In-vivo efficacy of chloroquine to clear asymptomatic infections in mozambican adults: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with implications for elimination strategies

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Recent reports regarding the re-emergence of parasite sensitivity to chloroquine call for a new consideration of this drug as an interesting complementary tool in malaria

elimination efforts, given its good safety profile and long half-life. A randomized (2:1), single-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in Manhiça, Mozambique, to assess the

_in-vivo_ efficacy of chloroquine to clear plasmodium falciparum (_Pf_) asymptomatic infections. Primary study endpoint was the rate of adequate and parasitological response (ACPR) to

therapy on day 28 (PCR-corrected). Day 0 isolates were analyzed to assess the presence of the _PfCRT_-76T CQ resistance marker. A total of 52 and 27 male adults were included in the CQ and

Placebo group respectively. PCR-corrected ACPR was significantly higher in the CQ arm 89.4% (95%CI 80–98%) compared to the placebo (p < 0.001). CQ cleared 49/50 infections within the

first 72 h while placebo cleared 12/26 (LRT p < 0.001). The _PfCRT_-76T mutation was present only in one out of 108 (0.9%) samples at baseline, well below the 84% prevalence found in 1999

in the same area. This study presents preliminary evidence of a return of chloroquine sensitivity in Mozambican _Pf_ isolates, and calls for its further evaluation in community-based

malaria elimination efforts, in combination with other effective anti-malarials. _Trial registration:_ www.clinicalTrials.gov NCT02698748. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS _PLASMODIUM

FALCIPARUM_ PHENOTYPIC AND GENOTYPIC RESISTANCE PROFILE DURING THE EMERGENCE OF PIPERAQUINE RESISTANCE IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND Article Open access 28 June 2021 ARTEMISININ COMBINATION

THERAPY FAILS EVEN IN THE ABSENCE OF _PLASMODIUM FALCIPARUM KELCH13_ GENE POLYMORPHISM IN CENTRAL INDIA Article Open access 11 May 2021 TRANSMISSIBILITY OF A NEW _PLASMODIUM FALCIPARUM_ 3D7

BANK FOR USE IN MALARIA VOLUNTEER INFECTION STUDIES EVALUATING TRANSMISSION BLOCKING INTERVENTIONS Article Open access 16 April 2025 INTRODUCTION In recent years, interest in the potential

use of Chloroquine (CQ) has re-emerged, partly on account of the observation that the prevalence of molecular markers associated with CQ resistance among circulating parasites has decreased

after discontinuing the use of the drug. The emergence of CQ resistance was first documented in Southeast Asia and South America less than a decade after its introduction as first-line

treatment and spread to the East of Africa and the rest of the continent by the end of the 1970’s1,2,3. In 2001 the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended artemisinin-based combination

therapy (ACT) as the first line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in countries where _Plasmodium falciparum_ (_Pf_) malaria had become resistant to CQ4, and since then the use of CQ for

the treatment of _Pf_ has progressively been abandoned. Drug-resistant microorganisms are generally thought to suffer from a fitness cost associated with their drug-resistant trait5,

inflicting them a disadvantage when the drug pressure reduces. Such finding implies that resistance might be reversible if drug use is discontinued. A point mutation in the 76th position of

the _P. falciparum_ CQ-resistance transporter gene (_PfCRT_) from a lysine in sensitive parasites (K76) to a threonine in resistant parasites (76 T) has been associated with CQ-resistant

_falciparum_ malaria6. Analysis of the population frequencies of the mutations in _PfCRT_ known to be associated with CQ resistance7 and assessment of _in vitro_ activity of the drug8, 9 in

Malawian parasite isolates have indicated that CQ resistance may revert to sensitivity within a decade of withdrawal of the drug10. Similar drops, have been shown in Zambia11, Tanzania12 or

coastal Kenya (Kilifi)13, years after CQ had been withdrawn. Translation of _in vitro_ sensitivity to _in vivo_ efficacy has also since then been demonstrated in Malawi14, where CQ efficacy

in patients has been confirmed as very high14, and its use as monotherapy in a clinical trial context -albeit not a WHO recommendation- has also been shown to be similarly efficacious to its

combination with other partner drugs15. In Mozambique, which borders in the west with Malawi, the national policy moved away from using CQ in 2003–4. A study conducted among children from

Manhiça District in 1999 revealed a _PfCRT 76_ _T_ prevalence of 84%16. However, a recent study performed in Gaza Province showed also an important decline of _PfCRT_ K76T prevalence from

more than 90% in 2006 to around 30% in 201017. A similar study conducted in a different part of the country also confirmed this tendency towards an increase of wild type parasites and thus

CQ sensitivity18. The last available efficacy results for CQ derived from an _in vivo_ study performed in Mozambique in the year 2001 showed that the day 28 efficacy was 47.1%19. Altogether,

these data suggest that, in the absence of drug pressure, CQ may be regaining sensitivity against _P. falciparum_ in certain malaria-endemic settings of Sub-Saharan Africa. While this does

not support the reintroduction of CQ as first line therapy in such settings at this point, it does suggest that, if proven sensitive in a given area, CQ could be considered as a

complementary tool to interrupt transmission in the context of malaria elimination efforts. With this rationale in mind, we conducted a randomized placebo-controlled single blinded clinical

trial to assess the efficacy of CQ (vs. placebo) to treat asymptomatic infections among healthy adult Mozambican volunteers. We complementarily present prevalence estimates of the _PfCRT_

K76T molecular marker of CQ resistance among parasites among the study population in 2015. METHODS The protocol for this trial and supporting CONSORT checklist, are available and annexed as

supporting information. STUDY DESIGN Between January and June 2015, a randomized, single-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in the district of Manhiça, southern Mozambique, to

treat asymptomatic infections among healthy adults from the community. This study population was considered as the most ethical option for the first _in-vivo_ study to take place since 2001,

when CQ had been shown to be poorly efficaciuos. A placebo comparator was consequently used to accurately account for the effect that the high levels of immunity expected in the study

population would have on natural parasite clearance of low parasitaemic infections20. STUDY SITE The district of Manhiça counts with a demographic surveillance system (DSS) set up in 1998 by

the _Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça_ (CISM), which currently provides accurate demographic information on its _circa_ 178,000 inhabitants. The region has two distinct seasons –

a warm and rainy season from November to April, and a cooler and drier season the rest of the year. Malaria transmission is perennial but shows marked seasonality, with _Plasmodium

falciparum (Pf)_ being the predominant species, and _Anopheles funestus_ the main vector. Study participants were selected from areas within Manhiça were clinical malaria in children was

historical known to be high (above 40%) and asymptomatic infections in adults were expected in the community21. SCREENING AND RECRUITMENT OF STUDY SUBJECTS The study population comprised

adult males with microscopically confirmed, asymptomatic malaria infections. In order to find these subjects, a random list was generated from the DSS databases, and individuals were visited

in their household, and screened for malaria through finger-prick with an HRP2-based rapid diagnostic test (RDT) and a blood slide. Blood slides were only read at CISM’s laboratory in those

cases found to be positive by the RDT (“pre-screened positive”), providing a final confirmation of malaria infection and density of parasitaemia. On the following day, such individuals were

again visited at home, and only if they remained symptomless were offered to be included in the study. Study staff enquired about the presence of symptoms by asking a series of questions

following a standardised clinical questionnaire. Asymptomatic malaria was defined as the absence of any proactively referred symptom of disease as referred by the individual, together with a

documented axillary temperature <37.5 °C. Symptomatic patients, irrespective of being infected or not, were assessed by the study clinician and referred to the health system if needed.

Females were not screened on account of the Mozambican Ethics Committee’s recommendation to avoid exposing to placebo malaria-infected women of child-bearing age which may be pregnant and

thus prone to developing severe disease. Other inclusion criteria included _Pf_ malaria infection with an asexual blood density ≥100 p/µL but <10,000 p/µL. Key exclusion criteria included

presence of any other co-existing clinical condition or symptom that in the opinion of the recruiting physician would not allow the individual to be considered a “healthy” asymptomatic

carrier; axillary temperature > = 37.5 °C; intake of any medication which may interfere with antimalarial efficacy or antimalarial pharmacokinetics, such as cotrimoxazole; history of

hypersensitivity reactions or contraindications to CQ; and known HIV concomitant infection under antiretroviral treatment. Individuals aged 18 years or more satisfying the inclusion criteria

were enrolled if they signed a detailed written informed consent. Individuals aged 16 were offered participation provided their legal guardians also assented for participation. TREATMENT

After the pre-screening visit (Day “−1”), a screening evaluation was conducted 24 hours later (day 0) to check all inclusion and exclusion criteria, with a particular emphasis on ensuring

that symptoms had not appeared. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive CQ (Arm 1) or Placebo (PL; arm 2), according to a 2:1 (CQ:PL) scheme, so as to have more patients in the

CQ arm to provide better estimates for its cure rates. Patients having received on day 0 a study drug, but confirmed by the blood slide to be malaria infection negative or <100

parasites/µL were considered protocol violations, and excluded from the analysis. A randomization list was generated using the online available randomizer software

(http://www.randomizer.org/). Study staff carried the study medication and directly supervised the three-day long treatment. Chloroquine sulphate (Meriquine®; 250 mg; 150 mg of chloroquine

base; Baroda, India) was administered at a total dose of 25 mg/kg (expressed as mg of CQ base per kg body weight, once daily during 3 consecutive days, following the schedule 10 mg/kg Day 1;

10 mg/kg day 2 and 5 mg/kg day 3; or four, four and two pills per day, respectively). A similarly-looking placebo not containing any active principle, and prepared at the department of

pharmacology of the Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain, was administered to those allocated this intervention following an identical scheme. All treatments were directly observed for a

minimum of 30 min. Any subject vomiting during this observation period was re-treated with the same dose of either CQ or placebo, and observed for an additional 30 min. Repeated vomiting

implied withdrawal from the study and the use of rescue treatment. Treatment of symptomatic malaria infections or rescue therapy in cases of early or late treatment failure followed national

Mozambican guidelines and included the use of artemether-lumefantrine (AL)22. EVALUATION Follow-up visits were planned on days 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 21 and 28 after enrolment, or at any time

point should the enrolled individual develop any symptoms of sickness. Individuals who discontinued either study drug were excluded from the study. Vital signs and body temperature were

assessed during each follow-up visit. Adverse events were recorded and assessed for severity and association with study medication. Thick and thin Giemsa-stained blood slides were prepared

prior to the administration of the drug and at every follow-up visit. Slides were examined by two independent microscopists and considered negative if no parasites were seen after

examination of 200 oil-immersion fields in a thick blood film. Parasite density was estimated using the Lambaréné method23 which counts parasites against an assumed known blood volume.

Density of _P. falciparum_ was assessed from blood-spots collected in filter paper through real-time quantitative polymerase chain-reaction (qPCR) assay targeting 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA)24,

25. Blood spots for PCR analysis were collected using 3M Whatman™ filter papers at baseline and at days 7, 14, 21 and 28, on the day of treatment failure or at any other unscheduled visit,

and subsequently stored at 4 °C in plastic zip bags containing silica gel dessicant. PCR was performed centrally (Barcelona, Spain) for all cases of recurrent parasitaemia from day 7

onwards, or for whom evidence of parasite clearance had been documented, and including DNA extraction using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). The three polymorphic genetic markers MSP1, MSP2,

and GluRP, were also investigated to distinguish recrudescence from new infections, according to WHO recommended procedures26. Recrudescence was defined as at least one identical allele for

each of the three markers in the pre-treatment and post-treatment samples. New infections were diagnosed when all alleles for at least one of the markers differed between the two samples.

CLINICAL TRIAL OUTCOMES Treatment outcomes were classified on the basis of an assessment of the parasitological and clinical response to antimalarial treatment according to the latest WHO

guidelines27. However, as all recruited subjects were asymptomatic at baseline, some of the standard clinical endpoints such as fever clearance time were not applicable. The primary efficacy

outcomes were the PCR-corrected early treatment failure (ETF), late clinical failure (LCF), late parasitological failure (LPF) and adequate clinical and parasitological response (ACPR) at

day 28. ACPR was defined as the absence of parasitemia at the end of the trial’s follow-up period (Day 28), regardless of axillary temperature, without having previously met any of the

criteria for early and late treatment failure. In the PCR-adjusted analyses, patients with recurrent infection were considered ACPR if this was classified as a new infection. Secondary

outcomes included 28 day-uncorrected ACPR (crude efficacy), time to parasite clearance, parasite clearance curve during the first 72 hours of follow-up, and prevalence of

chloroquine-resistance conferring _PfCRT_ K76T mutation in pre-treatment infections. ASSESSMENT OF PFCRT K76T MUTATIONS Purified DNA templates were amplified using 2720 Thermal Cycler

(Applied Biosystems) by nested PCR amplification followed by Sanger sequencing for _PfCRT_ gene. In brief, a first round of amplifications was performed in 25 μl reactions including 5 μl of

template DNA, 0.5 μM of each forward (_PfCRT__F-5′tttaggtggaggttcttgtctt-3′) and reverse (_PfCRT__R-5′ atacttaattgaagaacaaatgattgga-3′) primers and 1x HOT FirePol Master Mix (Solis BioDyne;

Cat. No. 04-27-00125). The template DNA was denatured at 95 °C for 15 min in a thermocycler, followed by 25 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 1 min, 52 °C for 45 sec, and 72 °C for 45 sec)

and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. A reaction using 5 μl of PCR-grade water instead of template DNA was included as a negative control. For the nested amplification, 5 μl of the PCR

product from the first amplification was used as the template in a PCR reaction (50 μl final volume) containing 0.5 μM of each forward (_PfCRT__F) and reverse

(_PfCRT__N_R-5′ttggtaggtggaatagattctct-3′) primers and 1x HOT FirePol Master Mix (Solis BioDyne). The reaction volume was make up by PCR-grade water. The template DNA was denatured at 95 °C

for 15 min in a thermocycler, followed by 35 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 30 sec, 50 °C for 45 sec, and 72 °C for 45 sec) and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were

run on 2% agarose (Invitrogen) gels in 1 × TBE buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to determine the presence and size of the amplified DNA. PCR products were visualized using a UV

trans-illuminator. Both PCR primer sets were also tested with human gDNA to check their specificity. Three positive (7G8, Dd2, and V1/S) controls with known _PfCRT__76 T allele were also

processed and amplified at the same time as the studied samples. Positive and negative controls were added in every run. The expected size of the nested PCR was 319bp covering amino acid

positions 35 to 120 from _PfCRT_ in the 3D7 strain. PCR products were quantified using EPOCH Biotech system. Approximately 1200ng of PCR products were sent to Genewiz, following safety

instructions for the accurate shipment of PCR amplicons. PCR sequencing was performed in both directions using specific forward and reverse primers of studied genes. The variations in the

test sequences were identified by sequence alignment against reference sequence of 3D7 (PF3D7_0709000) retrieved from PlasmoDB. DATA MANAGEMENT AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Data were recorded

using standardized questionnaires specifically designed for this study, which were doubled-entered into a study-specific database created using open clinica software (OpenClinica Enterprise

- Electronic Data Capture Software for Clinical Trials version 3.1.2, OpenClinica LLC, Waltham, MA, USA). Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX,

USA), and the statistical significance level was set at 5%. Safety outcomes were assessed in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which comprised all patients who received one or more doses

of study medication and underwent at least one post-baseline safety assessment. Efficacy was calculated in the according-to-protocol population (ATP), which included all patients fulfilling

the protocol eligibility criteria, who completed the three-day course of study medication, with no protocol violations, accomplishing the day-28 assessment and having an evaluable PCR in

case of recurrent parasitaemia. Kaplan-Meier estimates were computed to estimate the cumulative proportion of treatment success until day 28; and Log-Rank tests used to compare the number of

events in each arm. For such an analysis, losses to follow-up and study withdrawals were censored on the last day of follow-up. Cases with re-infections were also censored from the analysis

on the day of detection. Finally, linear regressions and Likelihood Ratio Tests (LRT) of the log-transformed parasite densities during the first 72 hours of treatment were estimated to

better characterize the parasite clearance curve during treatment between study groups. Frequencies of mutations at _PfCRT_-76 alleles were calculated as the proportion of samples carrying

the mutant form out of all samples processed. Samples carrying both wildtype and mutant forms, in which relative frequencies could not be determined, were excluded from the denominator and

numerator13. SAMPLE SIZE CALCULATIONS Following WHO guidelines28, and assuming an unknown failure rate, a minimum sample of 50 patients was considered necessary to provide a meaningful

evaluation of _in vivo_ efficacy, regardless of the underlying rates of failure. For the placebo group, the proportion of parasites that are eliminated naturally by the host’s immune system

after 28 days in Manhiça is unknown, but expected to be less than one percent29,30,31. Thus, the sample size for the control group needed not be the same size as the treatment group in order

to detect a significant difference in prevalence. If 25 controls were recruited (placebo arm), then, even if half of the controls were to clear their infections, we will still achieve a

p-value of less than 0.001 from a Chi-square test with one degree of freedom (Fisher’s exact test would also yield a p-value less than 0.001). Therefore, our objective was to recruit 75

participants total, i.e. 50 to receive CQ and 25 to receive PL. ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS This protocol, consent forms and questionnaires were approved by the CISM local ethics committee, the

Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona (HCB/2015/0122), the National Bioethics Committee of Mozambique (CNBS; Ref:173/CNBS/13) and the Mozambican pharmaceutical department

(Ref./N°4110/380/DF2014) before their implementation. The methodology used in this study was performed in accordance with the relevant regulations and guidelines from all committees. All

participants signed an Informed consent form prior to the initiation of any study related activities. All samples for the separate analysis of trends in CQ resistance were obtained under an

informed consent, and after individual ethical approvals for each of the parent studies by CNBS. The trial was registered on January the 13th, 2015, at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02698748).

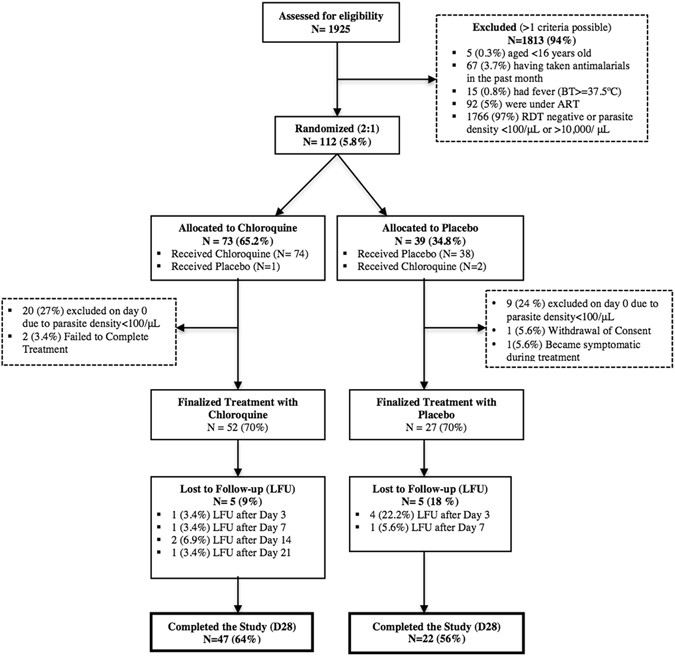

RESULTS TRIAL PROFILE AND BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS A total of 1925 adult males were approached and pre-screened (Day −1) for symptomatology and malaria infection. Of those, 112 (5.8%)

fulfilled _a priori_ inclusion criteria and were randomized (Day 0) to receive either CQ (n = 73; 65.2%) or PL (n = 39; 34.8%). Median age of randomized individuals was 21.5 years (IQR

17–35). No significant differences were observed between subjects randomized to receive either CQ or PL (Table 1). Main reasons for exclusion was the absence of malaria parasites at

pre-screening and/or the concomitant use of antiretroviral or antimalarial drugs. The ITT and ATP populations included 112 and 79 individuals, respectively. One patient that should have

received CQ was given by mistake PL, and conversely, two patients that should have received PL were treated with CQ, which resulted in 74 participants in the CQ arm and 38 in the PL. In

those three cases, subjects continued with the same treatment for the entire 3 days. Two patients in the CQ group did not complete the entire 3-day long treatment. A single patient in the PL

group had to be withdrawn from the study and given rescue treatment after developing clinical symptoms. 52 patients finalized the CQ treatment, and 27 finalized the PL. Of these, 47

subjects allocated to receive CQ (64%) and 22 to PL (56%) concluded with all available information the 28 day long follow-up (Fig. 1). SAFETY In terms of tolerability and safety of the

interventions, the symptoms reported during the three-day treatment course did not significantly vary between study arms (Table 1). No serious adverse events occurred, and all AEs were very

mild and deemed not related with the interventions except for a case of mild pruritus reported from one patient in the CQ group. EFFICACY The day-28 PCR-uncorrected cure rate (i.e., the

proportion of patients with ACPR, ATP population, without correcting by PCR) was 89.4% (42/47; 95% CI 80.5–98.2) for CQ, and 18.1% (4/22; 95% CI 2.1–34.3) for PL (p < 0.001).

PCR-correction did not change the D28 ACPR for CQ, which remained 89.4% (42/47; 95% CI 80.5–98.2) given that the only new infection identified in this group was lost to follow-up after day

21; but increased that of PL (28.6%; 4/14; 95% CI 4.9–52.2), as 8 of the treatment failures proved to be new infections, and were consequently excluded from the analysis (Table 2). Figure 2

illustrates the Kaplan Meier curves showing the treatment success cumulative proportion for each treatment until day 28, both for the PCR uncorrected (2a) and PCR-corrected (2b) in the ATP

population. PARASITE CLEARANCE WITHIN FIRST 72 HOURS Only one (2%) of the 50 participants in the CQ arm still presented an infection (24 p/μL) 72 hours after the administration of the first

dose. Conversely, 14 (54%) of the 26 individuals in the placebo group were infected at the same point in time, with parasite densities ranging from 22 to 28,089 p/μL. Finally, the linear

regressions fitted to the log-transformed parasite densities at 0, 24, 48 and 72 hours revealed significantly different rates of parasite clearance (LRT of interaction p-value = 0.02)

between study arms (Fig. 3). PFCRT 76 MUTATIONS AMONG ISOLATES FROM THE CLINICAL TRIAL Among 110 samples, 108 samples were used to assess the presence of _PfCRT_ K76T mutation by

bi-directional DNA sequencing. Further, these sequences were aligned, using NCBI-Blast online tool against the reference sequence of 3D7 (PF3D7_0709000) retrieved from PlasmoDB. Three

positive control data were in accordance with existing data. Only one of the 108 (0.9%) samples analyzed was found to have the mutant allele (Fig. 4). Four additional samples (3.7%) had

mixed infection, and wild type allele frequency was 95.4% (103/108). DISCUSSION In the continuum of strategies governing the transition towards malaria elimination32, there has been renewed

interest in the innovative reappraisal of CQ as an antimalarial to be used in community-based campaigns. However, evidence is needed to demonstrate that CQ-based regimens will be effective

over a wide geographic area where malaria elimination interventions will be implemented. This study presents a return of chloroquine sensitivity in Mozambique approximately 12 years after

its use was interrupted. In the last decade, the presence of resistant parasites has dropped from 84% in 199916 to 0.9% in 2015. Additionally, in 2015 chloroquine successfully cleared 89% of

asymptomatic infections among a population of male adults from an endemic area, when compared to infections treated with placebo. The rate of parasite clearance was also significantly

faster among chloroquine-treated infections compared to those left untreated and, as expected, there were no adverse events associated to the medications. This study provides the first

evidence to support the idea that CQ could play a role, on its own or in combination with other drugs or tools, in the fight against malaria in Mozambique. The drug efficacy observed in the

present clinical trial is promising despite falling below the WHO recommended 95% efficacy rate for antimalarial drugs28. The methodology used to assess efficacy in this study was unusual

for an anti-malaria efficacy study, thus conditioning the interpretation of its results to the advantages and disadvantages of the clinical trial procedures followed. Comparing chloroquine

versus placebo allowed to test the hypothesis that chloroquine was as inefficacious as not providing any treatment at all. By having an untreated control, this methodology allowed assessing

whether the cleared infections observed in the chloroquine group were solely due to the body’s natural capacity to eliminate the parasite reservoir rather than due to the effect of the drug.

The placebo group of this study revealed that approximately 18% of the low-parasitemia infections are naturally cleared 28 days after they have been identified, a larger proportion compared

to what has previously been reported23,24,25. In addition, only one individual developed clinical symptoms among all untreated asymptomatic participants. This is therefore an unprecedented

opportunity for further exploration of the relatively unknown symptom-less malaria infection33, which will be performed in detail and presented in a separate article. Considering the low _in

vivo_ efficacy of chloroquine detected in the same study area prior to this clinical trial19, the study only included asymptomatic infections to avoid treatment failures that could trigger

complications to the study participants. This study population implies several limitations inherent to the nature of asymptomatic infections. First, the high levels of existing immunity in

the study population may have augmented the efficacy of the drug, although this was controlled for in the analysis by observing the natural parasite clearance rate in the placebo group with

the same levels of immunity20. Unfortunately, the study design did not consider regular estimations of parasite densities during the first days of follow-up, which limited our capacity to

accurately estimate parasite reduction rates (PRR) in both treatment groups as a surrogate of drug efficacy34. Second, low parasitaemic infections (approximately 500 p/μL) could have

potentiated drug efficacy, which needs to be assessed further in future studies involving clinical malaria cases with higher loads of parasite biomass. The evaluation of drug efficacy in low

parasite density infections carried additional challenges, particularly when performing molecular analysis to comply with WHO standard analysis procedures35. Due to low parasitaemia, the

sensitivity of the genotyping techniques was low, and therefore PCR-Corrected analysis was considered biased. As a result, PCR-uncorrected analysis should be considered as a more precise way

of analyzing the efficacy of chloroquine in this particular study population. The standard PCR-Corrected analysis was also limited by the very nature of the control group, which consisted

of natural, untreated, asymptomatic infections. Participants in the placebo group were consequently vulnerable to reinfections and parasite density oscillations around the microscopy

detection threshold that could be interpreted as recrudescences or reinfections rather than as a chronic low parasitemic infection4. Despite all of the above, the high _in vivo_ efficacy

found in Southern Mozambique through this clinical trial aligns well with the findings obtained molecularly that detected a sharp decline in the prevalence of drug-resistant parasites

between 1999 (84%) and 2015 (0.9%) in the same area. Such a shift in the parasite population after the interruption of CQ use has been observed in several countries in Africa10, 12, 13, 36.

This reversal to the wild type form of the _PfCRT_ gene indicates that parasites carrying the mutant _PfCRT_ may have a substantial fitness cost in the absence of CQ, thus leading to their

decline in frequency once drug pressure is removed14. In some instances, loss of fitness may be associated with the development of compensatory mechanisms, leading to persistence of the

mutant parasite in the population despite the discontinuation of the drug. This feature may explain, at least in part, the persistence of _PfCRT_-76 mutant37,38,39, even if CQ had not been

used in these areas for many years. There are a series of additional factors that may be involved in the presence of phenotypic CQ resistance – such as PfMDR1 mutations40 – that were not

assessed in this study and could lead to an underestimation of the real molecular resistance profile in the area. These factors could be the cause of remaining CQ resistance unrelated to the

presence of _PfCRT_, and should be considered when monitoring molecular resistance in the future. Overall, the encouraging results from this first exploratory trial and molecular analysis

set the scene for subsequent studies to continue exploring the efficacy of CQ in clinical cases with higher parasitaemia, before any final recommendations are made with regards to the use of

this drug in Mozambique. It could be argued that exposing children with clinical malaria to a drug that has only shown partial efficacy to clear infections in semi-immune adults with

low-density, may be hard to justify based on the presented data. Indeed, this population, with allegedly lower levels of acquired immunity to malaria due to their age, may be more vulnerable

to the infection, and at higher risk of responding poorly to a partially effective drug. Thus, as a next step, we aim to continue testing the _in vivo_ efficacy of CQ among adults, but this

time enrolling only those with clinical symptomatology derived from their infections, and higher parasite densities on admission. Only if chloroquine shows good efficacy in this population,

we will deem it possible to start evaluating CQ’s real life efficacy among infected sick children. In the context of malaria elimination, CQ exhibits two conditions that make it attractive

for elimination campaigns: 1) It has been demonstrated to have an excellent safety profile, allowing for its use in all age groups including pregnant women and young children; and 2) Its

relatively long elimination half life (t1/2 = 1–2 months)41 can provide a long post-treatment prophylactic effect. Thus, CQ could be a drug of choice in malaria elimination efforts such as

in MDA campaigns, in combination with a highly effective anti-malarial. It could also be used in similar contexts for those populations who cannot receive ACTs, such as pregnant women in the

first trimester, or very young children, as the safety of CQ in such populations has widely been demonstrated. Finally, through this innovative use of CQ, the drug pressure exerted to the

circulating parasites would be minimal, and risk for re-introduction of resistant mutations would be very low. CONCLUSION This study shows that CQ could play a role, on its own or in

combination with other drugs or tools, as part of malaria elimination efforts at the population level, both on account of its therapeutic efficacy but more importantly by means of its

chemoprophylactic activity and safety profile. REFERENCES * Awasthi, G., Satya Prasad, G. B. & Das, A. Pfcrt haplotypes and the evolutionary history of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium

falciparum. _Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz_ 107, 129–134, doi:10.1590/S0074-02762012000100018 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bruce-Chwatt, L. J. Resistance of P. falciparum

to chloroquine in Africa: true or false? _Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg_ 64, 776–784, doi:10.1016/0035-9203(70)90022-2 (1970). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Harinasuta, T.,

Suntharasamai, P. & Viravan, C. Chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria in Thailand. _Lancet_ 2, 657–660 (1965). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * World Health Organization. WHO

briefing on Malaria Treatment Guidelines and artemisinin monotherapies. Geneva (2006). * Babiker, H. A., Hastings, I. M. & Swedberg, G. Impaired fitness of drug-resistant malaria

parasites: evidence and implication on drug-deployment policies. _Expert review of anti-infective therapy_ 7, 581–593, doi:10.1586/eri.09.29 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Djimde, A. _et al_. A molecular marker for chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria. _N Engl J Med_ 344, 257–263, doi:10.1056/NEJM200101253440403 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Kublin, J. G. _et al_. Reemergence of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum malaria after cessation of chloroquine use in Malawi. _J Infect Dis_ 187, 1870–1875,

doi:10.1086/jid.2003.187.issue-12, doi:JID30387 [pii]10.1086/375419 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mita, T. _et al_. Recovery of chloroquine sensitivity and low prevalence of the

Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter gene mutation K76T following the discontinuance of chloroquine use in Malawi. _The American journal of tropical medicine and

hygiene_ 68, 413–415 (2003). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Takechi, M. _et al_. Therapeutic efficacy of sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine and susceptibility _in vitro_ of P. falciparum isolates to

sulphadoxine-pyremethamine and other antimalarial drugs in Malawian children. _Trop Med Int Health_ 6, 429–434, doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00735.x, doi:tmi735 [pii] (2001). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Frosch, A. E. _et al_. The return of widespread chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum to Malawi. _J Infect Dis_, doi:jiu216 [pii]10.1093/infdis/jiu216 (2014).

* Mwanza, S. _et al_. The return of chloroquine-susceptible Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Zambia. _Malaria journal_ 15, 584, doi:10.1186/s12936-016-1637-3 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Mohammed, A. _et al_. Trends in chloroquine resistance marker, Pfcrt-K76T mutation ten years after chloroquine withdrawal in Tanzania. _Malaria journal_ 12, 415,

doi:10.1186/1475-2875-12-415, doi:1475-2875-12-415[pii]10.1186/1475-2875-12-415 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mwai, L. _et al_. Chloroquine resistance before and

after its withdrawal in Kenya. _Malaria journal_ 8, 106, doi:10.1186/1475-2875-8-106, doi:1475-2875-8-106 [pii]10.1186/1475-2875-8-106 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Laufer, M. K. _et al_. Return of chloroquine antimalarial efficacy in Malawi. _N Engl J Med_ 355, 1959–1966, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa062032, doi:355/19/1959 [pii]10.1056/NEJMoa062032

(2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Laufer, M. K. _et al_. A longitudinal trial comparing chloroquine as monotherapy or in combination with artesunate, azithromycin or

atovaquone-proguanil to treat malaria. _PloS one_ 7, e42284, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042284 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mayor, A. G. _et al_.

Prevalence of the K76T mutation in the putative Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (pfcrt) gene and its relation to chloroquine resistance in Mozambique. _J Infect Dis_

183, 1413–1416, doi:10.1086/jid.2001.183.issue-9, doi:JID001261 [pii]10.1086/319856 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Raman, J. _et al_. Five years of antimalarial resistance

marker surveillance in Gaza Province, Mozambique, following artemisinin-based combination therapy roll out. _PLoS One_ 6, e25992, doi:10.1371/journal.pone, 0025992PONE-D-11-14300 [pii]

(2011). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Thomsen, T. T. _et al_. Rapid selection of Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter gene and multidrug

resistance gene-1 haplotypes associated with past chloroquine and present artemether-lumefantrine use in Inhambane District, southern Mozambique. _The American journal of tropical medicine

and hygiene_ 88, 536–541, doi:10.4269/ajtmh.12-0525 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Abacassamo, F. _et al_. Efficacy of chloroquine, amodiaquine,

sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and combination therapy with artesunate in Mozambican children with non-complicated malaria. _Trop Med Int Health_ 9, 200–208, doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01182.x

(2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * White, N. J. Assessment of the pharmacodynamic properties of antimalarial drugs _in vivo_. _Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy_ 41,

1413–1422 (1997). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Galatas, B. _et al_. A prospective cohort study to assess the micro-epidemiology of Plasmodium falciparum clinical malaria in

Ilha Josina Machel (Manhica, Mozambique). _Malaria journal_ 15, 444, doi:10.1186/s12936-016-1496-y (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tiago, Armindo Daniel, Calú,

Nurbai, Caupers, Paula & Mabunda, Samuel. _Normas de Tratamento da Malária em Moçambique_ (2011). * Planche, T. _et al_. Comparison of methods for the rapid laboratory assessment of

children with malaria. _Am J Trop Med Hyg_ 65, 599–602 (2001). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mayor, A. _et al_. Sub-microscopic infections and long-term recrudescence of Plasmodium

falciparum in Mozambican pregnant women. _Malaria journal_ 8, 9, doi:10.1186/1475-2875-8-9 (2009). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Taylor, S. M. _et al_. A quality control

program within a clinical trial Consortium for PCR protocols to detect Plasmodium species. _Journal of clinical microbiology_ 52, 2144–2149, doi:10.1128/jcm.00565-14 (2014). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * World Health Organization. _Methods and techniques for clinical trials on antimalarial efficacy: genotyping to identify parasite populations_ (2008). *

World Health Organization. WHO. Assessment and monitoring of antimalarial drug efficacy for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization,

http://www.emro.who.int/rbm/publications/protocolwho.pdf (2003). * World Health Organization. _Methods for surveillance of antimalarial drug efficacy_. Available at

http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241597531/en/ (accessed 25/02/2014). (WHO, 2009). * Bretscher, M. T. _et al_. The distribution of Plasmodium falciparum infection durations.

_Epidemics_ 3, 109–118, doi:10.1016/j.epidem.2011.03.002 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Eckhoff, P. Mathematical models of within-host and transmission dynamics to determine

effects of malaria interventions in a variety of transmission settings. _Am J Trop Med Hyg_ 88, 817–827, doi:10.4269/ajtmh.12-0007 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Felger, I. _et al_. The dynamics of natural Plasmodium falciparum infections. _PloS one_ 7, e45542, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045542 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * World Health Organization. _Eliminating malaria_ (2016). * Galatas, B., Bassat, Q. & Mayor, A. Malaria Parasites in the Asymptomatic: Looking for the Hay in the Haystack.

_Trends in parasitology_ 32, 296–308, doi:10.1016/j.pt.2015.11.015 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * White, N. J. The parasite clearance curve. _Malaria journal_ 10, 278,

doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-278 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * World Health Organization. _Methods and techniques for clinical trials on antimalarial drug

efficacy: Genotyping to identify parasite populations_. (WHO, 2008). * Mvumbi, D. M. _et al_. Assessment of pfcrt 72–76 haplotypes eight years after chloroquine withdrawal in Kinshasa,

Democratic Republic of Congo. _Malaria journal_ 12, 459, doi:10.1186/1475-2875-12-459 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cortese, J. F., Caraballo, A., Contreras, C.

E. & Plowe, C. V. Origin and dissemination of Plasmodium falciparum drug-resistance mutations in South America. _J Infect Dis_ 186, 999–1006, doi:10.1086/jid.2002.186.issue-7,

doi:JID020423 [pii] 10.1086/342946 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Vieira, P. P., das Gracas Alecrim, M., da Silva, L. H., Gonzalez-Jimenez, I. & Zalis, M. G. Analysis of

the PfCRT K76T mutation in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the Amazon region of Brazil. _J Infect Dis_ 183, 1832–1833, doi:10.1086/jid.2001.183.issue-12, doi:JID010159[pii]

10.1086/320739 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zalis, M. G., Pang, L., Silveira, M. S., Milhous, W. K. & Wirth, D. F. Characterization of Plasmodium falciparum isolated

from the Amazon region of Brazil: evidence for quinine resistance. _The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene_ 58, 630–637 (1998). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Volkman, S. K.,

Cowman, A. F. & Wirth, D. F. Functional complementation of the ste6 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum. _Proceedings of the National Academy

of Sciences of the United States of America_ 92, 8921–8925, doi:10.1073/pnas.92.19.8921 (1995). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nosten, F. & White, N. J.

Artemisinin-based combination treatment of falciparum malaria. _Am J Trop Med Hyg_ 77, 181–192 (2007). CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to

thank all the study participants for their collaboration. We would also like to thank the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for providing the funds for this study. Finally, we thank everyone

who supported this study directly or indirectly through fieldwork, clinical, laboratory or analysis support. QB is an ICREA (Institut Català de la Recerca i Estudis Avançats; Catalan

Government) Research Professor. AM has a CES10/021-I3SNS fellowship. ISGlobal is a member of the CERCA Programme, Generalitat de Catalunya. This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda

Gates Foundation, as part of a Malaria Elimination grant to CISM. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Quique Bassat and Pedro Aide contributed equally to this work. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS *

Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça (CISM), Maputo, Mozambique Beatriz Galatas, Lidia Nhamussua, Lurdes Mabote, Clara Menéndez, Eusebio Macete, Francisco Saute, Alfredo Mayor, Pedro

Alonso, Quique Bassat & Pedro Aide * ISGlobal, Barcelona Ctr. Int. Health Res. (CRESIB), Hospital Clínic - Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Beatriz Galatas, Pau Cisteró,

Himanshu Gupta, Regina Rabinovich, Clara Menéndez, Alfredo Mayor, Pedro Alonso & Quique Bassat * National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP), Ministry of Health, Maputo, Mozambique

Baltazar Candrinho * National Directorate of Health, Ministry of Health, Maputo, Mozambique Eusebio Macete & Pedro Aide * ICREA, Pg. Lluís Companys 23, 08010, Barcelona, Spain Quique

Bassat Authors * Beatriz Galatas View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lidia Nhamussua View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Baltazar Candrinho View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lurdes Mabote View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Pau Cisteró View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Himanshu Gupta View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Regina Rabinovich View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Clara Menéndez View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Eusebio Macete View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Francisco Saute View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alfredo Mayor View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Pedro Alonso View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Quique Bassat View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Pedro Aide View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS B.G.: participated in the study design and

fieldwork, conducted the data analysis and wrote the draft of this manuscript. L.N.: lead fieldwork activities and data cleaning process, and participated in the analysis and writing of this

article. B.C.: participated in the study design, interpretation of results and writing of this article. L.M.: assisted in fieldwork activities and data cleaning. P.C.: Participated in

laboratory analyses. H.G.: Participated in laboratory analyses. R.R.: participated in the study design, interpretation of results and writing of this article. C.M.: participated in the study

design, interpretation of results and writing of this article. F.S.: participated in the study design, interpretation of results and writing of this article. E.M.: participated in the study

design, interpretation of results and writing of this article. A.M.: participated in the study design, in study analyses, in the interpretation of results and writing of this article. P.A.:

Conceived the study, participated in interpretation of results and writing of this article. Q.B.: participated in the study design and supervised all fieldwork and laboratory activities,

data cleaning and analysis, and writing of this article. P.A.: participated in the study design and supervised all fieldwork and laboratory activities, data cleaning and analysis, and

writing of this article. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Quique Bassat. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare that they have no competing interests. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as

long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Galatas, B., Nhamussua, L.,

Candrinho, B. _et al._ _In-Vivo_ Efficacy of Chloroquine to Clear Asymptomatic Infections in Mozambican Adults: A Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial with Implications for Elimination

Strategies. _Sci Rep_ 7, 1356 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01365-4 Download citation * Received: 04 November 2016 * Accepted: 29 March 2017 * Published: 02 May 2017 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01365-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative