Wafer scale synthesis of organic semiconductor nanosheets for van der waals heterojunction devices

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Organic semiconductors (OSC) are widely used for consumer electronic products owing to their attractive properties such as flexibility and low production cost. Atomically thin

transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are another class of emerging materials with superior electronic and optical properties. Integrating them into van der Waals (vdW) heterostructures

provides an opportunity to harness the advantages of both material systems. However, building such heterojunctions by conventional physical vapor deposition (PVD) of OSCs is challenging,

since the growth is disrupted due to limited diffusion of the molecules on the TMD surface. Here we report wafer-scale (3-inch) fabrication of transferable OSC nanosheets with thickness down

to 15 nm, which enable the realization of heterojunction devices. By controlled dissolution of a poly(acrylic acid) film, on which the OSC films were grown by PVD, they can be released and

transferred onto arbitrary substrates. OSC crystal quality and optical anisotropy are preserved during the transfer process. By transferring OSC nanosheets (p-type) onto prefabricated

electrodes and TMD monolayers (n-type), we fabricate and characterize various electronic devices including unipolar, ambipolar and antiambipolar field-effect transistors. Such vdW p-n

heterojunction devices open up a wide range of possible applications ranging from ultrafast photodetectors to conformal electronics. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS HETEROEPITAXY OF

SEMICONDUCTING 2H-MOTE2 THIN FILMS ON ARBITRARY SURFACES FOR LARGE-SCALE HETEROGENEOUS INTEGRATION Article 15 August 2022 HETEROGENEOUS INTEGRATION OF SINGLE-CRYSTALLINE RUTILE NANOMEMBRANES

WITH STEEP PHASE TRANSITION ON SILICON SUBSTRATES Article Open access 18 August 2021 ON-LIQUID-GALLIUM SURFACE SYNTHESIS OF ULTRASMOOTH THIN FILMS OF CONDUCTIVE METAL–ORGANIC FRAMEWORKS

Article 28 March 2024 INTRODUCTION Heterojunctions based on organic semiconductors (OSCs) and monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (ML TMDs), exploiting the advantages of both material

systems, attract interest in the engineering of electronic, photonic and optoelectronic devices1,2,3. OSC exhibit excellent electronic properties which can outperform or act complementary

to inorganic semiconductors4,5,6. OSC based electronic and optoelectronic devices such as organic light-emitting diodes (OLED)7 are already used as constituents of several consumer products

widely, especially in displays of television sets and mobile phones. ML TMDs are known for their superior electronic transport properties and have been identified as promising candidates for

ultrathin device technologies8,9. The combination of OSCs and high-performance ML TMDs provides novel opportunities for complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) technology10,11.

However, integration of OSCs and TMDs into the heterojunction devices via physical vapor deposition (PVD) of OSCs onto the TMD surfaces is challenging, since the low diffusion and ordering

of the organic molecules limits functional properties of the formed OSC films12,13. Here we report a methodology for fabrication of highly crystalline ultrathin (down to 15 nm) OSC

nanosheets with lateral dimensions up to 3-inch and their transfer onto arbitrary substrates. We employ this methodology for the assembly of van der Waals (vdW) heterostructures with

two-dimensional (2D) materials. As an example for 2D materials, we chose ML TMDs. In brief, water-soluble polyacrylic acid (PAA) thin films on silicon wafers were used as growth substrates

to form highly crystalline OSC films of pentacene or dinaphtho[2,3-b:2’,3’-f]thieno[3,2-b]thiophene (DNTT) via PVD. We show that these films can be controllably released as mechanically

stable nanosheets from the growth substrate by the dissolution of the water-soluble PAA substrate and transferred onto arbitrary substrates. We apply various characterization techniques such

as atomic force microscopy (AFM), X-ray diffraction and confocal microscopy to demonstrate the high crystallinity and therewith optical anisotropy of the OSC nanosheets before and after

transfer. We use the OSC nanosheets to fabricate field-effect transistors (FETs) and to study their performance. To this end, the nanosheets were transferred onto prefabricated electrodes to

realize wafer-scale bottom-contact FET arrays and their properties were compared with OSC films directly grown on the wafer by PVD. Besides that, the p-type OSC nanosheets were transferred

onto prefabricated n-type MoS2 device structures to realize high-performance ambipolar and antiambipolar FETs. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION RELEASE AND TRANSFER OF ORGANIC NANOSHEETS First, we

describe the transfer method. We spin coat a water-soluble PAA thin film on an oxygen plasma-treated 3-inch Si wafer. The PAA layer acts as the growth substrate for PVD of highly ordered

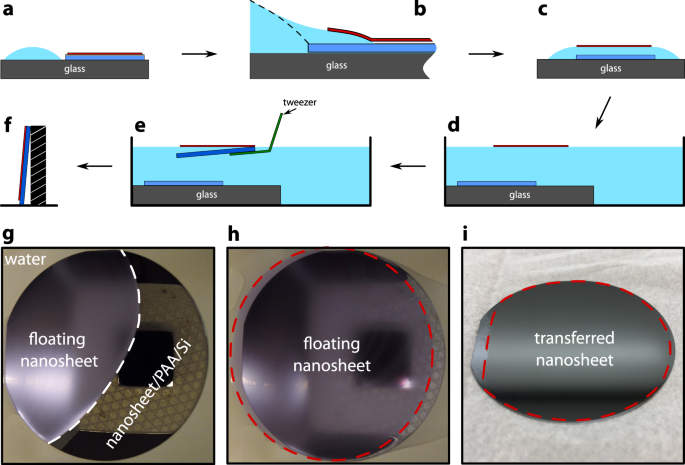

pentacene or DNTT films with thicknesses ranging from 15 to 50 nm. We found out that a controlled release of the OSC films is possible by a water-assisted transfer technique, see Fig. 1. We

place a Si wafer with the OSC film next to the water droplet, see Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1, and establish a contact between the wafer and the droplet, see Fig. 1b. The surface

tension difference between the untreated glass plate and the plasma-treated Si wafer drives the water towards the Si14; the water intrudes between the substrate and the OSC film, which

results in its release from the substrate and formation of a free-standing OSC nanosheet. Due to the hydrophobic nature of the OSC15, the released nanosheet floats on the water meniscus.

Although the rest of the OSC film is still sticking to the Si wafer at one side, it remains intact without rupture or cracking. A photograph of an intermediate state of the release of a 50

nm thick pentacene film from a 3-inch Si wafer is shown in Fig. 1g. Finally, by adding more water, the PAA dissolves completely and the whole mechanically stable OSC nanosheet floats on the

water surface, Fig. 1c. A photograph of such a 50 nm thick pentacene nanosheet is shown in Fig. 1h. After the organic film is released from the PAA template, the transfer of the OSC onto the

target substrate resembles other meniscus-based transfer schemes for all-organic heterojunctions, which instead require soluble molecules16,17,18. Further details on the PAA dissolution and

a time-lapse video of the process are provided in Supplementary Notes1 and in Supplementary Video 1. Next, the glass support with the floating OSC nanosheet on the wafer is immersed into a

water bath (Fig. 1d) and the floating OSC nanosheet is taken by the target substrate, Fig. 1e. Note that transfer of the nanosheet is particularly favorable on hydrophilic target substrates.

However, the transfer onto hydrophobic target substrates such as Si wafers after cleanroom processing is also possible. To this end, the edge of the target Si wafer needs to establish a

physical contact with the floating OSC nanosheet to enable vdW adhesion as shown schematically in Fig. 1e. Once the adhesion is established, the target wafer with the OSC nanosheet is taken

out of the water and dried in air. We found out that positioning the wafer almost vertically allows excess water to drain out easily and dry faster, Fig. 1f. A 50 nm pentacene nanosheet

transferred in this way on a 2-inch wafer is shown in Fig. 1i. STRUCTURAL AND OPTICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF TRANSFERRED ORGANIC NANOSHEETS Morphology and crystallinity of the OSC nanosheets

were characterized before and after transfer by AFM and X-ray diffraction. For 50 nm pentacene and DNTT nanosheets, PAA promotes the formation of large crystalline grains with lateral grain

size dimensions of ~6 µm and ~3 µm, respectively (see Fig. 2a, d). These grains are much larger than those obtained by the direct growth on oxide surfaces such as SiO2 and Al2O3, or on TMDs,

see Supplementary Fig. 3 for a comparison. After transfer, the grain morphology of the OSC nanosheets is preserved as verified by AFM, see Fig. 2b, e and Supplementary Fig. 4. X-ray

diffraction further confirms that PAA promotes OSC nanosheet growth in a single crystallographic phase, i.e., before transfer, there is only one series of Bragg peaks for both materials (see

black curves in Fig. 2c, f). The Bragg reflections of pentacene change after transfer (see red curve in Fig. 2c). Pentacene is known to exhibit different polymorphs such as thin film and

Campbell bulk phase which can be converted in response to stress19. Apparently, the transfer induces a stress sufficient to convert some fraction of the thin-film phase into Campbell bulk

phase20. Such stress might originate from the curvature of the water meniscus during the release of the OSC nanosheet. Stress-induced phase transitions have not been reported for DNTT. In

agreement, the crystallographic phase of the DNTT nanosheet is preserved after transfer. It is well-known that the optical reflection of pentacene grains is strongly polarization dependent

for some specific wavelengths, a phenomenon called Davydov splitting21. In order to probe for Davydov splitting, we raster scan the transferred pentacene nanosheet in confocal geometry with

a linear polarized laser beam (635 nm) (see Supplementary Notes4). Indeed, we found out that the reflection of individual grains depends on the polarization direction of the laser, which is

indicated by the yellow arrow in Fig. 2g, h. Each grain reflects only one of the two polarization states efficiently, as verified by a false-colour superposition map in Fig. 2i. This

observation confirms that the transferred pentacene nanosheets preserves their specific optical properties. TRANSPORT CHARACTERISTICS OF TRANSFERRED ORGANIC NANOSHEETS Next, the electronic

transport properties of transferred OSC nanosheets were investigated in the inverted coplanar field-effect geometry, i.e., bottom-contact and bottom-gate FETs, as shown in Fig. 3a (see also

Supplementary Fig. 5). A highly doped Si substrate is used as a global bottom-gate electrode and an ALD grown 33 nm alumina (Al2O3) film serves as the gate dielectric. A self-assembled

monolayer (SAM) of n-tetradecylphosphonic acid was used to passivate the alumina film6. Bottom-contacts were defined by shadow masks, which we use to evaporate a structured Ti adhesion layer

and Au contacts. Finally, a 50 nm DNTT nanosheet is transferred on the wafer. The device characterization is shown in Fig. 3b. The DNTT device exhibits an on/off ratio of up to 105 at _V_D

= −5.0 V, a threshold voltage of −0.63 V, and a little hysteresis of 217 mV (see Supplementary Fig. 6 for further transistor characteristics). The extracted mobility for DNTT is 0.16 cm2

V−1s−1 and the subthreshold swing is 289 mV per decade. A further improvement of the extracted OSC mobility might be possible by bottom-contact modification22. These values show that the

OSC/gate dielectric junction is structurally and energetically well-ordered after the nanosheet transfer, i.e. we see only mild signatures of the charge traps that typically lower device

performance in OSC bottom-contact devices. In addition, transferred nanosheet FETs with top-contacts show similar transfer characteristics as bottom-contact devices suggesting that the

well-known Au bottom-contact problems were resolved by transfer (Supplementary Fig. 7). Next, we compare the device with a transferred nanosheet with a similar device fabricated via direct

PVD of the DNTT. This device yields drain currents, which are more than one order of magnitude lower in comparison to the nanosheet device. The difference in performance can be further

quantified by square root plots of the drain current; here the devices should exhibit an extended linear characteristic curve according to Shockley theory23. Indeed, the transferred device

shows a linear region allowing for the extraction of the mobility, while the PVD device shows pronounced nonideal super-linear behavior, i.e., increasing slope with increasing gate voltage,

which prevents the mobility extraction24. Eye inspection of Fig. 3b reveals that the extrapolation of the threshold voltage (blue dashed line) is only valid for the four highest data points,

which is an indication of super-linear behavior24. For the transferred device, the extrapolation is valid for a much larger voltage region, shown as the blue line in Fig. 3b as well, an

indication of close to ideal behavior24. A well-known cause for pronounced nonideal behavior in bottom-contact devices is the structural disorder of the OSC/Au junction due to the inferior

growth behavior of organic molecules on Au surfaces25. Our results show that such growth problems are prevented in the FET devices made of the transferred OSC nanosheets. TRANSPORT

CHARACTERISTICS OF VAN DER WAALS HETEROSTRUCTURES Now, we demonstrate the vdW heterostructure devices made of OSC nanosheets and ML MoS2. We assemble vdW p-n heterojunction by transfer of

the OSC nanosheets onto ML MoS2 nanosheets. We tested two different device configurations resulting in ambipolar and antiambipolar FETs, see Fig. 4a, c. To this end, high-quality ML MoS2

single crystals26 were synthesized on thermally oxidized Si wafers by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) (see Supplementary Notes6). The MoS2 crystals were transferred by a PMMA assisted

transfer process27 and Au/Ti source/drain electrodes were patterned. Next, a 50 nm DNTT nanosheet was transferred (see Supplementary Fig. 9a). Figure 4b shows the transfer curves of such a

device under ambient conditions demonstrating the characteristic drain current V-shape of ambipolar FETs, see also Supplementary Figure 10. The current in the ambipolar region can be

expressed as the sum of an electron and hole current28: $$\left| {I_D} \right| = \frac{{WC_i}}{{2L}}\left\{ {\mu _e\left( {V_G - V_{Th,e}} \right)^2 + \mu _h\left( {V_D - (V_G - V_{Th,h})}

\right)^2} \right\}$$ (1) The drain voltage _V_D affects the threshold voltage of one of the two currents, (cf. Eq. 1), here the hole current, and in turn the transfer curve shifts in

response to the drain voltage, cf. Fig. 4b. Furthermore, the two asymptotic branches of the drain current allow us to model the saturation behavior of the ambipolar device to determine

electron and hole mobilities _µ_e, _µ_h and threshold voltages _V_th,e, _V_th,h. The DNTT/MoS2 vdW heterojunction device shows rather balanced mobilities of µh = 0.18 cm2V−1s−1 and µe = 0.25

cm2 V−1s−1. So far, similar balanced mobilities have only been reported for organic single crystals placed on 2D materials10. Such balanced mobilities are important in applications where

the device operates in bipolar or ambipolar mode, as needed for, e.g., inverters and oscillators29. We performed drain bias dependent ambipolar FET measurements to resolve the nature of the

conducting channel. We find that both channels (p and n) can be switched off in the ambipolar FET geometry via the gate, a typical behavior for a semiconductor (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b).

The drain current dip in the transfer curve provides additional information about the subthreshold behavior of the device. According to Eq. 1, the ambipolar current drops to zero for drain

voltages smaller than the electron and hole threshold voltage difference. Here, we measure a finite current of _I_D = 100 pA for _V_D = ±5.0 V in the minimum. This current can be explained

by subthreshold behavior of ML MoS2 and DNTT; i.e., we can model current in the minimum with a ML MoS2 subthreshold swing of 2.31 V per decade, see Supplementary Notes7 for further analysis.

The subthreshold swing allows to estimate the density of ML MoS2 subthreshold traps to _N_t,sub = 9.16 × 1012 eV−1cm−2 assuming a capacitance per area of _C_i = 38.4 nF per cm2. Similar

values are found for DNTT. The geometric design of the ambipolar device allows that current flows in the two junction materials without crossing the two materials. In order to enforce

current flow across the heterojunction, we employ now the antiambipolar geometry, Fig. 4c. In this geometry, the electrodes are exclusively in contact with one material only. Here, the

source is connected to a ML MoS2 and drain to a 50 nm pentacene nanosheet. The overlap region of the two materials, i.e., the p-n junction, is 15 µm along the channel length. Technically,

this configuration was realized with help of an insulating SU-8 polymer coating on one contact, and suited placement of the second contact (see Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 9b, 11). In

this antiambipolar geometry, the drain current minimum of the ambipolar geometry changes to a drain current maximum. This peak in drain current is the fingerprint of the antiambipolar

geometry, confirming that indeed a functional p-n heterostructure junction formed between a 2D material and a transferred OSC. The signal to noise ratio of the drain current maximum is up to

103, cf. Fig. 4d, exceeding previously reported values for this materials combination12. In summary, we have developed a method for wafer-scale (3-inch) synthesis and transfer of organic

semiconducting nanosheets with thickness down to 15 nm, demonstrated for the example of DNTT and pentacene. The nanosheets can be transferred onto arbitrary substrates by a water-assisted

transfer protocol. Unipolar devices fabricated via OSC transfer outperform prepared conventionally by PVD DNTT bottom-contact FETs by more than one order of magnitude in drain current.

Fabrication of ambipolar and antiambipolar devices with OSC and ML MoS2 was demonstrated and such devices reach the performance of heterojunction devices previously build from organic single

crystals, outperforming also OSC films deposited by PVD directly on MoS2. Such vdW heterojunction devices have potential application in optoelectronics as ultrafast photodetectors or

light-emitting devices. Further progress in this direction relies on the improvement of the subthreshold behavior. The OSC transfer method can be used to transfer OSC nanosheets to flexible

or curved substrates for applications in large area photodetection (see Supplementary Fig. 14), biomedical sensing applications30, and mechanical sensing as in artificial skin devices31.

METHODS ORGANIC SEMICONDUCTOR DEPOSITION Si wafer with SiO2 oxide surface were sonicated 5 min + 10 min in acetone and in isopropanol then 10 min DI at 60 °C. The SiO2 surface was activated

by an O2 (10 sccm) plasma treatment at 50 W for 5 min. An approx. 50 nm thick layer of PAA (volume fraction 2.5%, filtered by 0.22 µm pore-sized syringe filter) was spin-coated (60 s at 4000

rpm) onto the Si wafer. The wafers were immediately loaded into an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber and up to 50 nm thick pentacene or DNTT films were evaporated at a base pressure of middle

10−8 mbar. The OSC films were evaporated with a rate of 0.1 Å per s at room temperature for pentacene and with a rate of 0.1 Å per s at 60 °C for DNTT. AFM AND X-RAY MEASUREMENTS AFM images

are recorded by a Bruker Dimensional Icon. The deposition rates and substrate temperatures for the nanosheets used in AFM measurements are 0.02 Å per s at room temperature and 0.1 Å per s

at 60 °C for pentacene and DNTT respectively. For X-ray measurements an in house X-ray setup was used with Mo source and a monochromatic beam in reflection geometry. The deposition rates and

substrate temperatures for the nanosheets used in X-ray measurements are 0.1 Å per s at room temperature for both pentacene and DNTT films, respectively. DEVICE FABRICATION The shadow

polyimide mask for patterning organic FETs was manufactured by CADiLAC Laser GmbH. For vdW heterostructure FETs, SiO2 is used as gate dielectric and its thickness is 90 nm for ambipolar

DNTT/ML MoS2 FET and 300 nm for antiambipolar pentacene/ML MoS2 FET. The ambipolar FET was patterned by photolithography while the antiambipolar FET was patterned by e-beam lithography. OSC

nanosheets for FETs were evaporated with 0.1 Å per s at room temperature for pentacene and 60 °C for DNTT films. ELECTRICAL CHARACTERIZATION A probe station in dark ambient conditions was

used for organic FETs and DNTT/ML MoS2 ambipolar FET where pentacene/ML MoS2 antiambipolar FET was measured under vacuum. DATA AVAILABILITY The data that support the findings of this study

are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * Jariwala, D., Marks, T. J. & Hersam, M. C. Mixed-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures. _Nat.

Mater._ 16, 170–181 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gobbi, M., Orgiu, E. & Samorì, P. When 2D materials meet molecules: opportunities and challenges of hybrid organic/inorganic

van der Waals heterostructures. _Adv. Mater._ 30, 1706103 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Sun, J. et al. 2D–Organic hybrid heterostructures for optoelectronic applications. _Adv. Mater._

31, 1803831 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Horowitz, G. Organic field‐effect transistors. _Adv. Mater._ 10, 365–377 (1998). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yamamoto, T. & Takimiya,

K. Facile synthesis of highly π-extendedheteroarenes, dinaphtho [2, 3-b: 2’, 3’-f] chalcogenopheno [3, 2-b] chalcogenophenes, and theirapplication to field-effect transistors. _J. Am. Chem.

Soc._ 129, 2224–2225 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Klauk, H., Zschieschang, U., Pflaum, J. & Halik, M. Ultralow-power organic complementary circuits. _Nature_ 445, 745–748

(2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Leung, L. M. et al. A high-efficiency blue emitter for small molecule-based organic light-emitting diode. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 122, 5640–5641 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Radisavljevic, B. et al. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 6, 147–150 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Larentis, S., Fallahazad, B.

& Tutuc, E. Field-effect transistors and intrinsic mobility in ultra-thin MoSe2 layers. _Appl. Phys. Lett._ 101, 223104 (2012). Article Google Scholar * He, X. et al. MoS2/Rubrene van

der Waals heterostructure: toward ambipolar field‐effect transistors and inverter circuits. _Small_ 13, 1602558 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Wang, Z., Huang, L. & Chi, L. Organic

semiconductor field-effect transistors based on organic-2D heterostructures. _Front. Mat._ 7, 295 (2020). * Jariwala, D. et al. Hybrid, gate-tunable, van der Waals p–n heterojunctions from

pentacene and MoS2. _Nano Lett._ 16, 497–503 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kim, J.-K. et al. Trap-mediated electronic transport properties of gate-tunable pentacene/MoS2 p-n

heterojunction diodes. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 36775 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Eid, K., Panth, M. & Sommers, A. The physics of water droplets on surfaces: exploring the effects of

roughness and surface chemistry. _Eur. J. Phys._ 39, 025804 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Di, C.-a. et al. Effect of dielectric layers on device stability of pentacene-based

field-effect transistors. _Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys._ 11, 7268–7273 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, H. et al. Organic Heterojunctions Formed by Interfacing Two Single Crystals from

a Mixed Solution. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 141, 10007–10015 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Shi, Y. et al. Bottom-up growth of n-type monolayer molecular crystals on polymeric substrate

for optoelectronic device applications. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 1–8 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Xiao, M. et al. Sub-5 nm single crystalline organic p–n heterojunctions. _Nat. Commun._ 12,

1–7 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Murakami, Y. et al. Microstructural study of the polymorphic transformation in pentacene thin films. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 103, 146102 (2009). Article

Google Scholar * Westermeier, C. et al. Sub-micron phase coexistence in small-molecule organic thin films revealed by infrared nano-imaging. _Nat. Commun._ 5, 1–6 (2014). Article Google

Scholar * Cocchi, C., Breuer, T., Witte, G. & Draxl, C. Polarized absorbance and Davydov splitting in bulk and thin-film pentacene polymorphs. _Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys._ 20, 29724–29736

(2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Borchert, J. W. et al. Small contact resistance and high-frequency operation of flexible low-voltage inverted coplanar organic transistors. _Nat.

Commun._ 10, 1–11 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sze, S. M., Li, Y. & Ng, K. K. _Physics of Semiconductor Devices_ (John Wiley & Sons, 2021). * Choi, H. H. et al. Critical

assessment of charge mobility extraction in FETs. _Nat. Mater._ 17, 2–7 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bock, C. et al. Improved morphology and charge carrier injection in pentacene

field-effect transistors with thiol-treated electrodes. _J. Appl. Phys._ 100, 114517 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Shree, S. et al. High optical quality of MoS2 monolayers grown by

chemical vapor deposition. _2D Mater._ 7, 015011 (2019). Article Google Scholar * George, A. et al. Controlled growth of transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers using Knudsen-type

effusion cells for the precursors. _J. Phys. Mater._ 2, 016001 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zaumseil, J. & Sirringhaus, H. Electron and ambipolar transport in organic

field-effect transistors. _Chem. Rev._ 107, 1296–1323 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zschieschang, U. et al. Roadmap to gigahertz organic transistors. _Adv. Funct. Mater._ 30,

1903812 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Werkmeister, F. & Nickel, B. Towards flexible organic thin film transistors (OTFTs) for biosensing. _J. Mater. Chem. B_ 1, 3830–3835

(2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ramuz, M., Tee, B. C. K., Tok, J. B. H. & Bao, Z. Transparent, optical, pressure‐sensitive artificial skin for large‐area stretchable electronics.

_Adv. Mater._ 24, 3223–3227 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS B.N. and S.B.K. acknowledge Philipp Altpeter (LMU) for cleanroom support, Domenikos

Chryssikos (TUM) for the SAM modification recipe, Joachim Rädler (LMU) for comments on wetting physics and Michel de Jong (UT) for ALD grown alumina wafer. All authors acknowledge financial

support by EU within FLAG-ERA JTC 2017 managed Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) under contract nr. NI 632/6-1 and TU 149/9-1. B.N. acknowledges support from the Bavarian State Ministry

of Science, Research and Arts through the grant “Solar Technologies go Hybrid (SolTech)”. FUNDING Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes *

These authors contributed equally: Sirri Batuhan Kalkan, Emad Najafidehaghani. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Faculty of Physics and CeNS, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität,

Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539, Munich, Germany Sirri Batuhan Kalkan, Fabian Alexander Christian Apfelbeck & Bert Nickel * Institute of Physical Chemistry and Abbe Center of

Photonics, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Lessingstr. 10, 07743, Jena, Germany Emad Najafidehaghani, Ziyang Gan, Antony George & Andrey Turchanin * Leibniz Institute of Photonic

Technology (IPHT), Albert-Einstein-Str. 9, 07745, Jena, Germany Uwe Hübner Authors * Sirri Batuhan Kalkan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* Emad Najafidehaghani View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ziyang Gan View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Fabian Alexander Christian Apfelbeck View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Uwe Hübner View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Antony George View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrey Turchanin View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bert Nickel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS The

research project was initiated by B.N. and A.T. S.B.K., A.G., A.T., and B.N. developed the OSC transfer technique. S.B.K. pursued the growth and transfer of organic nanosheets including

their characterization with help from F.A. E.N., Z.G. and A.G. carried out the preparation of TMDs. S.B.K. and U.H. fabricated OSC/TMD devices. S.B.K. characterized the unipolar and

ambipolar FETs while E.N. and A.G. measured the antiambipolar FET. S.B.K. and B.N. analyzed the FET characteristics and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final form of the

manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Andrey Turchanin or Bert Nickel. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS An institutional patent application titled “Method of transfer

of organic semiconductor films to a substrate and electronic devices made therefrom” with the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (GPTO) was filed by FSU Jena with the official file number

“10 2021 107 057.0.” Inventors (share equal part, in alphabetic order): Antony George, Sirri Batuhan Kalkan, Bert Nickel, Andrey Turchanin. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer

Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO 1 RIGHTS

AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in

any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The

images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Kalkan, S.B.,

Najafidehaghani, E., Gan, Z. _et al._ Wafer scale synthesis of organic semiconductor nanosheets for van der Waals heterojunction devices. _npj 2D Mater Appl_ 5, 92 (2021).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-021-00270-9 Download citation * Received: 14 July 2021 * Accepted: 29 October 2021 * Published: 03 December 2021 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-021-00270-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative