Linking organismal growth, coping styles, stress reactivity, and metabolism via responses against a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in an insect

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

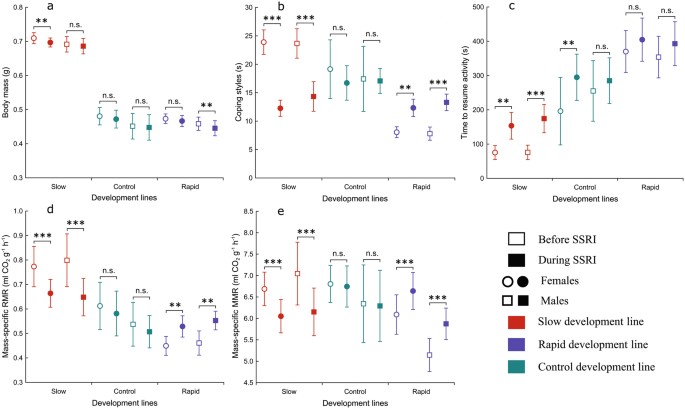

Evidence suggests that brain serotonin (5-HT) is one of the central mediators of different types of animal personality. We tested this assumption in field crickets Gryllus integer using a

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Crickets were selected for slow and rapid development and tested for their coping styles under non-stressful conditions (time spent exploring a

novel object). Resting metabolic rate, maximum metabolic rate and latency to resume activity were measured under stressful conditions (stress reactivity). Measurements were taken (i) before

and (ii) during the SSRI treatment. Before the SSRI treatment, a strong negative correlation was observed between coping style and stress reactivity, which suggests the existence of a

behavioral syndrome. After the SSRI treatment, the syndrome was no longer evident. The results of this study show that 5-HT may be involved in regulating behavior not only along a stress

reactivity gradient but also along a coping styles axis. The relationship between personality and the strength and direction of 5-HT treatment on observed behaviors indicates trait-like

individual differences in 5-HT signaling. Overall, these findings do not support recent ideas arising from the pace-of-life syndrome (POLS) hypothesis, which predict higher exploration and

metabolic rates in rapidly developing bold animals.

Phenotypic differences in trait expression are a prerequisite for evolution through natural selection. Although most of the traits of an organism vary around a mean value, research on human

and animal behavior has revealed between-individual clusters in behavioral responses, often attributed to different personality axes that are called personality types, behavioral

predispositions, temperaments or coping styles. Some of these behavioral responses are not heritable1,2, while others demonstrate a negligible or a considerable degree of

heritability3,4,5,6,7. Animal personality is tightly linked to individual life histories, survival and fitness5,6,8,9,10,11,12,13.

The pace-of-life syndrome (POLS) hypothesis, rooted in the classic concept of r- and K-selection, is particularly relevant in this context14,15,16, as it suggests that life history traits

such as age at maturity and growth rate are likely coupled with individually consistent behaviors and immune responses. For example, shy individuals often grow slower, reach larger body

size, mature later, invest more in immune system and have longer hiding time in an anti-predator context under familiar conditions than bold individuals16. Aggressiveness of bold individuals

hypothetically facilitates acquiring and monopolizing resources and may be linked to a fast growth rate and more intense reproductive effort early in life5,17.

Personality research is a complex field that adjoins behavioral ecology with psychology and molecular biology. It is therefore important to define key terms before testable hypotheses are

proposed. The term behavioral syndrome indicates that behavioral trait characteristics involve suites of correlated behaviors18,19 that are consistent over time and across contexts. The term

coping style is more commonly used to characterize individual trait differences in biomedicine, and this concept has been useful in explaining behavioral responses and their underlying

physiological mechanisms. The coping style concept implies that animals may react to a stimulus with alternative response patterns. According to the two-tier model of animal personality

proposed by Steimer et al.20, coping styles reflect the quality of the response to a stressor, while stress reactivity reflects the quantity of the response expressed. In this model, bold

individuals are those with a strong tendency to act (proactivity) combined with low stress reactivity. Docile individuals can be characterized as a combination of reactive coping associated

with low stress reactivity. The combination between high stress reactivity and a high tendency for proactive coping is labeled as panicky. Shy individuals exhibit reactive coping style and

high stress reactivity.

Although those personality characteristics are common, researchers rarely use all of the above terms because that would require the use of several tests for each individual being studied.

For example, stress reactivity needs to be measured by obtaining levels of stress hormones/neuromediator concentrations, or by observing the organisms under stressful conditions. In

contrast, reactive and proactive coping styles differ in behavioral flexibility, where the proactive individuals act on the basis of previous experiences and develop routines in stable

environments21,22. The reactively coping animal tends to rely more on a detailed appraisal of their current environment because they react to immediate environmental stimuli and tend to

explore any changes in their environment.

The metabolic rate of an organism varies with its body size and body temperature23,24. The POLS hypothesis proposes that rapidly developing, often bold individuals have life histories

involving high daily energy expenditures and higher basal or resting metabolic rates (RMR) because they are forced to process more food and inevitably excrete more waste products at a faster

rate compared to slowly developing individuals of same size. Rapidly developing individuals may, however, remain smaller than slow developers16. Thus, personality also has the potential to

affect the metabolic rate of an organism. Another important but often neglected source of variability in RMR arises because individuals consistently differ in their stress responses to

conditions in which metabolism measurements are performed25,26. For example, because reactive individuals (shy, docile) often become immobile under stressful conditions12,13, their metabolic

rates may be mistakenly classified as RMR27. Recent research shows that while the latency to resume body movements after handling in a familiar environment is longer for slowly developing

crickets, they resume body movements sooner than rapidly developing crickets when in a more stressful, unfamiliar environment28. Slowly developing crickets were found to have significantly

higher RMR compared to rapidly developing crickets. It is important to note that according to established experimental procedure, measurements of respiration always require placing an

organism in a novel environment27. This has the potential to induce significant stress, which may force less stress-resistant animals to stay active during respirometry to explore or escape

their respirometry chambers. This demonstrates the importance of finding the proper approach to measurements of stress reactivity and metabolism, as well as making a correct interpretation

of the results obtained to explain the relationships between animal personality and underlying physiological mechanisms29.

Behavioral responses of shy, often anxious individuals are associated with high concentrations of stress hormones30, implying that their slowness and caution are caused by physiological

stress. In psychology and physiology, shyness is usually defined as the feeling of anxiety and awkwardness when an individual is under conditions of stress. Stronger forms of shyness are

usually referred to as anxiety and elevated neuroticism. In extreme cases, it might be related to a depression-like psychological condition, which includes the experience of fear to the

extent of inducing panic31. This calls for reliable tests to discriminate between shy and panicky personality types20,29.

In the central nervous system, serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine: 5-HT), a monoamine neurotransmitter32, has several important functions, including the regulation of aggression, mood, sleep,

dispersal and metabolic rate33,34,35,36. Modulation of serotonin at synapses of the brain is thought to be the key mechanism of several classes of pharmacological antidepressants.

Experimental evidence has revealed links between low levels of 5-HT and the development of anxiety and stress-prone behavioral phenotypes37,38. However, an association between low

concentrations of 5-HT and proactive coping style39 suggests that 5-HT may be involved in the regulation of behavior not only along the stress reactivity gradient but also along the coping

styles axis20,29,40 (but see34). These findings indicate that 5-HT potentially affects personality types in a more complex way, which should be taken into account when testing the influence

of pharmacological compounds on behavioral responses under stress.

Field crickets are a suitable and often-used model group for animal personality research41,42,43. In this study, we compared coping style differences between slowly and rapidly developing

western stutter-trilling crickets (Gryllus integer) under non-stressful and stressful conditions. Prior to the study, the crickets had been selected for slow and rapid developmental time

over five generations. We also measured their RMR, maximum metabolic rate (MMR) and the latency to resume activity under stressful conditions in the insect chamber of respirometer. This was

done twice: before a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) was added to the food and once again during the anti-depressant treatment.

We expected greater effects of anti-depressant treatment on behavioral responses of proactive individuals (bold, panicky) − those paying little attention to minor changes in their

environment. Although some earlier evidence suggested that central injection of 5-HT or its precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) may cause increased metabolic rates44,45 (but see46), other

research has shown that serotonin deficiency significantly increases amino acid, energy, purine, lipid and gut microflora metabolisms and rates of oxidative stress47,48,49. Therefore, we

predicted an SSRI-induced decrease in the metabolic rate of crickets with high stress reactivity (shy, panicky), especially in panicky individuals50,51, because 5-HT is likely to influence

proactive individuals (panicky, bold) more than reactive ones (shy, docile)36,52.

Our results demonstrate that SSRI can have relatively small but significant effects on body mass of crickets (rmANOVA, F(1, 100) = 22.27, P