Both left and right: thatcher’s undeniable influence on australian politics

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

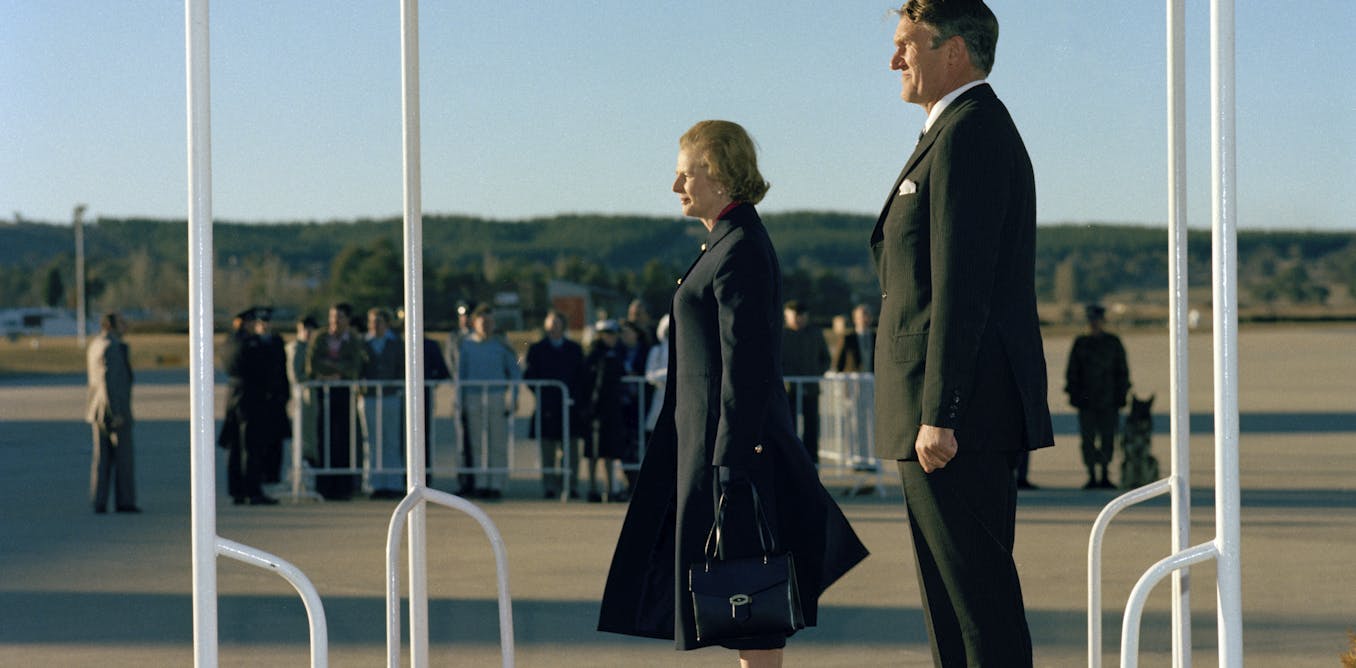

Margaret Thatcher’s years as British prime minister from 1979 to 1990 coincided with an era of political upheaval in Australia. The exhaustion of Malcolm Fraser’s “Menziesian” liberalism was

followed by the successful and pragmatic Labor governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating. Both sides of Australian politics were influenced by the example of Thatcher, but her influence was

most significant on the Labor party and the broader left. To the struggling Liberal party, Thatcher’s government provided a beacon of hope, just as Tony Blair did for Labor in the 2000s.

Australia even in the 1980s was a much more British society than now. British migrants were well-represented among Liberal activists, and many had left Britain at least partially in response

to union power and non-white immigration - issues that contributed to Thatcher’s support. To many Australian conservatives, Thatcher seemed to provide an example of commitment politics: one

that compared favourably to the temporising of the Fraser years. There were however difficulties in the application of Thatcher’s formula to Australia. The contemporary image of Thatcher

largely rests on her economic record, but much of her early support base rested on nationalism and social conservatism. In 1978 she empathised with white Britons who feared being “swamped”

by migrants of a “different culture”. In Australia, Thatcher’s aggressive social conservatism - she spoke of the “loony left” and legislated to prevent local authorities from the “promotion”

of homosexuality - was counterproductive for the Liberal party. John Howard’s comments about Asian immigration in 1988 were, as he later admitted, politically costly. Nor could the Liberals

in opposition compete with Bob Hawke’s tendency towards nationalism. The Liberals were also often seduced by the spirit of Thatcher’s rhetorical radicalism rather than its more cautious

substance. In 1983, Thatcher boasted that Britain’s National Health Service was “safe with us”. The Australian Liberals, however, tied themselves in knots over their opposition to Medicare.

Thatcher’s successes with privatisation excited the Australian right, but voters were unenthused. There was no Australian equivalent of council housing sales to provide a bonanza to voters.

The Liberals also misread Thatcher’s successes on industrial relations. Australian unions were unpopular - although not as much as in Britain - but Labor under Bob Hawke appealed to voters

as best equipped to manage them. The fact that Australian workplace regulation relied in large part on the eternally popular arbitration system, rather than union power as in Britain,

weakened the case for labour market deregulation further. In large part, then, Thatcher’s legacy was a costly one for the Australian right. The lessons of combat from government against a

militant union movement and a radical Labour Party in the UK did not easily translate to Australia with its pacific unions and centrist Labor government. In fact, Margaret Thatcher’s most

direct impact on Australian politics was on the left. In these years the Australian labour movement was deeply informed by British debates. To many on the left, the Thatcher model

represented the likely fate of Australia if the Hawke government was defeated. This fear guided those informed by the traditions of British unionism, such as a young Doug Cameron (now an ALP

senator), but also much on the intellectual left which included many British migrants. Fear of an Australian version of “Thatcherism” made many on the left less critical of the Hawke

government and enabled Labor to pursue a centrist course. The experience of Thatcher also guided much of the left’s positive response. For many of the British left, Thatcher’s government was

more than just a revived conservatism. Rather, she was the advocate of Thatcherism: a sustained project to remake British society. It reflected a deep-seated, “organic” crisis of the

“Keynesian welfare state” that had emerged after World War II. A decade later John Howard earned a similar fascination from much of the left in Australia. In Britain, this interpretation of

Thatcherism was pioneered by the Communist party’s journal Marxism Today, in particular contributors such as Stuart Hall, and was echoed by its local equivalent the Australian Left Review.

To Hall and his co-thinkers, Thatcherism’s popularity originated in errors in the practice of the left. Socialists, Hall and his colleagues argued, did not recognise the disillusionment of

many working class people with the bureaucratic state, while British unions although industrially strong had not offered any alternative hegemonic vision. In Australia, working class

distrust of the state meant a preference for tax cuts over more government services. The Hawke government’s Accord with unions emphasised the maintenance of take-home pay over an enlarged

public sector to the frustration of the traditional (and feminist) left. The failure of British unions to defeat Thatcher seemed to demonstrate that the Australian way of cooperation with a

Labor government was preferable. In the end, however, Australian unions found themselves locked in behind a Labor government whose economic orthodoxy was praised by Thatcher herself. By the

early 1990s aspects of Thatcher’s legacy seemed attractive to Australian Labor politicians, in particular privatisation and the acceptance of deindustrialisation. Yet some aspects of the

left’s critique of Thatcherism would continue to inform the practice of Hawke and Keating’s Labor government. Hall argued for the left to fight the cultural battle against Thatcherism by an

engagement with new social movements such as those for multiculturalism, environmentalism and gay rights. Within limits, Australian Labor between 1983 and 1996 did take up the cause of these

social movements. The Gillard Labor government has instead tended to acquiesce in Howard’s social conservatism around issues such as marriage equality and immigration. Thatcherism was one

element in the transformation of Australian society and economy during the 1980s. Thatcher’s local influence reflected not only the persistence of British-Australia into the 1980s on both

the left and right sides of politics, but also the shared crisis of the Keynesian welfare state in both countries.