & Rosenberg, G. A. Matrix metalloproteinases as therapeutic targets for stroke. _Brain Res._ 1623, 30–38 (2015). Article PubMed

PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Nadareishvili, Z. et al. An MRI hyperintense acute reperfusion marker is related to elevated peripheral monocyte count in acute ischemic stroke. _J.

Neuroimaging_ 28, 57–60 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hermann, D. M., Kleinschnitz, C. & Gunzer, M. Implications of polymorphonuclear neutrophils for ischemic stroke and

intracerebral hemorrhage: predictive value, pathophysiological consequences and utility as therapeutic target. _J. Neuroimmunol._ 321, 138–143 (2018). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Manglani, M. & McGavern, D. B. Intravital imaging of neuroimmune interactions through a thinned skull. _Curr. Protoc. Immunol._ 120, 24.2.1–24.2.12 (2018). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Roth, T. L. et al. Transcranial amelioration of inflammation and cell death after brain injury. _Nature_ 505, 223–228 (2014). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Promeneur,

D., Lunde, L. K., Amiry-Moghaddam, M. & Agre, P. Protective role of brain water channel AQP4 in murine cerebral malaria. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 110, 1035–1040 (2013). Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Serbina, N. V. & Pamer, E. G. Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. _Nat.

Immunol._ 7, 311–317 (2006). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Rua, R. et al. Infection drives meningeal engraftment by inflammatory monocytes that impairs CNS immunity. _Nat.

Immunol._ 20, 407–419 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Zhang, Y. B. et al. Early neurological deterioration after recanalization treatment in patients with

acute ischemic stroke: a retrospective study. _Chin. Med J. (Engl.)_ 131, 137–143 (2018). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Peng, G. et al. Risk factors for decompressive craniectomy

after endovascular treatment in acute ischemic stroke. _Neurosurg. Rev._ 43, 1357–1364 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, X. et al. A prediction model of brain edema after

endovascular treatment in patients with acute ischemic stroke. _J. Neurol. Sci._ 407, 116507 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Nimmerjahn, A., Kirchhoff, F. & Helmchen, F.

Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. _Science_ 308, 1314–1318 (2005). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Davalos, D. et al. ATP mediates

rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. _Nat. Neurosci._ 8, 752–758 (2005). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Lou, N. et al. Purinergic receptor P2RY12-dependent

microglial closure of the injured blood–brain barrier. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 113, 1074–1079 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Ahn, S. J., Anrather, J.,

Nishimura, N. & Schaffer, C. B. Diverse inflammatory response after cerebral microbleeds includes coordinated microglial migration and proliferation. _Stroke_ 49, 1719–1726 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fernandez-Lopez, D. et al. Microglial cells prevent hemorrhage in neonatal focal arterial stroke. _J. Neurosci._ 36, 2881–2893 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Fumagalli, S., Perego, C., Ortolano, F. & De Simoni, M. G. CX3CR1 deficiency induces an early protective inflammatory environment

in ischemic mice. _Glia_ 61, 827–842 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Tang, Z. et al. CX3CR1 deficiency suppresses activation and neurotoxicity of microglia/macrophage in

experimental ischemic stroke. _J. Neuroinflammation_ 11, 26 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Jolivel, V. et al. Perivascular microglia promote blood vessel

disintegration in the ischemic penumbra. _Acta Neuropathol._ 129, 279–295 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kim, J. V., Kang, S. S., Dustin, M. L. & McGavern, D. B.

Myelomonocytic cell recruitment causes fatal CNS vascular injury during acute viral meningitis. _Nature_ 457, 191–195 (2009). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Relton, J. K. et al.

Inhibition of α4 integrin protects against transient focal cerebral ischemia in normotensive and hypertensive rats. _Stroke_ 32, 199–205 (2001). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Zhang, L. et al. Effects of a selective CD11b/CD18 antagonist and recombinant human tissue plasminogen activator treatment alone and in combination in a rat embolic model of stroke. _Stroke_

34, 1790–1795 (2003). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Langhauser, F. et al. Blocking of α4 integrin does not protect from acute ischemic stroke in mice. _Stroke_ 45, 1799–1806

(2014). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Llovera, G. et al. Results of a preclinical randomized controlled multicenter trial (pRCT): anti-CD49d treatment for acute brain ischemia.

_Sci. Transl. Med._ 7, 299ra121 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Krams, M. et al. Acute Stroke Therapy by Inhibition of Neutrophils (ASTIN): an adaptive dose–response study of

UK-279,276 in acute ischemic stroke. _Stroke_ 34, 2543–2548 (2003). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Elkins, J. et al. Safety and efficacy of natalizumab in patients with acute

ischaemic stroke (ACTION): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2 trial. _Lancet Neurol._ 16, 217–226 (2017). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Xiong, Y., Mahmood, A.

& Chopp, M. Angiogenesis, neurogenesis and brain recovery of function following injury. _Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs_ 11, 298–308 (2010). PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar *

Krupinski, J., Kaluza, J., Kumar, P., Kumar, S. & Wang, J. M. Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. _Stroke_ 25, 1794–1798 (1994). Article PubMed CAS Google

Scholar * Dimitrijevic, O. B., Stamatovic, S. M., Keep, R. F. & Andjelkovic, A. V. Absence of the chemokine receptor CCR2 protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice.

_Stroke_ 38, 1345–1353 (2007). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Hammond, M. D. et al. CCR2+Ly6Chi inflammatory monocyte recruitment exacerbates acute disability following

intracerebral hemorrhage. _J. Neurosci._ 34, 3901–3909 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gliem, M. et al. Macrophages prevent hemorrhagic infarct transformation in

murine stroke models. _Ann. Neurol._ 71, 743–752 (2012). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Gliem, M. et al. Macrophage-derived osteopontin induces reactive astrocyte polarization and

promotes re-establishment of the blood brain barrier after ischemic stroke. _Glia_ 63, 2198–2207 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Wattananit, S. et al. Monocyte-derived macrophages

contribute to spontaneous long-term functional recovery after stroke in mice. _J. Neurosci._ 36, 4182–4195 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Fang, W. et al.

CCR2-dependent monocytes/macrophages exacerbate acute brain injury but promote functional recovery after ischemic stroke in mice. _Theranostics_ 8, 3530–3543 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed

Central CAS Google Scholar * Keren-Shaul, H. et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer’s disease. _Cell_ 169, 1276–1290 (2017). Article PubMed

CAS Google Scholar * Apte, R. S., Chen, D. S. & Ferrara, N. VEGF in signaling and disease: beyond discovery and development. _Cell_ 176, 1248–1264 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed

Central CAS Google Scholar * Margaritescu, O., Pirici, D. & Margaritescu, C. VEGF expression in human brain tissue after acute ischemic stroke. _Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol._ 52,

1283–1292 (2011). PubMed Google Scholar * Xie, L., Mao, X., Jin, K. & Greenberg, D. A. Vascular endothelial growth factor-B expression in postischemic rat brain. _Vasc. Cell_ 5, 8

(2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Sankowski, R. et al. Mapping microglia states in the human brain through the integration of high-dimensional techniques. _Nat.

Neurosci._ 22, 2098–2110 (2019). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Brandenburg, S. et al. Resident microglia rather than peripheral macrophages promote vascularization in brain tumors

and are source of alternative pro-angiogenic factors. _Acta Neuropathol._ 131, 365–378 (2016). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Vannella, K. M. & Wynn, T. A. Mechanisms of organ

injury and repair by macrophages. _Annu. Rev. Physiol._ 79, 593–617 (2017). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Wynn, T. A. & Ramalingam, T. R. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic

translation for fibrotic disease. _Nat. Med._ 18, 1028–1040 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Duffield, J. S. et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals

distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. _J. Clin. Invest._ 115, 56–65 (2005). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Higashida, R. T. et al. Trial design

and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. _Stroke_ 34, e109–e137 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Luby, M., Bykowski, J. L.,

Schellinger, P. D., Merino, J. G. & Warach, S. Intra- and interrater reliability of ischemic lesion volume measurements on diffusion-weighted, mean transit time and fluid-attenuated

inversion recovery MRI. _Stroke_ 37, 2951–2956 (2006). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hacke, W. et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic

therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. _Lancet_ 352, 1245–1251 (1998). Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Paigen, B., Morrow, A., Brandon, C., Mitchell, D. & Holmes, P. Variation in susceptibility to atherosclerosis among inbred strains of mice. _Atherosclerosis_ 57, 65–73

(1985). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Jung, S. et al. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion.

_Mol. Cell Biol._ 20, 4106–4114 (2000). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Saederup, N. et al. Selective chemokine receptor usage by central nervous system myeloid cells

in CCR2-red fluorescent protein knock-in mice. _PLoS ONE_ 5, e13693 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ganat, Y. M. et al. Early postnatal astroglial cells produce

multilineage precursors and neural stem cells in vivo. _J. Neurosci._ 26, 8609–8621 (2006). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Madisen, L. et al. A robust and

high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. _Nat. Neurosci._ 13, 133–140 (2010). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Yona, S. et al. Fate mapping

reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. _Immunity_ 38, 79–91 (2013). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Liao, Y., Day, K. H., Damon, D. N.

& Duling, B. R. Endothelial cell-specific knockout of connexin 43 causes hypotension and bradycardia in mice. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 98, 9989–9994 (2001). Article PubMed PubMed

Central CAS Google Scholar * Calera, M. R. et al. Connexin43 is required for production of the aqueous humor in the murine eye. _J. Cell Sci._ 119, 4510–4519 (2006). Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Hughes, E. G., Kang, S. H., Fukaya, M. & Bergles, D. E. Oligodendrocyte progenitors balance growth with self-repulsion to achieve homeostasis in the adult brain.

_Nat. Neurosci._ 16, 668–676 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Faust, N., Varas, F., Kelly, L. M., Heck, S. & Graf, T. Insertion of enhanced green

fluorescent protein into the lysozyme gene creates mice with green fluorescent granulocytes and macrophages. _Blood_ 96, 719–726 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Yata, Y. et

al. DNase I-hypersensitive sites enhance α1(I) collagen gene expression in hepatic stellate cells. _Hepatology_ 37, 267–276 (2003). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Spangenberg, E. et

al. Sustained microglial depletion with CSF1R inhibitor impairs parenchymal plaque development in an Alzheimer’s disease model. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 3758 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Wyder, L. et al. Increased expression of H/T-cadherin in tumor-penetrating blood vessels. _Cancer Res_. 60, 4682–4688 (2000). PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Wiewrodt, R. et al. Size-dependent intracellular immunotargeting of therapeutic cargoes into endothelial cells. _Blood_ 99, 912–922 (2002). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * McQualter,

J. L. et al. Endogenous fibroblastic progenitor cells in the adult mouse lung are highly enriched in the Sca-1 positive cell fraction. _Stem Cells_ 27, 623–633 (2009). Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Ohsawa, K., Imai, Y., Kanazawa, H., Sasaki, Y. & Kohsaka, S. Involvement of Iba1 in membrane ruffling and phagocytosis of macrophages/microglia. _J. Cell Sci._ 113,

3073–3084 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Sasaki, Y., Ohsawa, K., Kanazawa, H., Kohsaka, S. & Imai, Y. Iba1 is an actin-cross-linking protein in macrophages/microglia.

_Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun._ 286, 292–297 (2001). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Kanazawa, H., Ohsawa, K., Sasaki, Y., Kohsaka, S. & Imai, Y. Macrophage/microglia-specific

protein Iba1 enhances membrane ruffling and Rac activation via phospholipase C-γ-dependent pathway. _J. Biol. Chem._ 277, 20026–20032 (2002). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Linker,

K. E. et al. Microglial activation increases cocaine self-administration following adolescent nicotine exposure. _Nat. Commun._ 11, 306 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google

Scholar * Skorkowska, A. et al. Effect of combined prenatal and adult benzophenone-3 dermal exposure on factors regulating neurodegenerative processes, blood hormone levels, and

hematological parameters in female rats. _Neurotox. Res._ 37, 683–701 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Lentz, M. R. et al. Diffusion tensor and volumetric

magnetic resonance measures as biomarkers of brain damage in a small animal model of HIV. _PLoS ONE_ 9, e105752 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Krause, T. A.,

Alex, A. F., Engel, D. R., Kurts, C. & Eter, N. VEGF-production by CCR2-dependent macrophages contributes to laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. _PLoS ONE_ 9, e94313 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Russo, M. V. & McGavern, D. B. Inflammatory neuroprotection following traumatic brain injury. _Science_ 353, 783–785 (2016). Article

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was supported by the intramural program at the NINDS, NIH. We thank A. Hoofring in the NIH

Medical Arts Design Section for generating the illustration shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. We thank A. Elkahloun and W. Wu in the National Human Genome Research Institute Microarray core for

their assistance with the RNA-seq experiment. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Viral Immunology & Intravital Imaging Section, National Institute of Neurological Disorders

and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA Panagiotis Mastorakos, Nicole Mihelson & Dorian B. McGavern * Department of Surgical Neurology, National Institute of

Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA Panagiotis Mastorakos * Acute Cerebrovascular Diagnostics Unit, National Institute of Neurological

Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA Marie Luby, Amie W. Hsia & Lawrence Latour * Frank Laboratory, Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Clinical Center,

National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA Scott R. Burks, Jaclyn Witko & Joseph A. Frank * National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health,

Bethesda, MD, USA Kory Johnson * MedStar Washington Hospital Center Comprehensive Stroke Center, Washington, DC, USA Amie W. Hsia * National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and

Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA Joseph A. Frank Authors * Panagiotis Mastorakos View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Nicole Mihelson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Marie Luby View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Scott R. Burks View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kory Johnson View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Amie W. Hsia View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jaclyn Witko View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Joseph A. Frank View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lawrence Latour View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Dorian B. McGavern View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS P.M. and N.M. performed the data acquisition and analysis. P.M., M.L., A.W.H. and L.L. contributed to the design, acquisition and analysis of clinical data. S.R.B., J.W. and

J.A.F. contributed to optimization of the ultrasound model and performed the mouse MRI studies. K.J. conducted computation analyses of RNA-seq data. P.M. and D.B.M. wrote and edited the

manuscript. D.B.M. supervised and directed the project and participated in data acquisition and analysis. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Dorian B. McGavern. ETHICS DECLARATIONS

COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Neuroscience_ thanks Thiruma Arumugam, Jonathan Godbout, and the other,

anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. EXTENDED DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 1 MODEL OF ULTRASOUND-INDUCED INJURY. Following surgical generation of a 2 mm x 2 mm x 15 µm thinned skull window, microbubbles

were injected intravenously and a drop of aCSF was placed atop the thinned skull bone. Through this aCSF we applied low intensity pulse ultrasound (LIPUS) using a Mettler Sonicator 740x with

a 5 cm2 planar dual frequency applicator operating at 1 MHz, ~200KPa peak negative pressure with duty cycle 10% and 1 ms burst. LIPUS induced acoustic cavitation of the microbubbles.

Microbubble oscillation, inertial cavitation, and explosion caused internal injury of blood vessel walls, exposing the brain parenchyma to blood contents. This injury creates a relative

column of injury in the brain tissue beneath the thinned skull window, as the ultrasound waves are not strong enough to pass through the surrounding intact bone. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 2

CHARACTERIZATION OF THE CEREBROVASCULAR INJURY MODEL. A, Magnified images of the 2 mm x 2 mm x 15 µm thinned skull window pre- and post-injury depict petechial intraparenchymal hemorrhages

at 10 min post-injury. B, Macroscopic depiction of a mouse brain 24 h following posterior sonication injury. C, Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrates a median survival of 2 days after posterior

sonication injury. Anterior sonication injury does not result in fatalities. Cumulative data are shown from 2 independent experiments with 10 mice per group (P = 2.96e-10, Log-rank test). D,

A graph showing quantification of cerebral water content demonstrates increased edema 24 h after sonication with 7.7% and 7.1% increase in water content after anterior and posterior injury,

respectively, relative to uninjured control mice (**P < 0.01, anterior P = 2.9e-7, posterior p = 1.3e-6, One-way ANOVA/Tukey test). Cumulative data are shown from 2 independent

experiments with 5 mice per group per experiment. E, A graph showing quantification of fluorescein extravasation into the ipsilateral versus contralateral brain hemisphere at the denoted

time points post-injury (**P < 0.01, One-way ANOVA/Tukey test). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4 mice per group per experiment, 2 samples were above the

detection limit and not included. F-H, High parameter flow cytometric analysis of brain biopsies from mice at d1 and d6 post-injury relative to uninjured controls. A UMAP plot of

concatenated live cells from each group is shown in panel F. A heatmap of Ter-119 signal on a UMAP plot reflecting the concatenated cell populations from a single experiment is shown in

panel G. Panel H shows a scatter plot depicting the absolute Ter-119+ RBCs. Cumulative data are shown from 2 independent experiments (Uninjured n = 8, d1 n = 8, d6 n = 9, **P < 0.01,

One-way ANOVA/Tukey test; gating strategy in Supplementary Fig. 1A). Graphs D, E, H show the mean ± SD. Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 3 MICROGLIA DEPLETION INCREASES BBB LEAKAGE,

INTRAPARENCHYMAL HEMORRHAGE, MYELOID CELL INVASION AND VASCULAR ENDOTHELIUM ACTIVATION. A, Intravital microscopy of CX3CR1gfp/wt (green) mice 20 min after injury shows extensive

intraparenchymal EB (red) extravasation following microglia depletion using an alternate CSF1R inhibitor, PLX5622, to that used in Fig. 2c,d. B, EB extravasation assay based on intravital

microscopy time lapses depicts increased BBB leakage 20-40 min after microglia depletion using PLX5622. Graph depicts mean ± SD of cumulative data from 2 independent experiments (n = 12 mice

per group, **P = 3.9e-9, two-tailed Student’s t-test). C, Confocal microscopy images of cortical brain sections from of naive and microglia depleted Cx3CR1gfp/wt (green) mice 1 h following

injury. Mice received an i.v. injection of fluorescent fibrinogen (white) and tomato-lectin (red). Larger and more diffuse intraparenchymal fibrinogen is observed in mice treated with

PLX3397 (CSF1R inhibitor). D, Image-based quantification of fibrin burden in the brain parenchyma. Graph depicts mean ± SD of cumulative data from 2 independent experiments (Ctrl n = 10,

CSF1R inh n = 13, **P = 0.00017, Mann–Whitney U test). E, Two-photon microscopy images captured in the cerebral cortex of injured LysMgfp/wt mice treated with vehicle or PLX3397 show LysM+

myelomonocytic cell (green) invasion at 20 min post-injury. Tomato-lectin is shown in red. F, Image based quantification of myelomonocytic infiltration. Graph depicts mean ± SD of cumulative

data from 2 independent experiments (Ctrl n = 8, CSF1R inh n = 12, **P = 0.0002, Mann–Whitney U test). G, Intravital microscopy images in the cerebral cortex of vehicle versus PLX3397

treated B6 mice at 24 h post-injury. Prior to imaging, mice received an i.v. injection of APC-anti-CD106 (VCAM-1; red) and PE-anti-CD54 (ICAM-1; green), which revealed increased endothelial

expression in PLX3397 treated mice. Representative images are from 2 independent experiments with 3 mice per group. H, qPCR analysis of ICAM and VCAM expression in vehicle vs. PLX3397

treated B6 mice at 24 h post-injury. Graph depicts mean ± SD of cumulative data from 2 independent experiments (n = 6 mice per group, Vcam1 P = 3.58e-5, Icam1 P = 0.0072, Two-way

ANOVA/Holm-Sidak test). I, Heatmap shows qPCR analysis of genes encoding for acute inflammation-related proteins in vehicle vs. PLX3397-treated B6 mice. The fold increase in gene expression

was calculated relative to the uninjured contralateral hemisphere for each mouse at 24 h post-injury. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 5 mice per group per

experiment (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, multiple t tests with Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons correction, source data in Supplementary Table S3). CSF1R inh refers to PLX3397. Source data

EXTENDED DATA FIG. 4 REPRESENTATIVE IMAGES ESTABLISHING A ROLE FOR P2RY12 RECEPTOR AND CX43 HEMICHANNELS IN MICROGLIAL ROSETTING. Data from these experiments are provided in Fig. 2g,h,i. A,

Intravital microscopy images in the cerebral cortex of Cx3CR1gfp/wt (green) mice 20 min post-injury. Mice were treated transcranially with a vehicle or a P2RY12 inhibitor (MeSAMP).

Intravenous injection of EB (red) revealed increased intraparenchymal extravasation following pre-treatment with the P2RY12 inhibitor. Images are representative of experimental data graphed

in Fig. 2g. B, Intravital microscopy images in the cerebral cortex of Cx3CR1gfp/wt (green) mice 20 min post-injury. Mice were treated transcranially with a vehicle or a Cx43 inhibitor

(carbenoxolone). Intravenous injection of EB (red) revealed extensive intraparenchymal extravasation following pre-treatment with the Cx43 inhibitor. Images are representative of

experimental data graphed in Fig. 2g. C, Confocal microscopy images of brain sections from littermate control (GFAPCreER-Cx43f/wt and GFAPCreER-Cx43wt/wt) vs. GFAPCreER-Cx43f/f mice 1 h

after injury show decreased microglia rosetting in GFAPCreER-Cx43f/f mice. Microglia rosettes were identified with Iba1 staining (green). Tomato-lectin+ blood vessels are shown in white.

Images are representative of experimental data graphed in Fig. 2h. D, Intravital microscopy images from the cerebral cortex of control (GFAPCreER-Cx43f/wt, GFAPCreER-Cx43wt/wt) vs.

GFAPCreER-Cx43f/f mice 20 min after injury. Intravenous injection of EB (red) revealed extensive intraparenchymal extravasation in GFAPCreER-Cx43f/f mice. Images are representative of

experimental data graphed in Fig. 2i. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 5 IMMUNE LANDSCAPE IN THE CEREBRAL CORTEX FOLLOWING CEREBROVASCULAR INJURY IN CX3CR1GFP/WTCCR2RFP/WT MICE. Quantification of these

flow cytometric experiments is provided in Fig. 3c,f, gating strategy in Supplementary Fig. 1B. The panel used for these experiments includes: Cx3CR1-GFP, Ly6C BB790, MHCII BV480, CD11b

BV570, CD115 BV605, CD24 BV650, CD11c BV785, P2RY12 PE, CCR2-RFP, Ter-119 PE/Cy5, CD206 PE/Cy7, CD45 BUV395, CD4 BUV496, Ly6G BUV563, CD19 BUV661, CD44 BUV737, CD8 BUV805, F4/80 APC-R700,

TCRb APC/Cy7 and live/dead fixable blue cell staining kit. Plots were pre-gated for CD45 + Ter119- live cells and subsequently analyzed using an unsupervised clustering algorithm to group

data into subpopulations (PhenoGraph) and visualized using UMAP. For each experiment, the first row depicts the concatenated samples of 4 independent mice per group, and the legend shows the

combined phenograph clusters corresponding to different immune cell populations. The second and third rows show six representative heatmaps of different markers used to identify the

different immune cell populations. A, Immune landscape at 1 d and 6 d post-injury compared to uninjured mice. B, Immune landscape 1 d after injury in mice treated with bolus αLFA1/VLA4 or

isotype control antibodies relative to uninjured mice. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 6 EFFECT OF MYELOMONOCYTIC CELL INVASION ON CEREBRAL EDEMA AND SURVIVAL AFTER INJURY. This figure depicts

quantification of cerebral water content following anterior and posterior injury as well as survival after posterior injury in four different experimental paradigms. Left column shows

quantification of cerebral water content in the ipsilateral hemisphere 1 d after anterior injury in the treatment vs control group compared to the contralateral hemisphere. The middle column

shows quantification of cerebral water content after posterior injury when mice reached the survival end point or 5 d post-injury in the treatment vs. control group relative to the

contralateral hemisphere (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Two-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak test). Graphs depict mean ± SD. The right column shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves after posterior injury in

treatment vs. control groups (Log-rank test). A, Effect of αGr-1 vs. isotype control bolus administration 24 h prior to injury. B, Effect of αLFA1/VLA4 vs. isotype control bolus

administration 24 h prior to injury. C, Water content and survival after injury in CCR2 KO mice compared to B6 mice treated with isotype or αLFA1/VLA4 24 h prior to injury. D, Effect of

αLy6G or αLFA1/VLA4 vs. isotype control administration 24 h prior to injury. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4 or 5 mice per group. Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 7

COMBINED ΑLFA1 AND ΑVLA4 TREATMENT IS REQUIRED TO PREVENT CEREBRAL EDEMA AND DEATH. A-C, Effect of bolus treatment with αLFA1/VLA4, αLFA1, αVLA4 or isotype control on cerebral water content

24 h after anterior (A) or posterior (B, C) injury. Data compilation from 2 independent experiments. The antibodies were administered 24 h before injury. Cerebral water content was

determined 1d after anterior injury (A) and 5d or when mice reached the survival endpoint after posterior injury (B). Graphs depict mean ± SD (isotype n = 8, αLV n = 8, αLFA1 n = 4 or 5,

αVLA4 n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Two-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak test). Panel C demonstrates Kaplan-Meier survival curve following posterior injury (isotype n = 9, αLV n = 10, αLFA1 n = 6,

αVLA4 n = 6, Logrank test P = 3.4e-5). D, Intravital microscopy images of the cerebral cortex from uninjured vs. injured B6 mice 1 h following i.v. administration of APC-anti-CD106 (VCAM-1;

red) and PE-anti-CD54 (ICAM-1; green) show increased endothelial ICAM and VCAM expression 24 h after injury. Two representative images from the injured mice depict inter-sample and

inter-vessel variability in VCAM-1 vs. ICAM-1 expression. Representative images are from 2 independent experiments with 3 and 5 mice per group. E, Image based quantification of vascular ICAM

and VCAM expression. Graph depicts mean ± SD of cumulative data from 2 independent experiments (uninjured n = 6, d1 n = 10, **P < 0.01, Two-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak test). F, Scatter plot of

sum intensity of ICAM vs VCAM expression depicting the lack of a correlation between the two variables. Each dot represents a single mouse, and the graph is a representation of data points

shown in Extended Data Fig. 7e, (R2 = 0.089, P = 0.4, Pearson’s product moment correlation test). G, Scatter plot of ICAM vs. VCAM gene expression determined by qPCR in the brain 24 h

post-injury. No correlation was observed between the two variables. Each dot represents one mouse. Graphs depict cumulative data from 2 independent experiments with 5 mice per experiment,

(R2 = 0.000078, P = 0.98, Pearson’s product moment correlation test). Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 8 EFFECT OF MYELOMONOCYTIC CELLS ON CEREBRAL REPAIR AND ANGIOGENESIS. A, B, Confocal

microscopy of cerebral cortex 10 days after injury shows areas of gliosis (GFAP, blue) and microglia clustering (Iba-1, red) relative to tomato-lectin+ vasculature. Mice were treated

continuously with either isotype control (A) or αLFA1/VLA4 (B) antibodies. Continuous treatment with αLFA1/VLA4 results in large areas of brain tissue with blood vessels. Images are

representative of 5 mice per group. C, D, Flow cytometric analysis and gating strategy of monocyte and neutrophil depletion in blood (C) and brain (D) following continuous treatment with

αGR-1 and αLy6G antibodies 6 d post-injury compared to isotype treated controls. The following panel was used: Ly6C FITC, GR-1 BV421, CD11b BV570, Cx3CR1 BV711, P2RY12 PE, CD45 BUV395, Ly6G

BUV563, CD44 BUV737, CD115 APC and live/dead fixable blue cell staining kit. Plots were pre-gated for single, live cells and subsequently for CD45 + CD11b + cells. In brain samples gated,

microglia were identified as CD45lowCx3Cr1 + P2RY12 + CD44- cells. Monocytes were identified as CD45 + CD44 + CD115 + Ly6G-GR1low and neutrophils as CD45 + CD44 + CD115-Ly6G + GR1hi. In mice

treated with αLy6G, Ly6G was not used to characterize cells flow cytometrically. Moreover, in mice treated with αGR-1, GR-1 was not used to characterize the cells. Graphs show the mean ± SD

and are representative of 2 independent experiments with n = 5 (C) and n = 4 (D) mice per group (**P < 0.01, Two-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak test). E, F, Intravital microscopy of cerebral

vasculature and image-based quantification of vascular coverage in naïve B6 mice, CCR2 KO mice and CCR2 KO mice with CD115 + monocyte adoptive transfer 10 d post-injury. Adoptive transfer of

CD115 + monocytes from B6 mice partially reconstitutes the angiogenic process. Graph shows mean ± SD and is representative of two independent experiments with (n = 4 mice per group, **P

< 0.01, Kruskal-Wallis/Dunn’s test). Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 9 QPCR ANALYSIS OF GENES ENCODING FOR ANGIOGENESIS RELATED PROTEINS. qPCR analysis of genes encoding for angiogenesis

related proteins. Data from these experiments are represented in Fig. 4i. A, Volcano plot of angiogenesis related gene expression between uninjured mice and mice d6 after injury. B. Bar

graph of gene expression differences between injured and uninjured mice for genes with Q < 5%. C-D, Volcano plot of angiogenesis related gene expression after continuous αGr-1 (C) or

αLFA1/VLA4 administration (D). E-F, Bar graphs of gene expression difference for genes with Q < 5%. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4 mice per group. Statistical

analysis was performed using multiple t-tests and the Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli method to correct for the false discovery rate, with a desired Q value of 5%. Data are representative

of 2 independent experiments with 4 mice per group per experiment, source data in Supplementary Table 4. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 10 VEGF-EXPRESSING MICROGLIA ARE INVOLVED IN ANGIOGENESIS.

VEGF-expressing microglia are involved in angiogenesis. A, B, Intravital microscopy of cerebral vasculature 10 d after injury (A) and image-based quantification of vascular coverage (B) in

PLX5622 versus vehicle control treated mice show a lack of angiogenesis after microglia depletion. Blood vessels were labeled with EB (red) and tomato-lectin (green). Graphs depict mean ± SD

of cumulative data from 3 independent experiments (n = 16 mice per group, **P = 4e-13, two-tailed Student’s t-test). C, Volcano plot of angiogenesis related gene expression in vehicle vs.

PLX3397 treated (CSF1R inhibitor) mice 6 d post-injury D, Bar graph of gene expression difference for genes with Q < 5%. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4 mice

per group. Statistical analysis was performed using multiple t-test and the Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli method to correct for the false discovery rate, with a desired Q value of 5%. A

heatmap of the data from panels A and B is shown in Fig. 5b, source data in Supplementary Table 4. E, Representative heatmaps used to identify different immune cell populations following

high parameter flow cytometric analysis of the immune landscape in the cerebral cortex d1 and d6 following injury in Cx3cr1CreER/+ x Stopfl/+ TdTomato mice. The following panel was used:

Ly6C BB790, MHCII BV480, CD11b BV570, CD115 BV605, CD24 BV650, Cx3Cr1 BV711, CD11c BV785, P2RY12 PE, Ter-119 PE/Cy5, CD206 PE/Cy7, CD45 BUV395, CD4 BUV496, Ly6G BUV563, CD19 BUV661, CD44

BUV737, CD8 BUV805, F4/80 APC-R700, TCRβ APC/Cy7, VEGF-A AF647, TdTomato and live/dead fixable blue cell staining kit. Data were pre-gated on CD45 + Ter119- live cells, subsequently analyzed

using an unsupervised clustering algorithm to group data into subpopulations (PhenoGraph) and visualized using UMAP. Quantification of these experiments is provided in Fig. 5f. F, Gating

strategy for flow cytometry experiment demonstrating a lack of VEGF-A + microglia in mice treated with continuous αLFA1/VLA4 after injury. The following panel was used: CD24 FITC, CD11b

BV570, P2RY12 PE, TdTomato, CD45 BUV395, VEGF-A AF647 and live/dead fixable blue cell staining kit. Quantification of these experiments is provided in Fig. 5h,i and gating strategy in

Supplementary Fig. 1B. Source data SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Supplementary Fig. 1 and Table 1. REPORTING SUMMARY SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 2 Demographic data, symptoms,

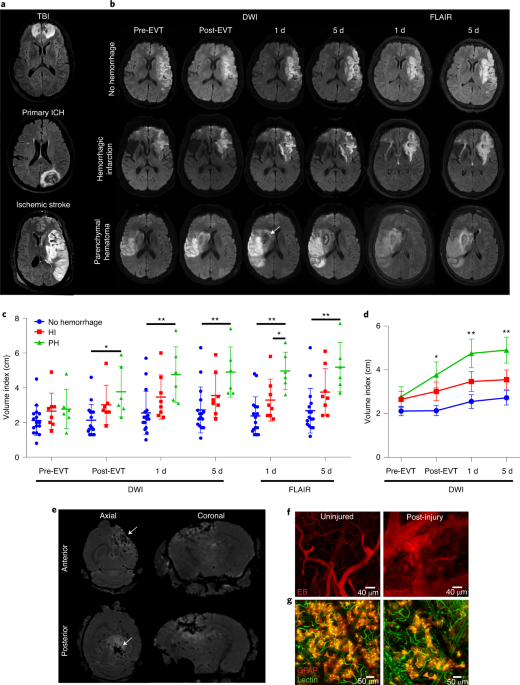

stroke characteristics and MRI imaging data from patients who had strokes. The MRI imaging data were used to generate the graphs in Fig. 1c,d. SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 3 Gene expression data used

to generate the heatmap in Extended Data Fig. 3g. ΔΔCt analysis was completed using _Gapdh_ as the housekeeping gene and contralateral hemisphere tissue as a control. Sheets 1 and 2 depict

independent experimental replicates. SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 4 Gene expression data used to generate heatmaps and bar graphs in Figs. 4i and 5b and Extended Data Figs. 9 and 10a,b. ΔΔCt analysis

was completed using _Gapdh_ as the housekeeping gene and uninjured tissue as a control. Sheets 1 and 2 depict independent experimental replicates. SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 5 RNA-seq data

analysis and IPA. RNA-seq results from cerebral cortex biopsies of uninjured mice versus injured mice at day 20 treated continuously for 10 d with αLFA1/VLA4 or isotype control antibodies

(data are presented in Fig. 6a–d, and methods are described in “RNA-sequencing data analysis” in the Methods). SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 6 RNA-seq. IPA of concordant dysregulated genes in

αLFA1/VLA4-treated mice relative to the other two groups, uninjured and control (data are presented in Fig. 6a–d, and methods are described in “RNA-sequencing data analysis” in the Methods).

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 7 Statistical analysis for graphs in Figs. 1c,d, 2d,g–i, 3c,e–i, 4b,d,f,h, 5a,d,f,h and 6e,f and Extended Data Figs. 2c–e,h, 3b,d,f,h, 6a,b–d, 7a–c,e–g, 8c,d,f and 10b.

SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 1 Vascular injury and leakage following transcranial sonication. Mice were injected with EB (red) i.v. immediately after anterior injury and were subsequently imaged for

40–60 min. The time lapse of the uninjured cortex depicts intact pial and parenchymal vessels. Following sonication, cerebral blood vessels (especially capillaries) were heavily injured,

resulting in leakage of EB into the brain parenchyma. Videos are representative of five mice per group. SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 2 Cerebrovascular injury results in edema. Representative

NG2-mEGFP mice were imaged before (uninjured) and after anterior injury (injured). Mice were injected i.v. with EB (red) immediately after injury and 1 min before imaging. NG2-mEGFP (green)

allows for visualization of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and mural cells, thus providing a stable brain structure upon which tissue distortion (edema) could be observed. The time lapse of

the injured cortex shows substantial tissue distortion resulting from edema (white dotted circle). This video represents two independent experiments with three mice each. SUPPLEMENTARY

VIDEO 3 Destruction of glia limitans following injury. GFAP-CreER ; Stopfl/+ TdTomato mice were injected i.v. with tomato lectin DyLight 488 (green) immediately after anterior injury and 1

min before imaging. The representative time lapse of the uninjured cortex shows surface-associated astrocytes (reddish yellow) comprising the glia limitans superficialis. These cells become

severely damaged and lose their fluorescence following ultrasound injury. This video is representative of two independent experiments with three mice per group. SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 4

Microglia form rosettes in response to cerebrovascular injury. Part 1, _Cx3cr1_GFP/+ (green) mice were injected with EB (red). Mice were imaged immediately after injury or starting 1 h after

injury. The representative time lapse of the uninjured cortex (left) demonstrates resting ramified microglia. Following anterior injury, microglia immediately project processes, creating

tube-like structures that compartmentalize blood vessels within ~20 min (middle). Within an hour, multiple tubular formations (rosettes) are visible (right). Part 2, a representative time

lapse from a _Cx3cr1_GFP/+ (green) mouse initiated immediately after injury shows the formation of rosettes within 20 min. Part 3, a representative time lapse from a _Cx3cr1_GFP/+ (green)

mouse injected i.v. with EB (red) and imaged at 24 h post-injury. At this time point, the rosette-forming microglia have transformed into phagocytic ameboid cells. Videos are representative

of two experiments with five mice per group. SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 5 Extensive BBB leakage following cerebrovascular injury in microglia-depleted mice. Representative videos from _Cx3cr1_GFP/+

(green) mice demonstrate the EB (red) extravasation assay with and without microglia depletion (that is, PLX3397 administration). Quantification of these time lapses is shown in Fig. 2c,d.

Naive and PLX3397-treated _Cx3cr1_GFP/+ mice were injected with EB i.v. immediately following anterior injury and were subsequently imaged for 40–60 min. Microglia depletion is associated

with significantly increased BBB leakage after cerebrovascular injury. Videos are representative of three experiments with four mice per group. SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 6 Purinergic receptor

signaling is responsible for microglial rosette formation. Representative time lapses from _Cx3cr1_GFP/+ (green) mice captured immediately after anterior injury show the effect of

transcranial P2RY12 or CX43 hemichannel inhibitors on microglial rosette formation. Vehicle was applied transcranially to the control group. Quantification of these time lapses is shown in

Fig. 2e,f. Both P2RY12 and CX43 inhibition impede the formation of microglia rosettes. Videos are representative of three independent experiments with three to five mice per group.

SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 7 Transcranial inhibition of CX43 hemichannels increases BBB leakage after cerebrovascular injury. Representative time lapses from _Cx3cr1_GFP/+ (green) mice captured

immediately after anterior injury show the extent of EB (red) leakage in the presence or absence of a transcranial CX43 hemichannel inhibitor. Quantification of these time lapses is shown in

Fig. 2g. CX43 inhibition impedes microglia rosette formation and enhances EB extravasation. Videos are representative of two independent experiments with three to six mice per group.

SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 8 Enhanced BBB leakage following cerebrovascular injury in GFAP-CreER-_Cx43_fl/fl mice. Part 1, representative time lapses show EB (red) leakage in WT littermate control

(that is, GFAP-CreER-_Cx43_fl/+) versus GFAP-CreER-_Cx43_fl/fl mice immediately following anterior injury. Quantification of these time lapses is shown in Fig. 2i. Enhanced extravasation of

EB is observed in GFAP-CreER-_Cx43_fl/fl mice. Part 2, representative time lapses from littermate control and GFAP-CreER-_Cx43_fl/fl mice after anterior injury show that EB is often confined

to a clot in control mice but leaks extensively into the surrounding parenchyma in GFAP-CreER-_Cx43_fl/fl mice. Videos are representative of two independent experiments with four mice per

group. SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 9 Cerebrovascular injury promotes massive extravasation of peripheral myelomonocytic cells. _LysM_GFP/+ mice were injected i.v. with tomato lectin DyLight 649

(red) immediately after anterior injury and imaged for 60–90 min. A representative time lapse shows massive infiltration of the brain parenchyma by LysM+ myelomonocytic cells (green) within

1 h of injury. Videos are representative of three experiments with two mice per experiment. SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 10 αLFA1/VLA4 antibodies prevent myelomonocytic cell infiltration into the

lesion core and perimeter. Intravital imaging of the lesion core and perimeter in _LysM_GFP/+ (green) mice that received a bolus treatment of αLFA1/VLA4 or isotype control antibodies

immediately after anterior injury. EB (red) was injected i.v. to label blood vessels. Representative time lapses from the lesion core (part 1) and perimeter (part 2) show that αLFA1/VLA4

impedes infiltration by LysM+ myelomonocytic cells. The time lapses were captured beginning at 30 min post-injury. Quantification of these time lapses is shown in Fig. 3e. Videos are

representative of two independent experiments with seven to eight mice per group. SOURCE DATA SOURCE DATA FIG. 1 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA FIG. 2 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA

FIG. 3 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA FIG. 4 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA FIG. 5 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA FIG. 6 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 2

Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 3 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 6 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 7 Source data for graphs

SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 8 Source data for graphs SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 10 Source data for graphs RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Mastorakos, P., Mihelson, N., Luby, M. _et al._ Temporally distinct myeloid cell responses mediate damage and repair after cerebrovascular injury. _Nat Neurosci_ 24, 245–258 (2021).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00773-6 Download citation * Received: 02 June 2020 * Accepted: 08 December 2020 * Published: 18 January 2021 * Issue Date: February 2021 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00773-6 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative