Internal tides can provide thermal refugia that will buffer some coral reefs from future global warming

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Observations show ocean temperatures are rising due to climate change, resulting in a fivefold increase in the incidence of regional-scale coral bleaching events since the 1980s;

analyses based on global climate models forecast bleaching will become an annual event for most of the world’s coral reefs within 30–50 yr. Internal waves at tidal frequencies can regularly

flush reefs with cooler waters, buffering the thermal stress from rising sea-surface temperatures. Here we present the first global maps of the effects these processes have on bleaching

projections for three IPCC-AR5 emissions scenarios. Incorporating semidiurnal temperature fluctuations into the projected water temperatures at depth creates a delay in the timing of annual

severe bleaching ≥ 10 yr (≥ 20 yr) for 38% (9%), 15% (1%), and 1% (0%) of coral reef sites for the low, moderate, and high emission scenarios, respectively; regional averages can reach twice

as high. These cooling effects are greatest later in twenty-first century for the moderate emission scenarios, and around the middle twenty-first century for the highest emission scenario.

Our results demonstrate how these effects could delay bleaching for corals, providing thermal refugia. Identification of such areas could be a factor for the selection of coral reef marine

protected areas. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE METEOROLOGICAL DRIVERS OF MASS CORAL BLEACHING ON THE CENTRAL GREAT BARRIER REEF DURING THE 2022 LA NIÑA Article Open access 12

October 2024 DRIVERS OF MARINE HEATWAVES IN CORAL BLEACHING REGIONS OF THE RED SEA Article Open access 18 February 2025 HIDDEN HEATWAVES AND SEVERE CORAL BLEACHING LINKED TO MESOSCALE EDDIES

AND THERMOCLINE DYNAMICS Article Open access 06 January 2023 INTRODUCTION One of the major causes of mass coral reef bleaching events worldwide is rising sea temperatures caused primarily

by anthropogenic global warming1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Bleaching can occur when corals that are exposed to sustained temperatures above their average annual ranges expel their symbiotic algae.

Although it is possible for bleached corals to recover, this process can take many years or decades and the recovered reefs will likely have initially reduced species diversity with fewer

reef-building coral species9,10,11. When these bleaching events occur annually, it is unlikely that heat-sensitive coral species can survive, as this frequency of bleaching does not give the

corals sufficient time to recover12,13. Remotely sensed sea surface temperatures (SSTs) have been used as a tool for monitoring the global ocean for anomalously high temperatures and

evaluating current and potential future bleaching threats. The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Coral Reef Watch (CRW) program (https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov)

developed a coral bleaching monitoring and prediction system based on satellite SST measurements, modeling, and in situ measurements14. Accumulating heat stress is quantified using

degree-heating weeks (DHW) and severe bleaching conditions have been correlated with DHW > 8 °C-weeks15. More recently, Global Climate Model (GCM) projections of SST have been used to

predict when different regions will start to experience severe coral bleaching often enough that they will not recover, finding that with “business as usual” emissions16,17 (RCP8.5),

bleaching as modeled using accumulated heat stress via DHW will become an annual event for most of the world’s coral reefs within 30–50 yr3,4,18,19. One critical source of uncertainty in

such projections is the large difference between the horizontal scale of individual coral reefs (101–104 m) and the scale of coupled atmosphere–ocean GCMs used to project future

climate16,17,18 (104–105 m). In addition to the disparity in spatial resolution of the GCMs relative to the scales of reef communities, this coarse spatial and temporal resolution cannot

capture meso- and sub-mesoscale processes that can also affect the exposure of corals to anomalous temperatures, such as upwelling, diurnal heating, eddies, and internal waves. Many of these

processes lead to strong vertical thermal gradients, whereby the ocean temperature near the benthic substrate, where the corals reside, is cooler than at the surface. In particular,

internal waves at the tidal frequency and greater can advect deeper, cooler (~ °C) waters up (~ 10 s–100 s m vertically and ~ 100 s–1000 s m horizontally) into shallower-water environments.

These features have been shown to occur over shallow-water, hermatypic (0–40 m depths) coral reefs worldwide20,21,22,23,24,25. Because internal waves regularly flush reefs with cooler

waters, they can modify species assemblages25, reduce thermal stress26,27,28,29 and corals’ susceptibility to bleaching30. The bleak outlook on coral reef futures underscores the importance

of identifying places where processes that buffer the thermal stress from rising SSTs may serve as thermal refugia. Here, we present the first attempt to quantify the effects internal wave

processes might have on moderating future thermally induced bleaching for coral reefs globally. We quantify the spatial and vertical patterns of semi-diurnal internal waves’ influence on

water temperatures over coral reefs, determine how those patterns will vary in the future for different climate-change scenarios, and discuss how such information may be incorporated into

the decision-making process for designating Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) for coral reef protection and preservation. MATERIALS AND METHODS Semidiurnal temperature fluctuations were

constructed using past climatology of ocean vertical thermal structure coupled with a global dataset of semidiurnal internal tide amplitudes; they were then applied to projected SSTs for

different climate change scenarios. Here, “semidiurnal” is used to mean the principal lunar (M2; period ~ 12.42 h) and the principal solar (S2; period ~ 12.00 h) semidiurnal tidal

constituents. We note that, because we lack full water-column temperature, we cannot delineate barotropic from baroclinic semidiurnal internal tide driven temperature variability; as such,

we refer to these patterns as “semidiurnal temperature fluctuations.” The objective of our analyses was to allow for direct comparison with the findings of van Hooidonk et al.18. Details are

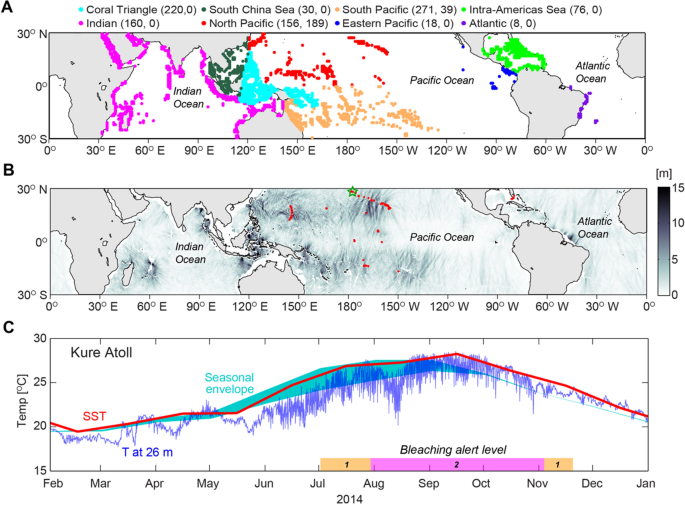

provided below on the model and observational datasets used in the analyses. MODEL OF SEMIDIURNAL TEMPERATURE FLUCTUATIONS The global coral reef locations (1° × 1° pixels) were obtained

from the merged reefbase/UNEP-WCMC and Millennium Coral Reef Mapping Project reefs database (https://imars.usf.edu/MC/index.html). For each coral reef location (1° × 1° pixel), we found the

monthly climatology of vertical ocean temperature using the Argo float dataset31. These data are collected and made freely available by the International Argo Program and the national

programs that contribute to it (https://www.argo.ucsd.edu, https://argo.jcommops.org). The Argo Program is part of the Global Ocean Observing System. The Roemmich-Gilson Argo climatology

(https://sio-argo.ucsd.edu/RG_Climatology.html) provides a gridded, optimally interpolated, upper-ocean temperature climatology and monthly anomaly field32 that continues to be updated; the

data utilized here were for 2004–2016, with 58 vertical steps down to 2000 dbar. Next, a corresponding internal tide amplitude was found for each coral reef site using a global open-ocean

mode-1 M2 and S2 internal tide dataset provided by Zhao et al.33. These amplitudes were computed based on sea surface height (SSH) measurements from multiple satellites. These observations

only capture the coherent internal tide, missing the incoherent component, which may constitute 30–50% additional internal tide energy, especially close to the equator34. To partially

account for this missing energy, the M2 and S2 amplitudes were increased by 30%. The associated semidiurnal internal tide amplitude used for each site was the mean within a 1° × 1° box

centered on each coral reef pixel. Only pixels that contained at least 25% non-empty internal tide amplitude observations were used; this criterion allowed for 52% of the global coral sites

(compare sites shown in Figs. 1a, 2b). Coral sites that lack internal tide amplitude information are primarily locations on broad continental shelves, such as those around Florida, USA, and

the Bahamas, the Sunda shelf in Southeast Asia, the Arafura Shelf between Australia and Papua New Guinea, and the Red Sea. We also note that open-ocean internal tides can amplify as they

propagate from deep to shallow waters, sometimes inducing internal solitary waves that pump cooler-deeper waters towards the surface35. Thus, these internal tide amplitudes likely represent

an underestimation of the vertical internal motions in the nearshore. The temperature decrease caused by the semidiurnal fluctuations was identified in the Argo monthly climatology as the

difference between the SST and the temperature at a depth equal to the coral’s depth plus the internal tide amplitude for that location. Three coral reef depths were considered: 10, 20, and

30 m. The monthly temperature decrease was interpolated to 12-h intervals, and the yearly semidiurnal temperature fluctuation model pattern was this temperature decrease alternating with

zero temperature decrease from SST. In the natural environment, nearshore internal waves do not necessarily result in thermal swings that approach sea surface values; often, their maximum

temperatures are less than SSTs. In this respect, our model could be considered a conservative representation of potential cold-water exposure due to semidiurnal internal tides. PROJECTED

SEA-SURFACE TEMPERATURE The modeled semidiurnal temperature fluctuations for the global coral reef sites were applied to projected global SST timeseries from Van Hooidonk et al.18. These SST

projections were taken from the World Climate Research Programme’s CMIP5 datase5 (see van Hooidonk et al.18 for complete table), and here we focus on the projected SST from three

Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) emission scenarios16,17: (1) RCP4.5, which is stabilization without overshoot, (2) RCP6.0, which is stabilization at a higher radiative forcing

without overshoot), and (3) RCP8.5, which is fossil-fuel aggressive (i.e., baseline scenario). For each pixel, the projected SST time series was adjusted such that the 2006–2011 model mean

was equal to the mean of the corresponding 1985–2005 Pathfinder SST (see section below). In addition, the annual cycles were replaced with those from the observed Pathfinder climatology.

Missing pixels near the coasts were filled using a Poisson relaxation interpolation. MODEL EVALUATION The modeled semidiurnal temperature fluctuations were compared to 225 subsurface, in

situ, long-term temperature records collected at coral reef sites across the Pacific Ocean and Florida (Fig. 1a; see Supplementary Table S1 online). These subsurface data came from two

sources: (1) the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center Coral Reef Ecosystem Program, made available through the National Coral

Reef Monitoring Program36 (https://data.nodc.noaa.gov), and (2) the Coral Reef Research Foundation (https://coralreefpalau.org) long-term monitoring program around Palau. The locations of

these measurements were primarily from fore reefs in depths between 10 to 30 m, and were from 47 distinct islands, atolls, submerged reefs, and coastal areas. Sites within lagoons and/or

located > 5 km from the 50-m isobaths (i.e., a broad shelf separating them from the open ocean) were excluded. Temperatures were measured at intervals ranging from every 5 min to hourly

and each record had a length of at least 2 yr (maximum length was 6.2 yr, mean = 2.2 yr). The corresponding SST time series for each site location and record time period were found using the

Pathfinder Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) v4.1 + Global Area Coverage (GAC) monthly temperature (see Supplementary Table S1 online). This global SST has a 0.1° × 0.1°

resolution and is available from the NOAA OceanWatch Central Pacific Node website (https://oceanwatch.pifsc.noaa.gov/). At each of these in situ sites, the subsurface temperature was

band-pass filtered (9.6–14.4 h) and the largest temperature decrease from SST was identified and compared to that from the modeled fluctuations (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). There was

a robust linear correlation (_r_ = 0.81, _p_ ≪ 0.05, _df_ = 186) between the observed and the modeled maximum subsurface temperature, with a slope close to 1 (_m_ = 1.3) and an offset of

0.5. Thus, the modeled and observed maximum subsurface temperature decrease roughly scale together and this linear regression was used to adjust the modeled time series for each global coral

reef location. YEAR OF ANNUAL SEVERE BLEACHING (YASB) Within the projected temperature time series, bleaching was defined using the degree-heating-weeks (DHW) metric37. As in van Hooidonk

et al.18, DHW start to accumulate when projected temperatures exceed the maximum monthly mean (MMM) from the pathfinder climatology. Here, the MMM for each coral location is adjusted for the

three considered depths (10, 20, and 30 m) using the mean temperature change with depth from the Argo climatology; this was done under the assumption that corals at deeper depths have

reduced thermal tolerance. Severe bleaching with high mortality have been observed to occur when DHW > 8 °C-weeks14,15. For a coral reef site, the Year of Annual Severe Bleaching (YASB)

is defined as the projected year when severe bleaching starts to occur at least once a year, for 10 consecutive yr18. RESULTS Per van Hooidonk et al.18, the YASB can be considered the

“tipping point” for a coral reef, a conservative estimate of when recovery from consecutive bleaching events will no longer be possible. Here we use the RCP6.0 scenario as a baseline to

compare and contrast the two end-member scenarios (RCP4.5 with drastic emission cuts and the RCP8.5 with unabated emission growth). With RCP6.0, using SST alone, 69% of coral reef sites with

a corresponding internal tide amplitude are projected to reach YASB before 2091 (see Supplementary Fig. S2 online). Of these coral reef sites, imposing the effects of semidiurnal,

internal-tide driven temperature fluctuations on the projected SST creates a delay in the timing of YASB (∆YASB) of ≥ 10 yr for 12–17% of sites, depending on depth, and ∆YASB ≥ 20 yr for up

to 1% of sites (Fig. 2). Under a low emissions scenario (RCP4.5), ∆YASB afforded by the semidiurnal temperature fluctuations is greater, with 30–44% of sites experiencing a delay ≥ 10 yr and

8–10% of the sites experiencing a ∆YASB ≥ 20 yr. Under a high emissions scenario (RCP8.5), a ∆YASB ≥ 10 yr only transpires for up to 1% of sites at 20 m depth and no sites experiencing a

∆YASB ≥ 20 yr. Previous studies3,4,18,19 have projected the vast majority of reefs to experience annual bleaching by the mid twenty-first century for high emission scenarios such as RCP8.5.

Our results indicate that when considering exposure to semidiurnal temperature fluctuations, this prediction does not change, except for a small subset of sites. The thermal benefit (i.e.,

subsurface cooling causing a delay in YASB) provided by semidiurnal temperature fluctuations changes across the different emission scenarios. Across all water depths, the greatest thermal

benefit occurs for the low emission (RCP4.5) than the high emission (RCP8.5) scenario, for the cooling benefit is not enough to offset the additional thermal stress at the highest projected

SSTs later in the century (Fig. 3). Across reefs, the most extensive thermal buffering for all emission scenarios is projected for the shallowest (10 m) reef sites. This likely occurs

because they have relatively high thermal tolerances due to their proximity to higher surface temperature variability but receive cooling benefits from the subsurface temperature

fluctuations. Interestingly, the contribution of semidiurnal fluctuations to cooling is greatest later in the century for the RCP4.5 and 6.5 scenarios, but for RCP8.5 it peaks during the

middle of the century, followed by a decline. This is because, as the number of coral reef sites reaching their YASB rapidly increases, even a small ∆YASB during the middle of the century

results in a relatively large effect. Deeper corals experience temperatures cooler than SST, however, the degree of this cooling for a given depth depends on ocean vertical structure and, in

particular, the depth of the seasonal thermocline. A shallow seasonal thermocline coupled with large internal wave amplitudes can produce the greatest thermal benefit (cooling). Although

the number of coral reef sites in each geographic region varies, the projections generally indicate less thermal benefit to corals from semidiurnal internal tide activity in the Eastern

Pacific Ocean, South China Sea, and Intra-Americas Seas, as compared to the Indian Ocean, North and South Pacific Oceans, and Coral Triangle (Fig. 4). The higher benefit in the latter

regions is due to a shallow seasonal thermocline coupled with exposure to greater semidiurnal internal tide energy (Fig. 1). For all regions and across all depths, the thermal benefits

provided by depth and semidiurnal temperature fluctuations decreases substantially with increasing emission scenario (Fig. 4). The Indian Ocean, Coral Triangle, North Pacific, and South

Pacific are the geographic regions with coral reef sites that both have a corresponding internal tide amplitude and an SST YASB before 2091. Of these four regions, the Indian Ocean has the

highest percentage of reef sites with delays ≥ 10 yr under all emissions scenarios. DISCUSSION The results presented here demonstrate how the influence of semidiurnal internal tides could

act to delay thermally induced bleaching for pockets of reefs across the global ocean. There are a number of other sub-mesoscale processes that also drive upwelling of cooler waters onto

coral reefs that are not captured here. As a result, the projections provided here are relatively conservative and likely underrepresent the importance of such subsurface hydrodynamic

processes to provide thermal refugia and, thus, provide time to allow corals to adapt, either on their own or via human intervention, to the warming oceans. In addition, it remains unclear

how water column structure and subsurface cooling processes, including internal tide energetics, will be modulated by to climate change due to likely changes in surface versus subsurface

heating38,39 and mixing by projected changes in wind and ocean surface waves40. The Coral Triangle encompasses the majority of sites predicted to have ≥ 10 yr and ≥ 20 yr delays in YASB due

to semidiurnal temperature fluctuations alone, particularly in the Indonesian Seas. Satellite surveys indicate the Indonesian Seas have an exceptionally high prevalence of internal waves,

due to the large number of interisland sills that separate deeper basins coupled with year-round stratification41,42. In addition, the Coral Triangle has the world's highest levels of

marine biodiversity and over 500 species of reef-building coral43. Under RCP8.5, most of the considered Coral Triangle sites are predicted to reach YASB before 2091, but for corals at 10 m,

the combined effects of depth and the semidiurnal temperature fluctuations can delay the onset of annual severe bleaching by 1–2 decades. Thus, the high species diversity, coupled with

cooling driven by internal waves, underscores the potential of the Coral Triangle to serve as refugia for corals under increasing SST. Increasingly, MPAs have been used as a management tool

for protecting coral reefs around the globe44. The locations chosen for most MPAs were established based on criteria such as specific coral species of concern, coral ecosystem biodiversity,

and socio-economic drivers45. MPAs have been generally used to address local threats to coral reefs such as overfishing or land-based pollution and not the threat of thermally induced coral

bleaching, as increasing global sea temperatures are not something that local managers can control. MPAs will not be protected from increasing ocean temperatures unless a location is chosen

that experiences natural thermal buffering. Because thermally induced coral bleaching2 is projected to increase in both magnitude and frequency, research can help identify natural refugia

from thermal stress to aid the decision-making process46,47 of resource managers designating MPAs with the goal to protect and preserve corals, especially if emissions continue to track the

high-end RCP8.5 scenario. Identification of such areas would help provide additional time for managers to conduct interventions and coral reefs to adapt. In order to improve predictions of

the magnitude and location of internal tide cooling effects on coral reefs, a number of improvements in our understanding of fine-scale baroclinic processes must occur. For example, the

processes, timescales, and spatial scales over which internal tide energy translates from the open ocean to nearshore environments must be better constrained. As the resolution of coupled

atmosphere–ocean GCMs used to project future climate improves, they might better capture the effects of climate change on global internal tide energetics and how they drive local-scale

cooling of reefs may change in the future. As more detailed observation or models of those processes become available, they could be incorporated into the analyses provided here to better

constrain the influence of such processes to buffer increasing ocean temperatures. The synergistic effects of water-column structure and internal wave energy described here provide an

improved understanding of where, and to what extent, internal tidal motions might provide beneficial cooling to coral reefs around the globe for different emission scenarios. The buffering

effects of such motions are greater and occur later in the twenty-first century for lower emission scenarios than for the high-end scenario. Incorporation of information on how global carbon

emission scenarios may affect these processes that help buffer coral reefs from projected thermally induced bleaching will support the planning and management necessary to protect and

preserve coral reefs in the face of climate change. DATA AVAILABILITY The datasets analyzed during the current study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information

files). REFERENCES * Heron, S. F., Maynard, J. A., van Hooidonk, R. & Eakin, C. M. Warming trends and bleaching stress of the world’s coral reefs 1985–2012. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 38402 (2016).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hughes, T. P. _et al._ Spatial temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. _Science_ 359, 80–83 (2018).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. _Mar. Freshw. Res._ 50, 839–866 (1999). Google

Scholar * Donner, S. D., Skirving, W. J., Little, C. M., Oppenheimer, M. & Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Global assessment of coral bleaching and required rates of adaptation under climate change.

_Glob. Change Biol._ 11, 2251–2265 (2005). Article ADS Google Scholar * Goreau, T. J. & Hayes, R. Coral bleaching and ocean “hot spots.”. _Ambio_ 23, 176–180 (1994). Google Scholar

* Veron, J. E. N. _et al._ The coral reef crisis: the critical importance of <350 ppm CO2. _Mar. Pollut. Bull._ 58(10), 1428–1436 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Eakin, C.

M., Lough, J. M. & Heron, S. F. Climate variability and change: monitoring data and evidence for increased coral bleaching stress. In _Coral Bleaching: Patterns, Processes, Causes and

Consequences_ (eds Van Oppen, M. J. H. & Lough, J. M.) 41–67 (Springer, Berlin, 2009). Chapter Google Scholar * Couch, C. _et al._ Mass coral bleaching due to unprecedented marine

heatwave in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (Northwestern Hawaiian Islands). _PLoS ONE_ 12(9), e0185121 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Glynn, P.

W. Coral reef bleaching: facts, hypotheses and implications. _Glob. Change Biol._ 2, 495–509 (1996). Article ADS Google Scholar * Wilkinson, C. _Coral Reefs of the World: 2008_ (Global

Coral Reef Monitoring Network and Reef and Rainforest Research Centre, Townsville, 2008). Google Scholar * Grottoli, A. G. _et al._ The cumulative impact of annual coral bleaching can turn

some coral species winners into losers. _Glob. Change Biol._ 20(12), 3823–3833 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Schoepf, V. _et al._ Annual coral bleaching and the long-term recovery

capacity of coral. _Proc. Biol. Sci._ 282, 1887 (2015). Google Scholar * Hughes, T. P. _et al._ Global warming impairs stock-recruitment dynamics of corals. _Nature_ 568, 387–390 (2019).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Strong, A. E., Arzayus, F., Skirving, W. & Heron, S. F. Chapter 9: Identifying coral bleaching remotely via Coral Reef Watch—improved

integration and implications for climate change. In _Coral Reefs and Climate Change: Science and Management_ (eds Phinney, J. T. _et al._) (American Geophysical Union, Washington, DC, 2006).

Google Scholar * Kayanne, H. Validation of degree heating weeks as a coral bleaching index in the northwestern Pacific. _Coral Reefs_ 36, 63–70 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar *

Moss, R. H. _et al._ The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. _Nature_ 463, 747–756 (2010). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * van Vuuren, D.

_et al._ How well do integrated assessment models simulate climate change?. _Clim. Change_ 104(2), 255–285 (2011). Article ADS Google Scholar * van Hooidonk, R., Maynard, J. A. &

Planes, S. Temporary refugia for coral reefs in a warming world. _Nat. Clim. Change_ 3, 1–4 (2013). Article Google Scholar * van Hooidonk, R. _et al._ Local-scale projections of coral reef

futures and implications of the Paris Agreement. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 33966 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wolanski, E. & Pickard, G. L. Upwelling by internal tides and Kelvin waves

at the continental shelf break on the Great Barrier Reef. _Aust. J. Mar. Res._ 34, 65–80 (1983). Article Google Scholar * Wolanski, E. & Delesalle, B. Upwelling by internal waves,

Tahiti, French Polynesia. _Cont. Shelf Res._ 15, 357–368 (1995). Article ADS Google Scholar * Novozhilov, A. V., Chernova, Y. N., Tsukurov, I. A., Densivo, V. A. & Propp, L. N.

Characteristics of oceanographic processes on reefs of the Seychelles Islands. _Atoll Res. Bull._ 366, 1–36 (1992). Article Google Scholar * Leichter, J. J., Wing, S. R., Miller, S. L.

& Denny, M. W. Pulsed delivery of subthermocline water to Conch Reef (Florida Keys) by internal tidal bores. _Limnol. Oceanogr._ 41, 1490–1501 (1996). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

* Storlazzi, C. D. & Jaffe, B. E. The relative contribution of processes driving variability in flow, shear, and turbidity over a fringing coral reef: West Maui, Hawaii. _Estur. Coast

Shelf Sci._ 77(4), 549–564 (2008). Article ADS Google Scholar * Roder, C. _et al._ Metabloic plasticity of the corals _Porites lutea_ and _Diploastrea helipora_ exposed to large amplitude

internal waves. _Coral Reefs_ 30(1), 57–69 (2011). Article ADS Google Scholar * Storlazzi, C. D., Field, M. E., Cheriton, O. M., Presto, M. K. & Logan, J. B. Rapid fluctuations in

flow and water-column properties in Asan Bay, Guam: implications for selective resilience of coral reefs in warming seas. _Coral Reefs_ 32, 949–961 (2013). Article ADS Google Scholar *

Wall, M. _et al._ Large-amplitude internal waves benefit corals during thermal stress. _Proc. R. Soc. B_ 282, 20140650 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Schmidt, G. M., Wall, M., Taylor,

M., Jantzen, C. & Richter, C. Large-amplitude internal waves sustain coral health during thermal stress. _Coral Reefs_ 35, 869–881 (2016). Article ADS Google Scholar * Wyatt, A. S. J.

_et al._ Internal waves mitigate heat accumulation on coral reefs. _Nat. Geosci._ 13, 28–34 (2020). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Safaie, A. _et al._ High frequency temperature

variability reduces the risk of coral bleaching. _Nat. Commmun._ 9, 1671 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Argo. Argo float data and metadata from Global Data Assembly Centre

(Argo GDAC). SEANOE. https://doi.org/10.17882/42182 (2000). * Roemmich, D. & Gilson, J. The 2004–2008 mean and annual cycle of temperature, salinity, and steric height in the global

ocean from the Argo Program. _Prog. Oceanogr._ 82, 81–100 (2009). Article ADS Google Scholar * Zhao, Z., Alford, M. H., Girton, J. B., Rainville, L. & Simmons, H. L. Global

observations of open-ocean mode-1 M2 internal tides. _J. Phys. Oceanogr._ 46, 1657–1684 (2016). Article ADS Google Scholar * Zaron, E. D. Mapping the nonstationary internal tide with

satellite altimetry. _J. Geophys. Res. Oceans_ 122, 539–554 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar * Lamb, K. G. Internal wave breaking and dissipation mechanisms on the continental

slope/shelf. _Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech._ 46(1), 231–254 (2014). Article ADS MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Hoeke, R. K. _et al._ Coral reef ecosystem integrated observing system: in-situ

oceanographic observations at the US Pacific islands and atolls. _J. Oper. Oceanogr._ 2(2), 3–14 (2009). Google Scholar * Liu, G., Strong, A. E., Skirving, W. J. & Arzayus, L. F.

Overview of NOAA coral reef watch program’s near-real-time satellite global coral bleaching monitoring activities. In _10th International Coral Reef Symposium_, 1783–1793 (2006) * DeCarlo,

T. M., Karnauskas, K. B., Davis, K. A. & Wong, G. T. F. Climate modulates internal wave activity in the Northern South China Sea. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 42, 831–838 (2015). Article ADS

Google Scholar * Zhao, Z. Internal tide oceanic tomography. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 42, 9157–9164 (2016). Article ADS Google Scholar * Shope, J. B., Storlazzi, C. D., Erikson, L. H. &

Hegermiller, C. A. Changes to extreme wave climates of islands within the Western Tropical Pacific throughout the 21st century under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5, with implications for island

vulnerability. _Glob. Planet. Change_ 141, 25–38 (2016). Article ADS Google Scholar * Susanto, R. D., Mitnik, L. & Zheng, Q. Internal waves observed in the Lombok Strait.

_Oceanography_ 18, 80–87 (2005). Article Google Scholar * Jackson, C. Internal wave detection using the moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS). _J. Geophys. Res._ 112,

C11012 (2007). Article ADS Google Scholar * Briggs, J. C. The marine East Indies: diversity and speciation. _J. Biogeogr._ 32, 1517–1522 (2005). Article Google Scholar * Burke, L.,

Reytar, K., Spalding, M. & Perry, A. _Reefs at risk, revisited_ (World Resources Institute, Washington, DC, 2011). Google Scholar * Keppel, G. & Kavousi, J. Effective climate change

refugia for coral reefs. _Glob. Change Biol._ 21, 2829–2830 (2015). Article ADS Google Scholar * Cacciapaglia, C. & van Woesik, R. Reef-coral refugia in a rapidly changing ocean.

_Glob. Change Biol._ 21, 2272–2282 (2015). Article ADS Google Scholar * Turner, B. L. _et al._ A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._

100, 8074–8079 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was funded by the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Coastal and Marine Hazards and

Resources Program and NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program in support of the goals of the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force to protect and preserve coral reefs. We are grateful to Pat Colin for

the Coral Reef Research Foundation datasets. The data used to generate the results can be found at: https://doi.org/10.5066/P9PFGYMX. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for

descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Coastal and Marine Science

Center, 2885 Mission Street, Santa Cruz, CA, 95060, USA Curt D. Storlazzi & Olivia M. Cheriton * Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, University of Miami, Miami, FL,

33149, USA Ruben van Hooidonk * Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 98105, USA Zhongxiang Zhao * King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Red Sea

Research Center, Thuwal, Saudi Arabia Russell Brainard Authors * Curt D. Storlazzi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Olivia M. Cheriton

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ruben van Hooidonk View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* Zhongxiang Zhao View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Russell Brainard View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS C.D.S and O.M.C. designed the research; C.D.S. and O.M.C. carried out the research; O.M.C. and C.D.S. conducted the analyses; C.D.S., O.M.C., R.v.H.,

Z.Z., and R.B. wrote the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Curt D. Storlazzi. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to

the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Storlazzi, C.D., Cheriton, O.M., van Hooidonk, R. _et al._ Internal tides can provide thermal refugia that will buffer some coral reefs from future global warming. _Sci

Rep_ 10, 13435 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70372-9 Download citation * Received: 16 January 2020 * Accepted: 23 July 2020 * Published: 10 August 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70372-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative